Over the past years, most of my visits to contemporary art exhibitions have ended in disappointment. I consider myself an ex-curator: after my last show in 2015 I decided to step out of the art world. I usually tell people I enjoyed working with artists but increasingly disliked the art world, in both its commercial and institutional aspects. But this Biennale has left me inspired and hopeful for the art world – reviving my old hope that artists give creative expression to the deep undercurrents of collective development, giving an indication of where we are heading. This impression was left especially by “The Milk of Dreams” show curated by Cecilia Alemani, but surprisingly also by many of the national pavilions and some of the collateral events.

The experience

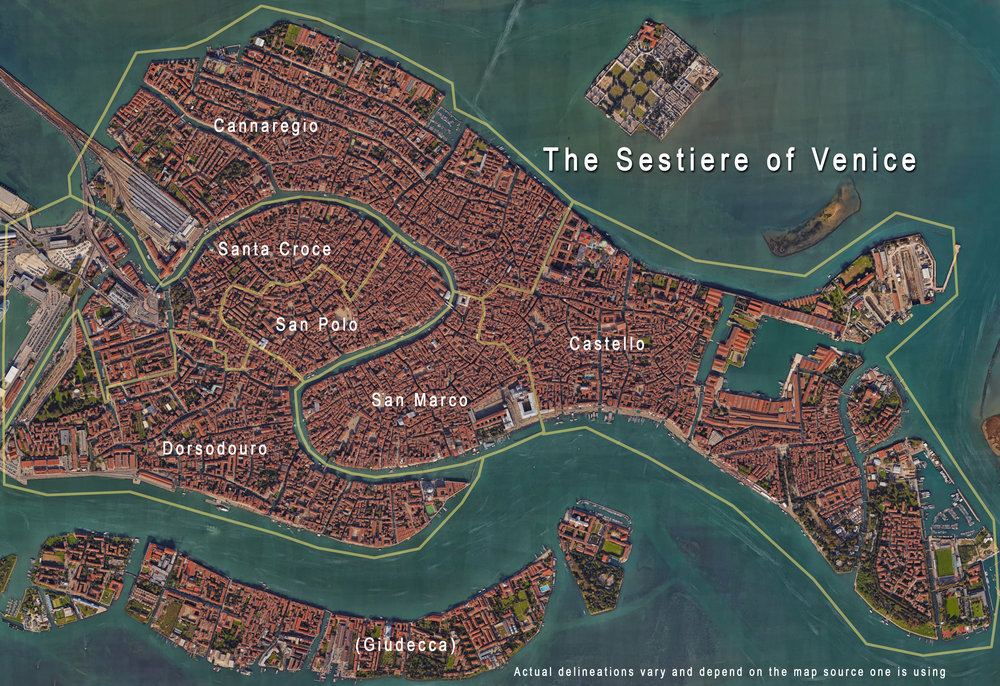

A visit to the Biennale remains, first, a visit to Venice. The city always steals the show as the supreme work of art. I think it is due to its long past as an independent, self-governing city. From 1268 to 1797 (until Napoleon imposed the modern state) its ruler – the Doge – was selected by ‘la Ballotta’, an ingenious system of election and sortition among the thousand or so most prominent families of the city. David van Reybrouck explains how it worked in his book ‘Against Elections’. Venice’s urban plan is barely influenced by hierarchy but seems to have grown organically, as communities responded to the need to combine waterways and streets. Maps don’t work here, even google maps is often off target. I have explored other old European cities that self-governed during the Middle Ages. Each has this kind of organically produced layout, resisting the hierarchies imposed by state planning (the perfect example of the latter being Haussman’s boulevards in Paris). Interestingly, many of these cities have maintained their urban layout, with some modifications, since those Middle Ages, as a reminder that urban societies used to be organized differently.

