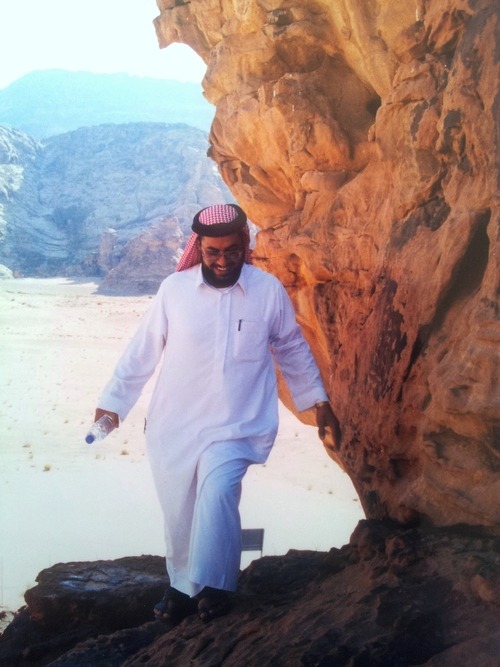

Photo taken in the ruins of the city of Al Ukhdood (ancient Najran) by Abdelkarim Qassem

One of the premises of the ‘Searching for Ancient Arabia’ research project is the cultural diversity of the Arabian Peninsula; one of the research hypotheses being that this pluralism—well evident in ancient history—was smothered by subsequent narratives and historical developments, but that it could be a great asset for the future development of the Gulf region, particularly in artistic and cultural terms.

My previous blog post explored the role cultural heritage plays in Bahrain. I would now like to turn to the complex issue of cultural heritage in Saudi Arabia. My next blog post will examine the case of the UAE.

Ancient Dam at Khaybar, 150 km north of Medina. Khaybar was a wealthy Jewish settlement until the Jews were expelled by Caliph Umar. The dams ensured agricultural prosperity. Photo by my father, M. Kluijver.

Najran

My interest in Najran was awoken by an as yet unpublished experimental artwork by the Saudi artist Abdulnasser Gharem. It reminded me of a trip I had made in my childhood, when my father was working in the country, to the region, and I resolved to return there as soon as I had the opportunity. That was provided to me by the fellowship I received for this research from NYU Abu Dhabi’s FIND programme.

Najran is a dusty town in southern Saudi Arabia, a few kilometers north of the Yemeni border. It is not a place many foreigners go to; and of the visitors that do come, only few visit the site of Al Ukhdood, a major city from the pre-Islamic period that has been almost wholly excavated.

Main thoroughfare of Al Ukhdood, with monumental buildings on either side and the mountains of Yemen in the background. Photo by R. Kluijver.

This is surprising: not only because of the quality of the site (the excavated city is large at 220 by 235 meters, its architecture is compellingly visible and there are fascinating rock engravings on many of the stone blocks used in its construction), but also because the city features prominently in the Holy Quran, as a place of damnation where a massacre took place a century before the Hegira[1].

The beautiful square cuts of the masonry at Al Ukhdood are proof of an advanced culture, as are the well-executed inscriptions. Photo by R. Kluijver.

One could therefore expect detailed descriptions and analyses online, and a steady inflow of Saudi and other Muslim tourists, in the same way the biblical sites in Palestine attract Christian tourists. But no! We were the only visitors for most of the day. Even educated people from the nearby town admitted never having been there before.

In fact, the site is officially closed, but a security guard speaking on his phone in the shade of his pickup suggested with a gesture that we should enter through a hole in the fence. The site museum, which used to be unimpressive, is being renovated into a big visitor center, so maybe the provincial government expects more visitors, but, just as likely, this is a prestige project without a real audience in mind.

