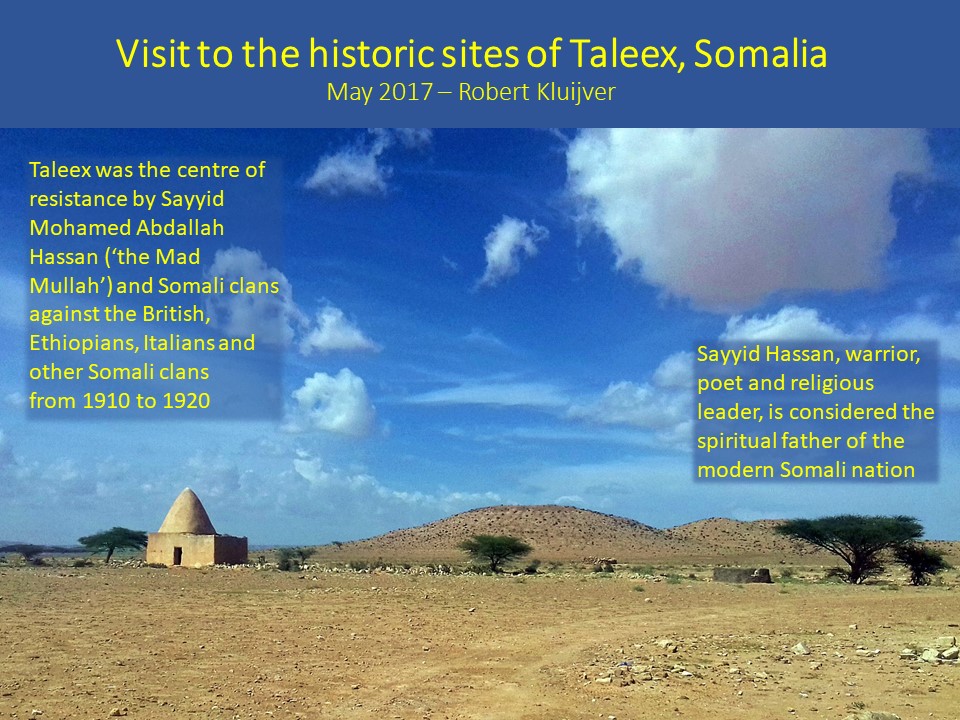

Over the past year I spent a lot of time researching contemporary Somali culture in the Horn of Africa (Somalia, Somaliland, Somali Regional State in Ethiopia, Addis, Nairobi, North-Eastern Provinces of Kenya) for the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and a nice little consulting outfit focusing on culture called Aleph Strategies.

Unusually, SDC is planning a 12-year long smart investment into the development of Somali culture, and this report is the baseline study allowing to build a strategy. Donors rarely have the long-term perspective which allows for slow and steady build-up: the contrary of so-called ‘Quick Impact Projects’.

As part of their strategy, SDC agreed that we could prepare and disseminate a public version of the report. It covers the different types of cultural expression, the social and political context of cultural production in each region and it gives examples of current cultural developments and groups.

Here’s a link to the report