Note: a very different, one-page graphic version of this article was published in the Belgian art magazine A Prior #23; see the article here. I published another article about this subject in the Indian art magazine Take On Art.

With fourteen Afghan artists and at least ten artists whose work reflects on this country, Documenta 13 is strongly flavored by Afghanistan. After Kassel, Kabul is the main location of Documenta (the others being Alexandria & Cairo, and Banff in Canada): 27 Documenta artists will show their work in the Queen’s Palace in Kabul’s Babur Gardens in an exhibition that opens on June 20.

Why this focus on Afghanistan? Over the past few years we have become accustomed to the celebration in biennials of ‘emerging’ art scenes in non-Western countries. There is however no Afghan art boom; after the appearance of Lida Abdul at the Venice Biennial in 2005 and a small presence at the East-West Diwan during the Venice Biennial of 2009, the Afghan art scene remained suspiciously quiet.

The reason for Afghanistan’s presence here is rather personal than a strategic curatorial choice. This Documenta is full of rare narratives that go ‘against the grain’ of official narratives. One of those is the story of Alighiero Boetti’s hotel in Kabul. This Italian artist, associated with Arte Povera, partially lived and worked in Kabul between 1971 and 1977, where he opened a hotel called ‘One Hotel’. The artist Mario Garcia Torres was inspired by this detail of art history and conducted a partially fictional research to find this hotel from 2001 onwards. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the curator of Documenta 13, knew about this research, decided to include it, then traveled to Kabul in 2010 and became fascinated by the country. She decided to organize a manifestation of the Documenta in Kabul – with seminars by Afghan and international artists and a big exhibition – and commissioned some of the international artists to create a work for it.

The key piece is Alighiero Boetti’s ‘World Map’, a carpet showing a world map with each country’s flag (see wall text here). It was produced for Szeeman’s legendary Documenta of 1972, but ultimately the artist decided to show another work instead. After 40 years the Map finally hangs in the Fridericianum, surrounded by Mario Garcia Torres’ research project, which consists of fictional faxes he sent to the deceased artist in 2001, as if he were roaming the streets of Kabul in search of the hotel, a documentary he made in Kabul when he finally went there in 2010, and a film about his quest. Garcia Torres finally found the hotel, then rented, renovated and partially reopened it, trying to make it into a hub of artistic activity.

In the Fridericianum’s Rotunda, the ‘brain’ of the Documenta – the collection of artworks and objects that inspired the rest of the exhibition – we find statues of Bactrian princesses that were found in the area encompassing Northern Afghanistan, Tajikistan and South Uzbekistan as well as an oil painting by the veteran Afghan artist Mohammed Yusuf Asefi. The Bactrian statuettes, dating from around 2000 BC, are extremely beautiful stylized figures that recall that this area was once a cradle of civilizations. As to Asefi, he is among the most talented of Afghanistan’s older generation of painters; he also played an important role by staying in Afghanistan during the Taliban rule and painting over human figures in the National Gallery’s oil paintings with water colors, so that the Taliban wouldn’t take offense and destroy the paintings in their iconoclastic rage. After the fall of the Taliban he removed the water colors with a sponge to restore the original paintings.

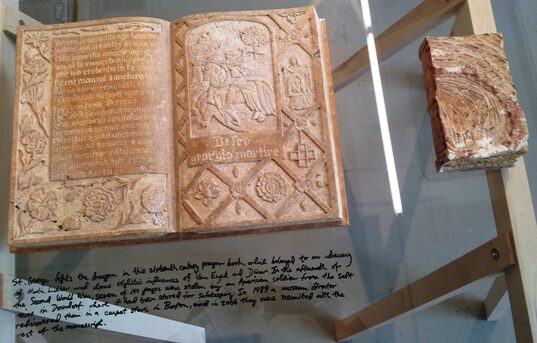

Of the other artworks in the Fridericianum related to Afghanistan, Michael Rakowitz’s is the most profound. Rakowitz travelled to Bamiyan, the site in central Afghanistan where the Taliban destroyed the famous Buddhas, and conducted a stone-carving workshop with local craftsmen. The results of that workshop will mainly be shown in Kabul (a few pieces are part of the installation in Kassel). In his archive-like installation in Kassel the artist relates the destruction of the Buddhas to the burning of the library of the Fridericianum during the Allied bombing of the city in 1941, with the loss of many rare manuscripts as a result. Stone carvers from Carrara carved some of the lost books in marble and in Bamiyan’s sandstone, which the artist managed to get to Europe.