Descriptions of the site are hard to find online (see here for a summary report with photographs by an American tourist, and here for a more detailed but still insufficient description by a local tour operator). As to me, I have neither the required knowledge, nor the intention, to provide a detailed scientific analysis of the site. What I can say, however, is that this is one of the most impressive archaeological sites I have ever seen[2]. This makes one wonder why there is so little public interest in cultural heritage in Saudi Arabia

Saudi attitudes towards cultural heritage

Saudi Arabian cultural heritage policies are quite contradictory. On the one hand, there has beena rapid destruction of cultural heritage, including many early Islamic monuments such as the birthplace of the prophet Muhammad (replaced by public toilets), and mosques and mausoleums built by or for the companions of the prophet. The arguments given for this destruction range from the practical (infrastructural works) to the religious (preventing shirk or polytheism, assuming the admiration of cultural heritage could detract believers from the worship of the one God). For more information see this page of related Saudi fatwas, or the opinions on this matter of Saudi specialists such as Dr. Sami Angawi or Anwar Eshki, as compiled in, for example, this comprehensive article on the destruction of Islamic heritage in the Kingdom.

This funerary monument, found near Ha’il, is about 6000 years old. Note the double-bladed sword. Photo from the ‘Roads of Arabia’ website.

On the other hand, Saudi Arabia not only allows, but also at times encourages archaeological exploration by foreign scholars. It has lavishly funded the ‘Roads of Arabia’ exhibition about pre-Islamic Saudi history organized by the Louvre, as well as the Hajj exhibition first hosted by the British Museum. Both exhibitions traveled to other locations with Saudi support. This encouraging attitude towards cultural heritage is not only for foreign consumption; the collection of the National Museum in Riyadh and its display are up to international standards.

The ruling Emir of Ha’il, an archaeology buff, in the 1990s. Photo by my father, Marinus Kluijver

The ruling elites of the country can also be great lovers of their country and its history. The photograph above depicts the Emir of Ha’il touring my father around the province’s many sites with rock engravings, back in the 1990s. The governors of Makkah and Medina provinces both have recently stood up, against further attacks on their city’s cultural heritage.

The preservation of cultural heritage has become the responsibility of a few wealthy educated Saudis. The architect Dr. Sami Angawi built his house in Jeddah incorporating many different Saudi crafts and building traditions. Photo by R. Kluijver

As with other policies dealing with society and culture in Saudi Arabia, their dual, ambiguous nature does not seem to be a temporary contradiction. It rather seems enshrined in the very constitutional make-up of the Kingdom: the pact between the Wahhabi clergy and the House of Al Saud, whereby the former is allowed to rule society on the condition of explicit obedience to the royal family, which manages the destiny of the country.

Indeed, the National Museum of Riyadh offers a beautiful example of this contradiction. When leaving the pre-Islamic galleries on the ground floor, the visitor must pass through a sound and light display in a small corridor, where he/she learns that all the magnificent cultural artifacts, architectural grandeur and scientific explanations that he/she has just seen are nothing else than evidence of the ignorance (jahiliyya) which characterized the pre-Islamic period. After this ordeal, the visitor emerges in a great hall basking in light. On one side is a monumental entrance that can be used to circumvent the ground floor displays, in front of which an endless escalator leads to the spacious first floor, dedicated to the Islamic history of the country. One surmises that members of the clergy and their followers use this entrance to avoid being confronted with the ‘polytheistic’ past of the Kingdom.

Contemporary Historic Dissonances

The most interesting part of my visit to Najran was the road trip from Abha. I spent some days enjoying the hospitality of Ibrahim Abumsmar, a contemporary artist, working with him on his next solo. His family hails from Rijal al Alma, a village hanging off a cliff in the magnificent green escarpment bordering Abha towards the Red Sea[3], and he has spent most of his life in Abha.

Ibrahim and his friend, the artist Abdelkarim Qassem, proved knowledgeable guides about the Asir, the province of which Abha is the capital. This region historically enjoyed considerable autonomy, and was as close to Yemen as to other neighboring regions until the Saudis took over, after a brief war, and annexed the province into the Kingdom in 1934, barely 80 years ago. It is one of the few areas on the Arabian Peninsula that catches enough rain for subsistence agriculture, and it has a sedentary society as a result.