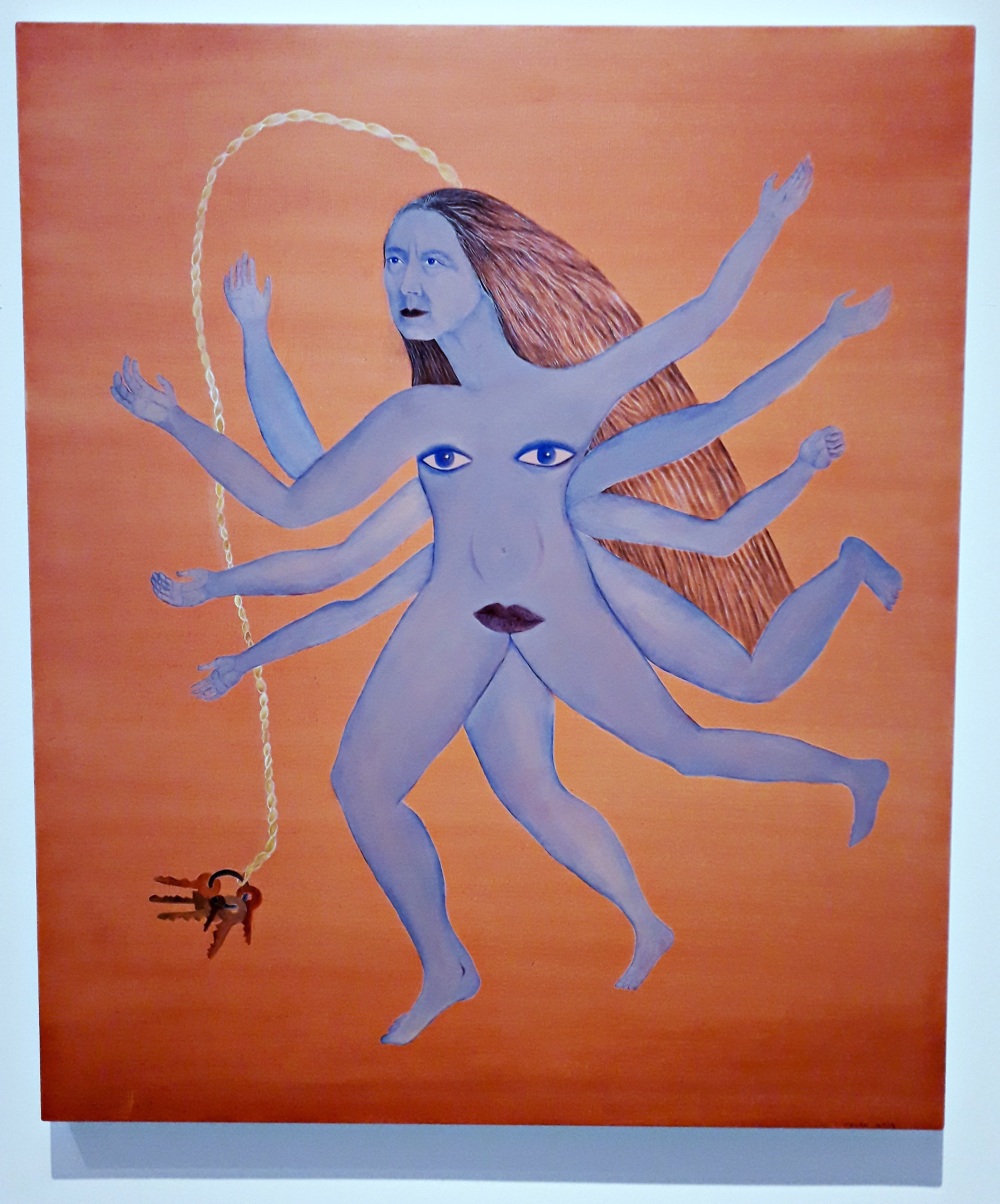

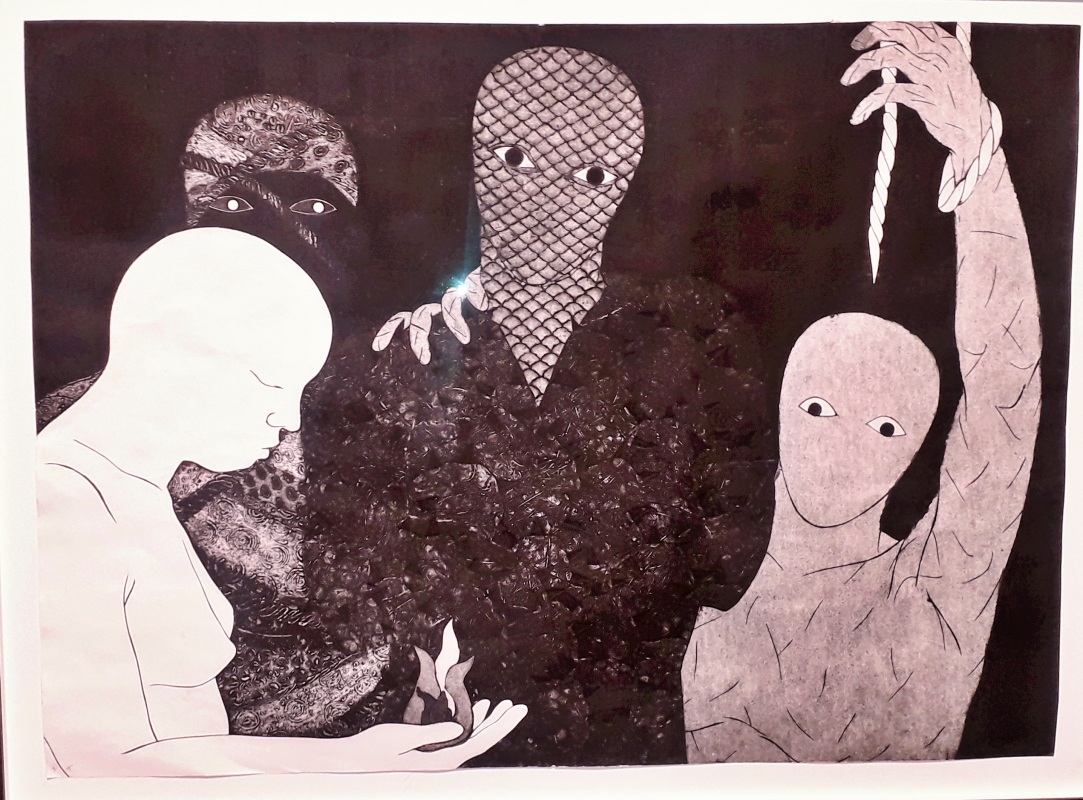

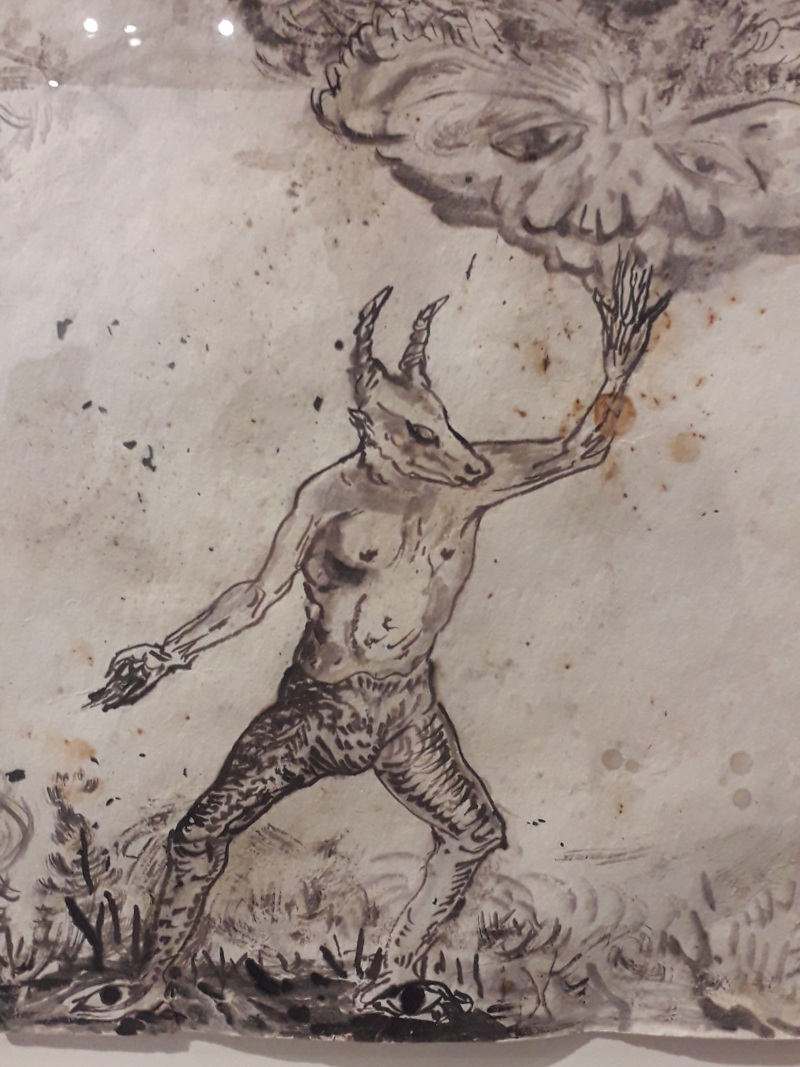

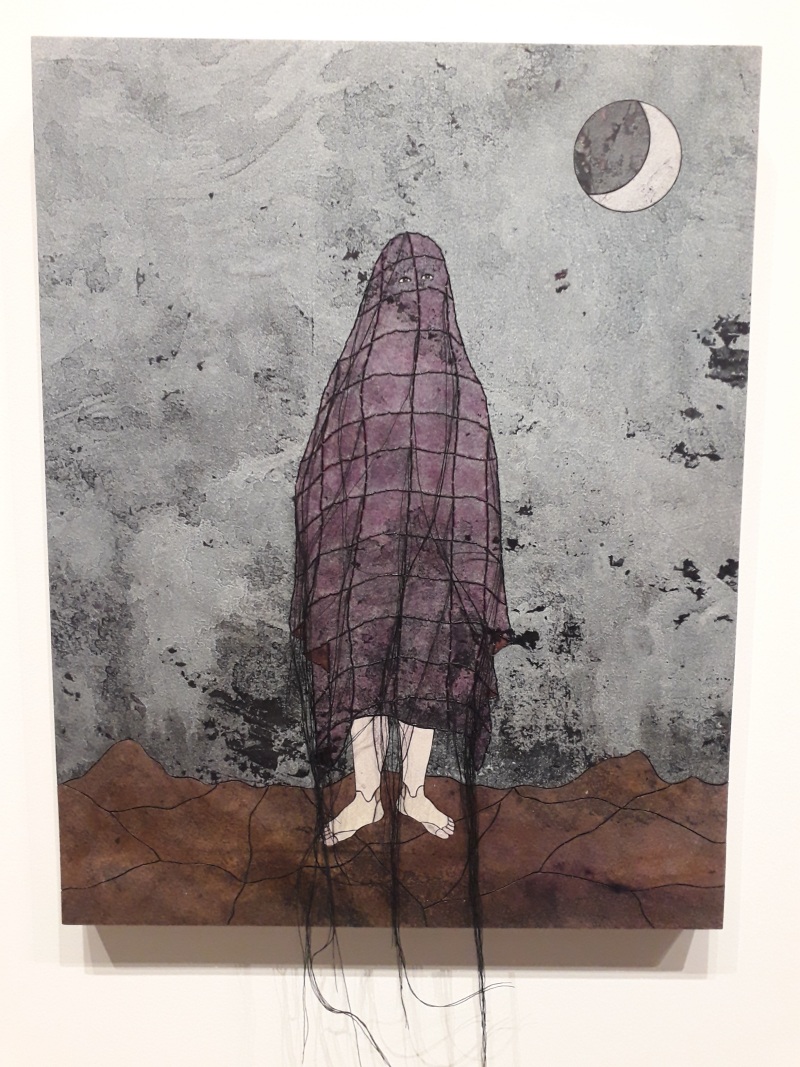

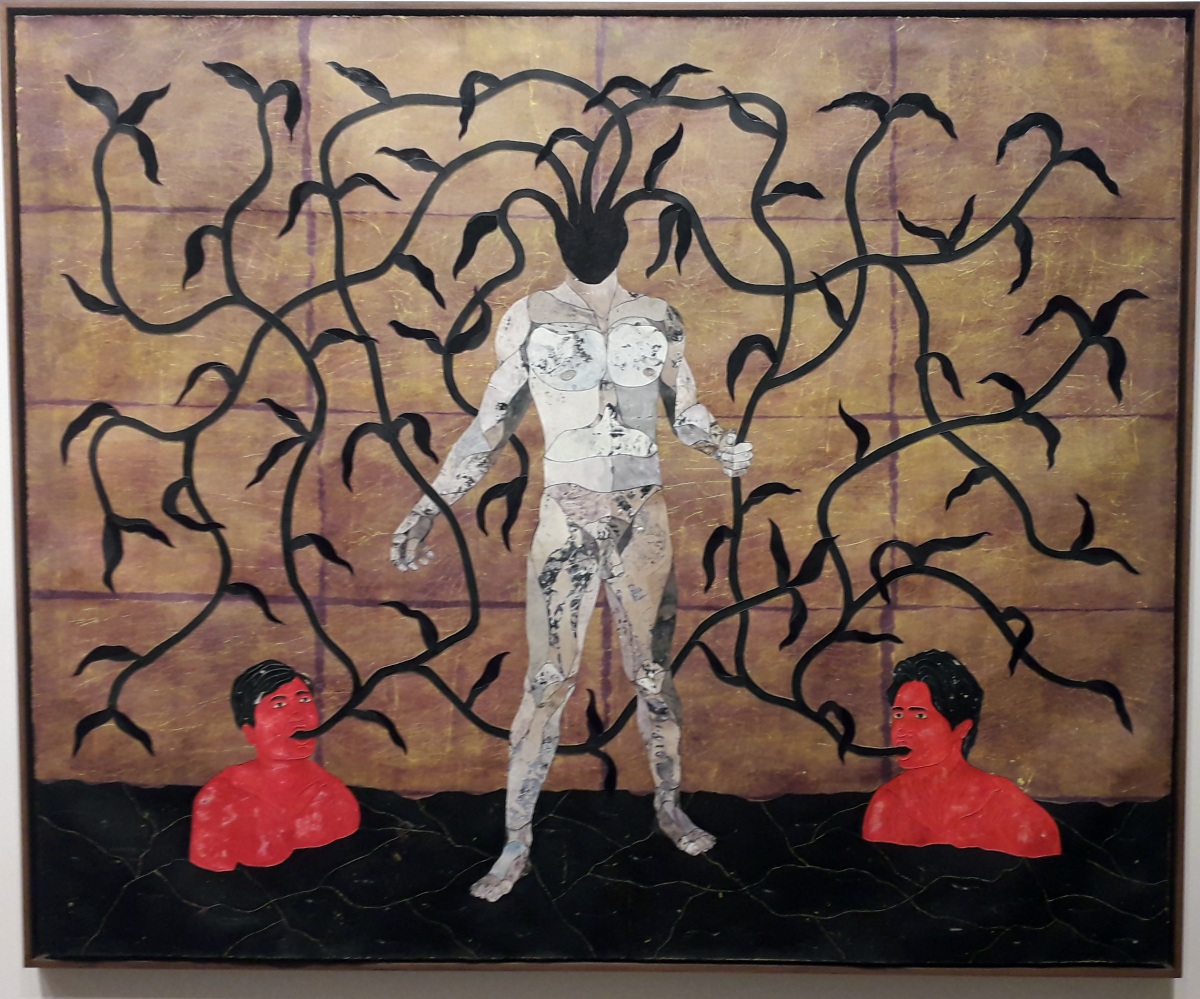

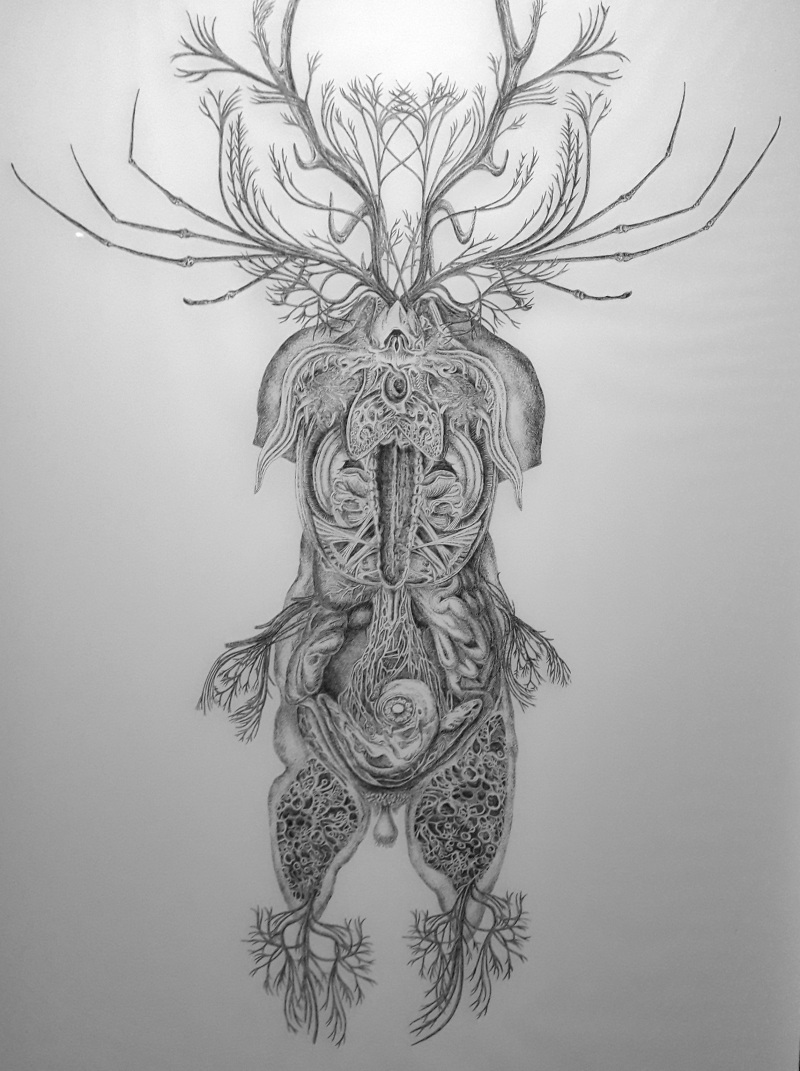

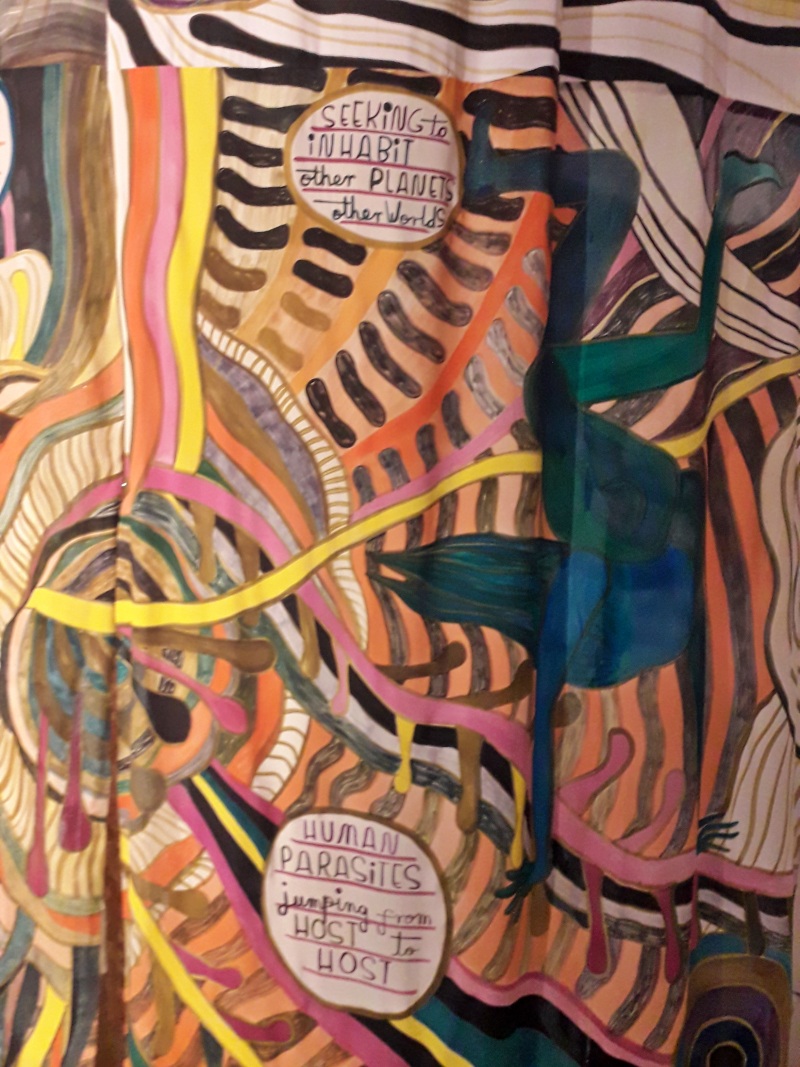

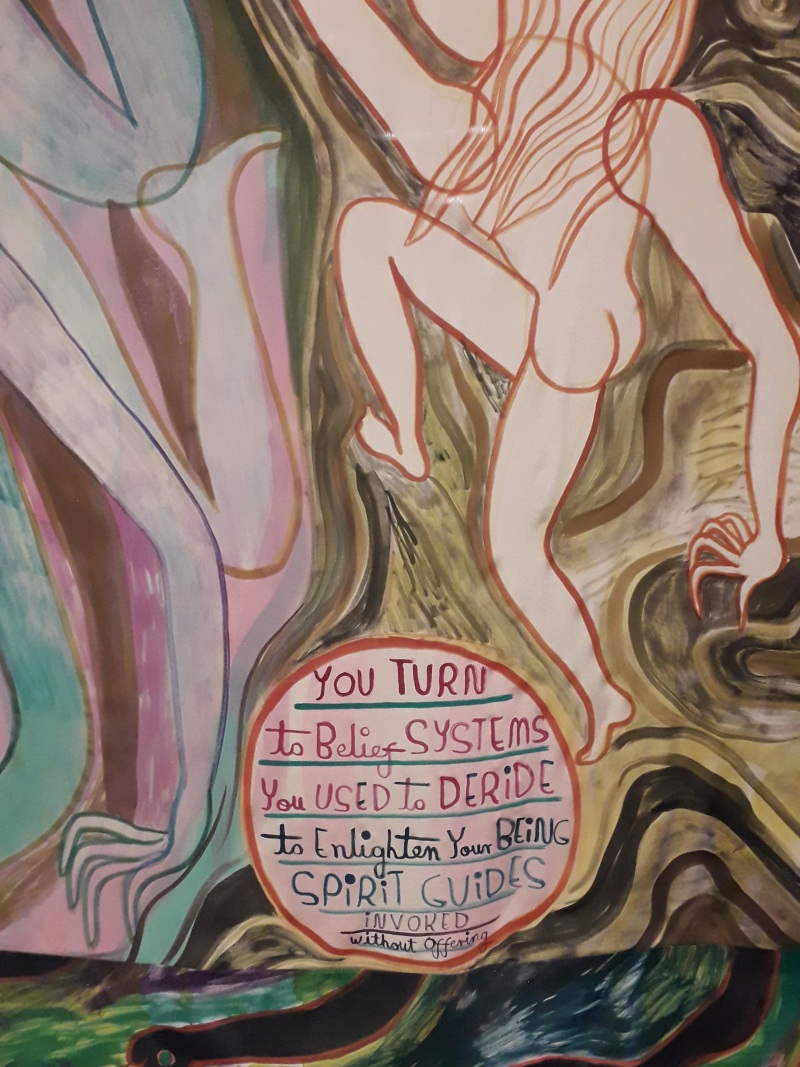

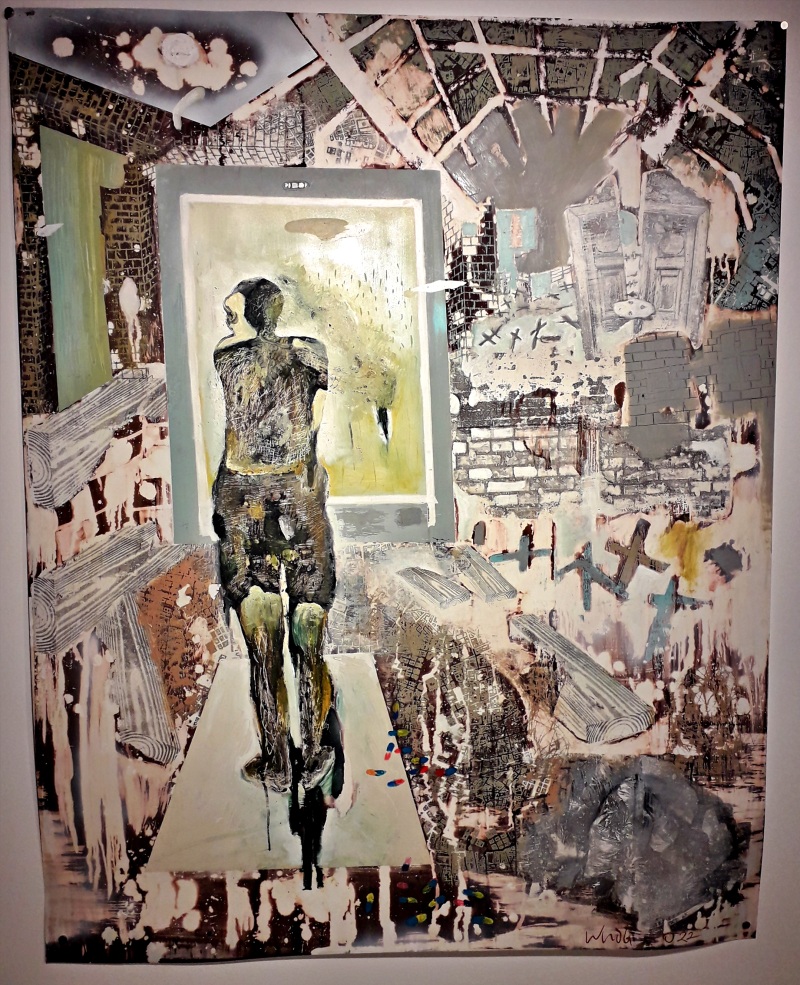

In terms of organizational model, one could say Venice’s urban planning is based on the rhizome instead of the tree. In that sense, this Biennale closely matches the