These are two projects I worked on with Gilles Stassart when in Ethiopia; they finally blended into one at the Alliance Éthio-Française in Addis Ababa, in a series of performances:

- VIP dinner with WFP rations, November 2018

- Sonic Barbecue part 1, November 2018

- Sonic Barbecue part 2, March 2019

Part 1: The Hunger Kitchen

The Hunger Kitchen idea started with the following observation that I made while working in Somaliland and Somalia: beneficiaries of food aid generally dislike the food rations they receive, and do not know what to do with them. Therefore, they often resell those rations to buy foodstuffs they’re more familiar with.

My friend Gilles Stassart, an experimental cook who has worked in many different places in the world, suggested we approach the World Food Program (WFP) and NGOs to suggest a cooking workshop for refugees. In these workshops we’d explore with them how to cook the rations in ways that fall within their own culinary traditions or aspirations, adding only cheap, simple ingredients found everywhere like onions, eggs and wheat flour. We selected several places in Somaliland where we could provide such workshops and approached the WFP and NGOs working in food distribution for their cooperation and financial support.

We soon found out that matters such as the non-acceptance of food aid by beneficiaries, and the resale of aid on the markets are taboo subjects for WFP. One recently appointed manager reacted enthusiastically and supported us initially, but halfway through the project he stopped responding to our emails; he must have received a warning from his bosses. With his assistance, however, we obtained a full set of food rations for refugees, with which we started experimenting. But we never received funding or the green light to continue. NGOs, who receive a sizable income from distributing WFP rations, similarly failed to cooperate, despite what were often enthusiastic initial reactions.

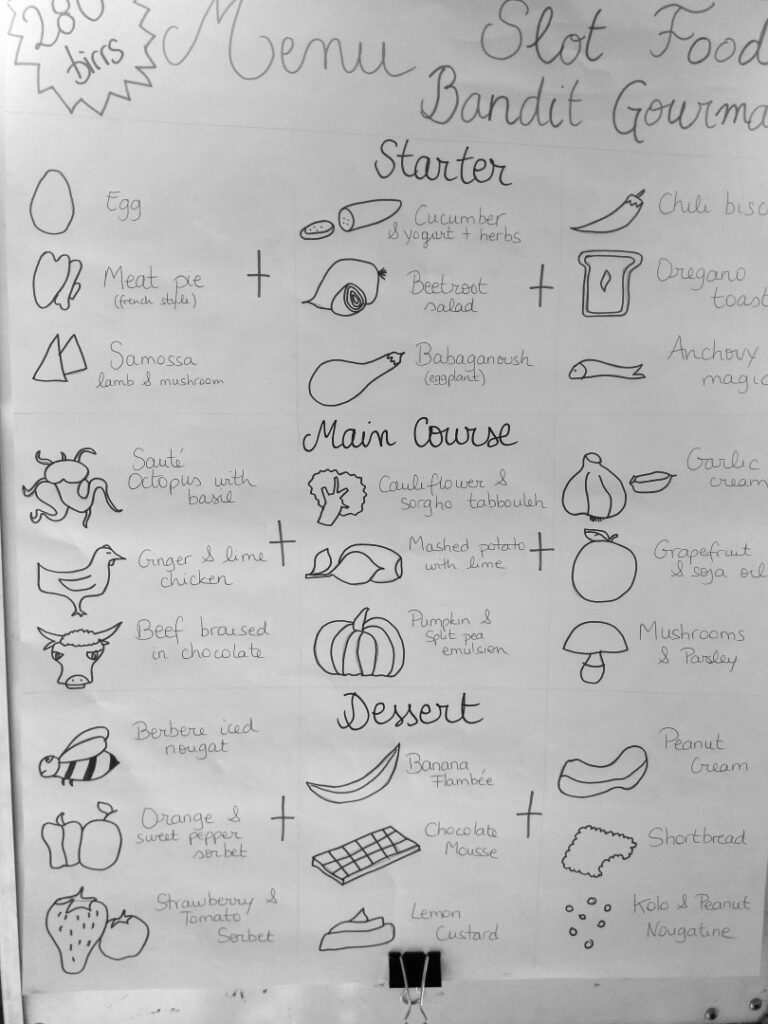

Meanwhile the Alliance Éthio-Française had asked Gilles to organise a VIP dinner to celebrate the re-opening of the restaurant in their beautiful cultural centre, in the heart of Addis Ababa. We decided to surprise the guests by serving them a dinner made with only WFP rations. The food the VIPs reserve for the poor refugees would be used to cook a dinner for them. By now you may wonder what WFP rations are. A standard ration, per person per month, consists of the following:

- 13,5 kg cereals

- 1,5 kg pulses

- 1,5 kg CSB++

- 0,9 kg vegetable oil

- 0,15 kg salt

According to the WFP website, it distributed 7 million rations a month in Ethiopia in May 2017.