The stone books are like tombstones on the one hand; on the other they refer to the tradition in Europe of stone bibles for the illiterate, which again leads the installation towards Afghanistan and the illiterate craftsmen Rakowitz was working with. As usual the artist branches off into several related sub-topics, such as the rubble from the Nazi’s bombing of London which was strewn from RAF bomber planes over German cities as a prelude to the bombs that were to follow (see wall text here).

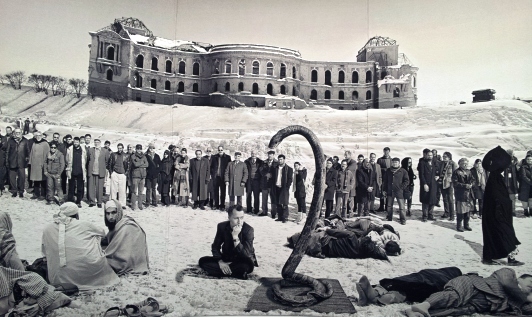

The Polish artist Goshka Macuga brings Kabul to the Fridericianum on a huge 17 x 5 meter carpet that shows the whole arts & culture community of Kabul standing against a backdrop of the Darulaman parliament building, which was destroyed during the civil war and has never been repaired. In the group portrait that serves as the original for the carpet, which was produced in Belgium, she inserts extraneous elements like Afghans sleeping on the ground or a dancing cobra, and of course a burqa-clad woman carrying a bundle on her head.

The relation between the shelled Darulaman building and the Fridericianum is also made by Mariam Ghani, who superposes images of both as the camera travels through the buildings, with her reflections and musings as a soundtrack.

The other Afghan artists are mostly brought together in the Elisabeth Hospital just behind the Fridericianum. Here we find some of the Afghans that are considered young talents, such as Jeanno Gaussi, Masood Kamandy, Qassem Foushanji, Mohsen Taasha and Zainab Haidary, as well as the more established artists Zalmai Ahad, Rahraw Omarzad and of course Lida Abdul. The results of the Afghan seminars by Barmak Akram, the Mumbai-based collective CAMP and Mariam Ghani are also shown here.

This group exhibition certainly transmits the liveliness of the Documenta team’s involvement with Afghanistan; but the quality of the work of the Afghan artists is not convincing – the two pictures above show what I found most interesting. And here we run into the problems and limitations inherent in Christov-Bakargiev’s approach. The problem is that thus far no good contemporary visual art is being made in Afghanistan, according to the standards of the Documenta. And the limitations are caused by the fact that she ended up relying heavily on the US-Afghan connection. Mariam Ghani, Lida Abdul and Aman Mojadidi (the latter is represented at Documenta with a sound & book installation in the Weinberg Bunker) grew up in the USA and came to know Afghanistan after 2001. Aman has developed new roots in Afghanistan; he will curate the Documenta Kabul exhibition and has done a lot to help young Afghan artists; but the other two artists have only briefly sojourned in Afghanistan. The same can be said of many other Afghan artists that are known internationally, and some of whom are prominent in the Documenta. This of course doesn’t detract from their quality as artists. But how tuned-in are they to contemporary developments in Afghanistan? Their relationship with this country is colored by their dreams of a homeland that would conform to their expectations, which are in turn shaped by the nostalgia of their exiled parents. Their art reflects this and, in my experience, doesn’t resonate much with Afghans that didn’t grow up abroad.

In the Elisabeth Hospital one can look through the results of the Documenta seminars held in Kabul and Bamiyan. Some of them produced tangible and interesting results, such as the joint workshop by CAMP/Pad.ma and Mariam Ghani who digitized some of Afghan Films collection and put it online. But one may wonder what the output was from most other seminars and lectures held in this series. I have sat through many of them during my time in Kabul, and found that most did not manage to bridge the gulf between the realities of the international art world and that of Afghan practicioners. Surprisingly several of the volumes of transcripts I flipped through at Documenta were completely blank. This may be a misprint, but it could also be a reflection of what these seminars actually left in terms of true exchange.