city. It seems much of its art is linked through invisible fungal threads that spread both putrefaction and unexpected new life. Instead of the bright smell of plastic paints that pervades many art galleries and museums, this Biennale smells of mould and decomposition, exactly like the city’s canals. The art is all about the female body, plants, and the voices of distant spirits, relayed by witches, lunatics, ex-slaves and shamen. Technology is also approached from an organic point of view, with robotics and artificial intelligence appearing as an extension of the female body and intuition rather than as a product of the enlightened male mind. Opinions on whether this transformation of the human into the cyborg is successful or even desirable are divided. These themes are reflected not only in the main exhibition, but in many pavilions and side exhibitions too.

The public is something else. Looking at the groups of European pensionados and Italian schoolchildren milling around in great numbers – I had hoped to be nearly alone on this rainy Tuesday and Wednesday in the middle of November – is depressing. There is no human contact, neither among visitors or with the staff. The visitors are dressed badly, make no eye-contact and do not react visibly to the works of art. I found this third level of the Biennale experience – the city, the art, the audience – most puzzling. Artists seem to be desperately seeking ways to save humanity, but that humanity remains obtusely unaware of their efforts.

The art

Where to start? Let’s begin with Simone Leigh, whose giant statue of a black woman greets visitors at the Arsenale. She has also been selected by the USA for their pavilion, with a beautiful show called ‘Sovereignty’. Here’s what the curator’s says about the exhibition’s subject, very close to how I define the term in the PhD thesis I recently submitted. “The works in Sovereignty collectively extend the artist’s ongoing inquiry into the theme of self-determination. The exhibition’s title speaks to notions of self-governance and independence, for both the individual and the collective. To be sovereign is to not be subject to another’s authority, another’s desires, or another’s gaze, but rather to be the author of one’s own history. Many of the featured sculptures interrogate the extraction of images and objects from across the African diaspora and their circulation as souvenirs in service of colonial narratives. Though Leigh’s figural works present their subjects as autonomous and self-sufficient, they do not simply celebrate the capacity of Black women to overcome oppressive circumstances, but rather indict the conditions that so often require them to affirm their own humanity”.