CSB++ stands for Corn Soya Base enriched with sugar and milk powder; it is meant to be eaten as a porridge. The cereals we received were whole-grain red sorghum, and the pulses were split yellow peas. The vegetable oil is Palmolein (filtered Palm Oil). In addition, the WFP, UNICEF and NGOs often distribute ‘plumpy nut’, especially to malnourished children. This is peanut butter enriched with vitamins and minerals, and very sweet.

Honestly, we were quite disgusted by the quality of the rations and could easily understand why Somalis and Ethiopians, used to fresh, wholesome local produce, would find it hard to eat this stuff. The sorghum and pulses were full of dirt and a bit stale. With the CSB++ Gilles scratched his head… how was he going to use this for tasty cooking? As to the plumpy nut, it had a strange, chemical taste.

We started experimenting with these ingredients, and Gilles came up with the following: he found out that by frying the sorghum in the palm oil, it popped; with a bit of salt, it made quite nice popcorn. Of course this may not be very healthy, but it is aspirational as people everywhere, also many of those in refugee camps, know about popcorn and like it. In the Ethiopian highlands popcorn is traditionally eaten during the coffee ceremony.

Next we cooked the yellow split peas al dente, and then mashed it with a fork. We mixed it with onions fried in the palm oil, egg yolk and salt, and then made balls with the result, covered them in flour and cooked them in the palm oil, producing something resembling falafel. With a bit of beef stock, we found the same mix could be cooked to resemble a hamburger – again, highly aspirational food. We imagined that WFP rations could thus be used to allow entrepreneurial refugees to set up food stands, offering popcorn, ‘falafel’ and ‘hamburgers’. But the WFP doesn’t allow what it calls ‘commercialisation’ of its food aid.

We were still left with the enriched Corn-Soya Base and the plumpy-nut. We decided to make pancakes out of those; first we made stodgy porridge with the consistency of polenta, mixing the CSB++ with hot water and a pinch of salt; then we mixed it with the plumpy-nut, added eggs and lightly fried them in the palm oil. They were surprisingly sweet.

When the VIPs, including the French and Canadian ambassadors and several high-ranking people from the Ethiopian government, were seated we surprised them by serving, first, a large plate each containing only a few seeds of sorghum popcorn (we didn’t want to ruin their appetite). Then I explained the Hunger Kitchen project to them, and we served the ‘falafel’ and ‘pancakes’. They found it … interesting…. but were very relieved when they found out, after having tasted everything, that Gilles had cooked a proper five-course dinner for them.

Unfortunately, this performance did not persuade any of the VIPs to support our Hunger Kitchen project. We experienced, once again, how the make-believe world we live in, where poor starving Africans look gratefully upon the rich white man who gives them free food, is irreconcilably opposed to the real world, where sub-standard Western agricultural surpluses are dumped on African markets along with chemical compounds full of sugar; in the process ruining local agricultural markets by driving down prices.

On the latter point, I recall something I realised when I was chief analyst for an NGO information platform working in Somalia. In 2017, as nearly every year, the UN raised a humanitarian appeal to combat a supposedly pending famine because of drought in Somalia. Using terrifying statistics of possible victims, the UN raised a billion dollars, which corresponds to three times the annual budget of the Somali government. Besides vamping up its own operations and those of NGOs, the UN/WFP organised large shipments of food aid.

However, many of the areas hardest hit by the drought are under control of Al Shabaab. They cannot receive aid as that aid would be seen as terrorist financing under the international ‘Counter Terrorism Financing’ regulations. The reasoning is that local authorities profit doubly from food aid, by relieving them of the requirement to spend money to help the population (so they can spend more on, for example, the war effort) and because they always manage to extract some benefit directly from humanitarian operations, for example by providing security or forcing them to buy operating licenses. So people living in areas controlled by the enemies of the West are effectively barred from receiving aid.

But in 2017, as in other years since 2012, there was luckily no famine. The UN congratulated itself on a successful operation but there were also no famine-deaths reported in Al Shabaab areas. So either Al Shabaab mounted a humanitarian operation as effective as the UN, or there was no famine situation. By traveling extensively through the country, I can ascertain it was the latter. Yes, people were affected by the drought but no, they were not dying as they have other coping mechanisms, and access to aid is but one of these.

In fact the Somali population, which mostly lives from the agricultural sector (livestock and crops) is negatively affected by free food aid which drives down prices for their produce, to a point where it makes no sense any longer to plant crops – because every year the UN raises another appeal to help the poor Somalis threatened by famine, disease or other hardships.

Who benefits from the billion dollars food aid? Well, everybody except the taxpayers on one end and the so-called beneficiaries on the other. US and Western subsidized farmers, the subsidy lobbies, the agro-pharma-industry which creates and markets products like plumpy nut and CSB++, shipping companies, the UN itself and all the NGOs and consultants paid from that money, the national and local authorities and business communities, and even media which sell sensational stories about famine and ‘positive news’ about humanitarian charity. Most of these organisations take a cut from that billion.

Part 2: Sonic Barbecue and the Slot-Food Machine

text to be added later

Part 3: Sonic Barbecue part 2 with Faizal Mostrixx

text to be added later