Results of Barmak Akram’s ceramics workshop on improvisation with Afghan art students in the potters’ village of Istalif

An extreme example may be the workshop on improvisation in ceramics given by the Paris-based artist Barmak Akram to Afghan artists at the potters’ vilage of Istalif. I sympathize with Barmak’s effort to free the Afghan artists from their obsession with perfect form and predictable results. But what how will this gesture be received in Afghanistan? I spent quite a lot of time in Istalif and came to know the potters well. I do not think they will be very impressed by the results of the students’ improvisation so I doubt any form of dialogue was created with the potters. There is a danger of cultural arrogance here, and Afghans are very sensitive about this; especially when it comes from Afghans who returned from abroad after the fall of the Taliban.

With the exception of Aman Mojadidi all the mediators of the Afghan art world that appear at international events are foreign-based and –raised Afghans, most of whom hardly spent time in Afghanistan. They have risen to prominence because of the enormous demand in the international art world for Afghan contemporary art in all formats: street art, documentary photography, film, miniature painting – whatever. At times it seems as if any Afghan willing to pick up a spray-paint can or camera, and who has the chance to meet a curator or other art professional that visits Kabul (each of these visitors typically thinks he/she is the first one to embark on such an adventure), may find himself at a Biennial or the Documenta a few months later.

As one of the Afghan mediators confided to me, the young Afghan artists shown here and in other exhibitions abroad won’t even attempt to make art if there’s no international funding available. This is not entirely true, as I know enough Afghan artists who never connected to the international scene and are making art nonetheless. But their artistic production is not yet of sufficient level to include in an international exhibition. In the one exhibition I attempted (see here) I decided to focus on the rapidly evolving contemporary Afghan culture instead of on the arts and included advertising, TV productions and carpet designs next to contemporary artistic expressions.

The problem here is not that Afghan arts need to be developed from scratch: this offers exciting opportunities. Afghans are creative and strong-willed and they do like to express their personal opinions, so they could make good artists. The problem is that Afghan arts are not given sufficient time to develop on their own (with measured, wise input from abroad according to the needs and requirements expressed by the Afghan practicioners). How can a young artist develop when his very first works are shown in Documenta or the Venice Biennial, or are celebrated on CNN? (One of my students wrote a paper about such a media darling artist, Shamsia Hassani: find it here). How does this affect the expectations of other young artists? What about the older artists, or the young artists who are not connected to one of the Afghan mediators and thus don’t meet the curators and foreign artists alighting briefly in Afghanistan to discover young talents and impart their knowledge in a workshop? For any person truly committed to developing the Afghan art scene as part of the broader cultural development in the country, this international eagerness is rather disruptive than constructive.

There is no arts infrastructure in Afghanistan. No galleries, no art museums, no proper art education, no curators, no art critics, no collectors, no media devoted to art. Some of these elements would need to be in place before one could speak of an Afghan art scene. But as long as there are shortcuts directly linking fledgling artists to the international art world there is no incentive to develop this infrastructure.

The international arts community should be patient, and wait for Afghan artists to start manifesting themselves; and then hold them to the same critical standards as, say, artists from Pakistan and Iran. This Documenta, for all its sympathetic enthusiasm towards Afghanistan, fails to do that, and thus, in my opinion, does not do Afghan arts a service.

Nonetheless I really enjoyed this Documenta, and thought it was overall full of good and highly interesting art.

Robert,

As always, very interesting and defining a clear and courageous point of view. It is true that the West is interested in quick result and fast solution. Not only in regard to art, but politically with the transformation to a democracy, socially, economically and even militarily. “Time is money” is the modus operandi in the US or EU, but how can time be measured in Afghanistan, where war, occupation and destruction has been going on since 1979. 33 years of uninterrupted war is a very long time, where everything is still working and moving forward, but almost as a parallel life, with this relentless notion of a “real life” without war to arrive one day. Multiple generations have been living in refugee camps for over 30 years, waiting for the situation to stabilize. Maybe these parallel and unreconcilable universes of an idealized world-with-no-war juxtaposed with the struggle of a tough everyday life make Afghan contemporary art quite interesting and productive. Nevertheless, these parallel universe are interesting only because there is such an extended period of latent potential, of waiting without having time to wait. But if this tension is the actual strength underlying the work of the contemporary Afghan art, trying to simplify its production and dissemination through shortcuts and quick success stories is not going to help it mature. Except if it is done with a critical understanding of the Western concept of temporality contrasted with the Afghan concept of temporality.

Hello Robert,

Thank you for this excellent essay. I’m working on a publication on dOCUMENTA and would love to speak more with you about this. Please feel free to be in touch with me via email: bitsy.knox@gmail.com.

Many thanks,

BK