Ibrahim Abumsmar guiding through the ruins of what was purportedly the first public school in the Asir, built in the 1950s. Photo by R. Kluijver.

As we drove south-east through this mountainous region, Ibrahim and Abdelkarim pointed out the many changes that had occurred in the province and its society over the past years. Since the 1980s, in particular, change planned by the central government has been rapid. This not only affects the landscapes (rapid urbanization, destruction of traditional habitats) but also the people living in it. Old men still remember the days that Christian and Jewish merchants would come to the local markets. They have been replaced by shops staffed by South Asians, selling Chinese and other global produce. Crops cherished by the Asiris are no longer planted, and the small holdings set on rain-fed terraces along the mountainsides have been replaced by larger, industrialized farms in the flat (and dry) lands that guzzle up groundwater at an alarming rate.

Example of a traditional Asiri house, now abandoned in favor of more contemporary – but not necessarily more comfortable – lifestyles. Photo by R. Kluijver.

But besides these changes that inevitably seem to accompany modernity, there has also been a conscious effort to align Asiri society with what one might call Nejdi[4] values: a stricter observance of social propriety rules and more fundamentalist religious practices. Thirty years ago, people in the villages used to dance together at the harvest – men and women, old and young together. Now young men will not show their wife’s face to their own brothers, and mothers will not let their sons pronounce their names in public. Local society seems to have assimilated these new values very easily. In turn local artists and intellectuals wonder what has happened to their culture, and where it is going.

Obviously, the Saudi government also has a strong incentive to shield its Southwestern provinces from the unrest that has plagued Yemen over the past decade. In 2009, a six-month war took place between the Saudi Army and Houthi rebels from northern Yemen, who used to traverse the porous border easily (it has now become difficult). The artist Abdelkarim Qassem portrays a gripping moment from this war in his video ‘Evacuation’. But local culture also suffers as a result. The Zaydi faith that inspires the Houthi rebels is shared by a majority of the population in Najran[5]. Although the tribal loyalty of the main tribe of Najran (the Yam) to the Al Saud remains unquestioned since the 1930s, their protests against religious persecution have been met withviolence. (Human Rights Watch published a report on the issue in 2008). Similarly, many Asiris resent being cut off from their Yemeni neighbors, with whom they used to entertain close commercial and cultural relations.

It thus dawned on me that the dynamics between Ancient Arabia and contemporary culture, which this research focuses on, are still at play in the contemporary period – as recollections of how the country used to be fifty years ago and now. This makes the role of artists in expressing and negotiating cultural change all the more pressing. Asiri artists, such as Ahmed Mater and those mentioned above, take this role seriously, infusing the contemporary art world in Saudi Arabia with much of its vibrancy. One wonders what may happen when artists and intellectuals reach back to the potent symbols and rich cultures of Ancient Arabia to develop a vision of a society with a strong potential rooted in Arabian cultural diversity.

Emara Castle in Najran, built in 1944 (and photographed by Thesiger in 1947) is a rare example of preserved traditional architecture. Photo by R. Kluijver.

[1] Surah 85 (Al Buruj, known as ‘The Constellations’ in English): “Perish the People of the Trench / With its fire and its faggots / As they sat above it / Witnessing what they did to the faithful / All they held against them was their belief in God (…). Translation by Tarif Khalidi, Penguin Books 2008. While this passage may also refer to other historic events, the most commonly accepted explanation is that it refers to the massacre of Christians by Jewish converts in Al Ukhdood near Najran.

[2] A selection of Wikipedia pages providing interesting backgrounds:

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_community_of_Najran

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Jews_in_Saudi_Arabia

[3] Rijal al Alma is also the native village of the contemporary artists Ahmed Mater and Abdelkarim Qassem. This group, with their friends, has played an important part in the genesis of the contemporary Saudi art movement.

[4] From the Nejd, the central desert region from which the Al Saud family hails, and whose capital is Riyadh.

[5] This faith is often branded as Isma’ilism by foreign experts, but the local population rejects this association. They recognize their faith as a branch of Shiism, but unrelated to that practiced in Iran or elsewhere.