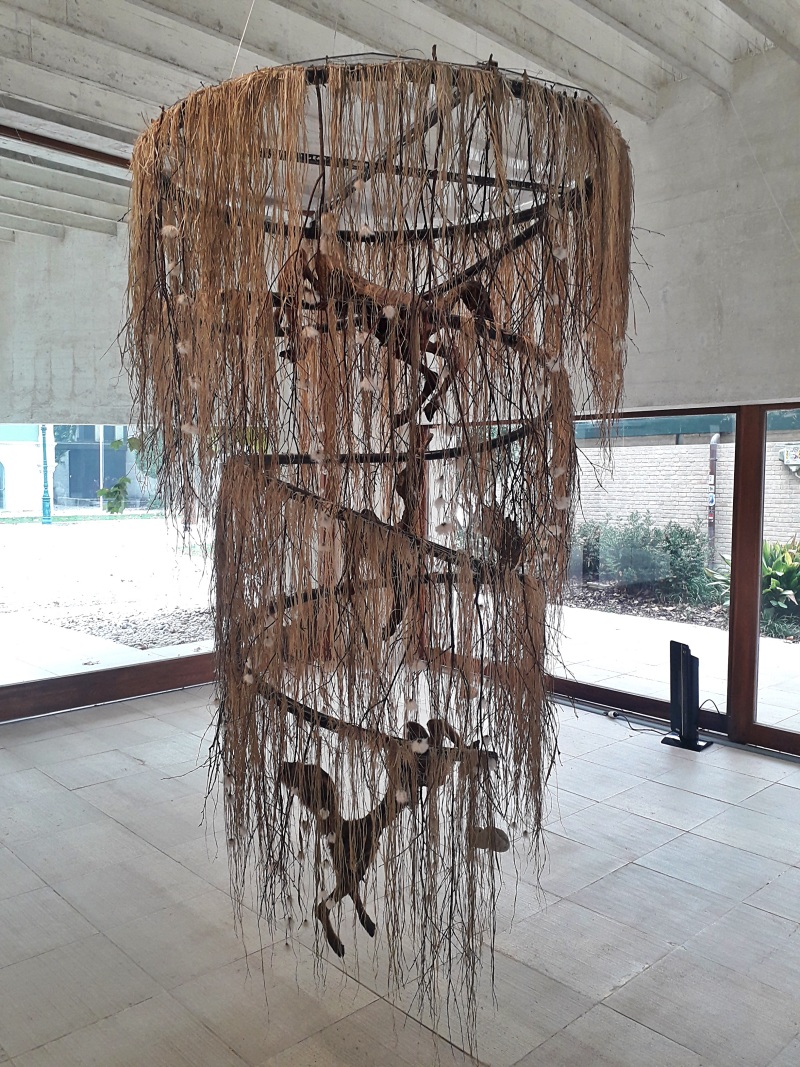

The theme of self-sovereignty returns in other parts of the Biennale, notably in the adjacent Sami pavilion hosted by the Nordic countries. An old lady speaks about the spirits of the rivers and lakes and how they used to interact with the Sami families that live from them. Stuffed animals hang in a coccoon-like net close to the trees that still grow through the Nordic pavilion. Opposite it a very big wooden wall depicts the progressive colonization of the Sami people and their territory by the States of Sweden, Finland and Norway. The panels of mural-like paintings are framed by books, supposedly containing the laws and the documentation of how they were applied to rule the Sami people. The last panel is burnt, only a heap of burnt wood and ashes remaining, in a symbolic effort by the Sami artists to reclaim their history.

Opposite this, in the pavilion of Denmark, life-like dead centaurs can be found: one has hung himself from the ceiling, while another lies motionless in what seems to be a stable. “We Walked the Earth” is the title of the Danish show.

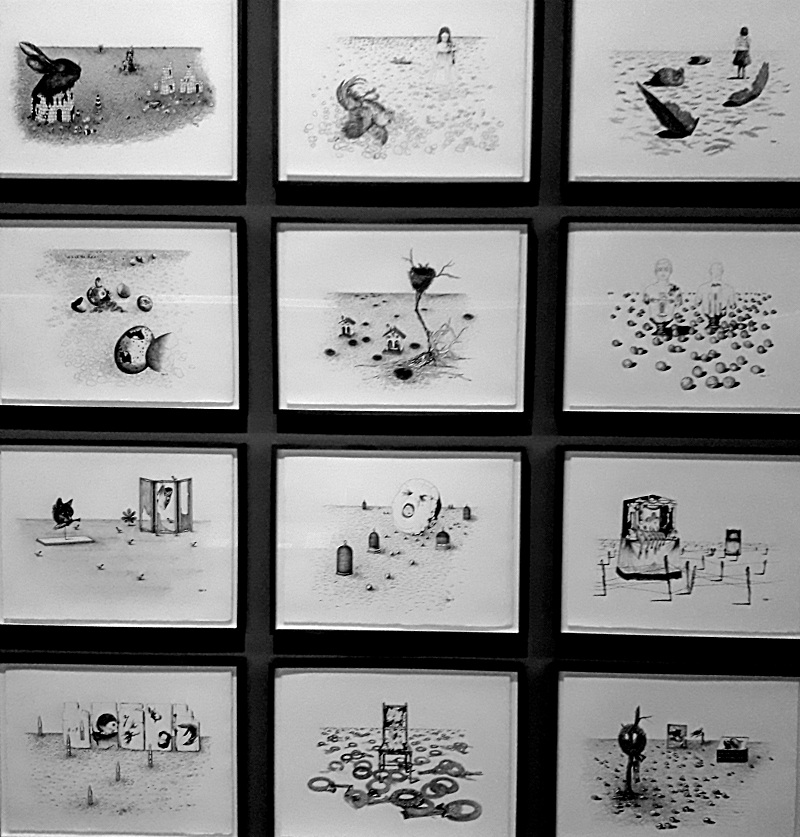

It is maybe a bit too literal. A much more subtle approach, echoing the Sami shaman’s words, is that of Dai Wenhua, an off-side event in Cannaregio. Two giant ink-scroll paintings express an “Ode to the Nymph of the River Luo”, in an intriguing exhibition combining urban-rural development plans, a dreamy abstract video and small installations.

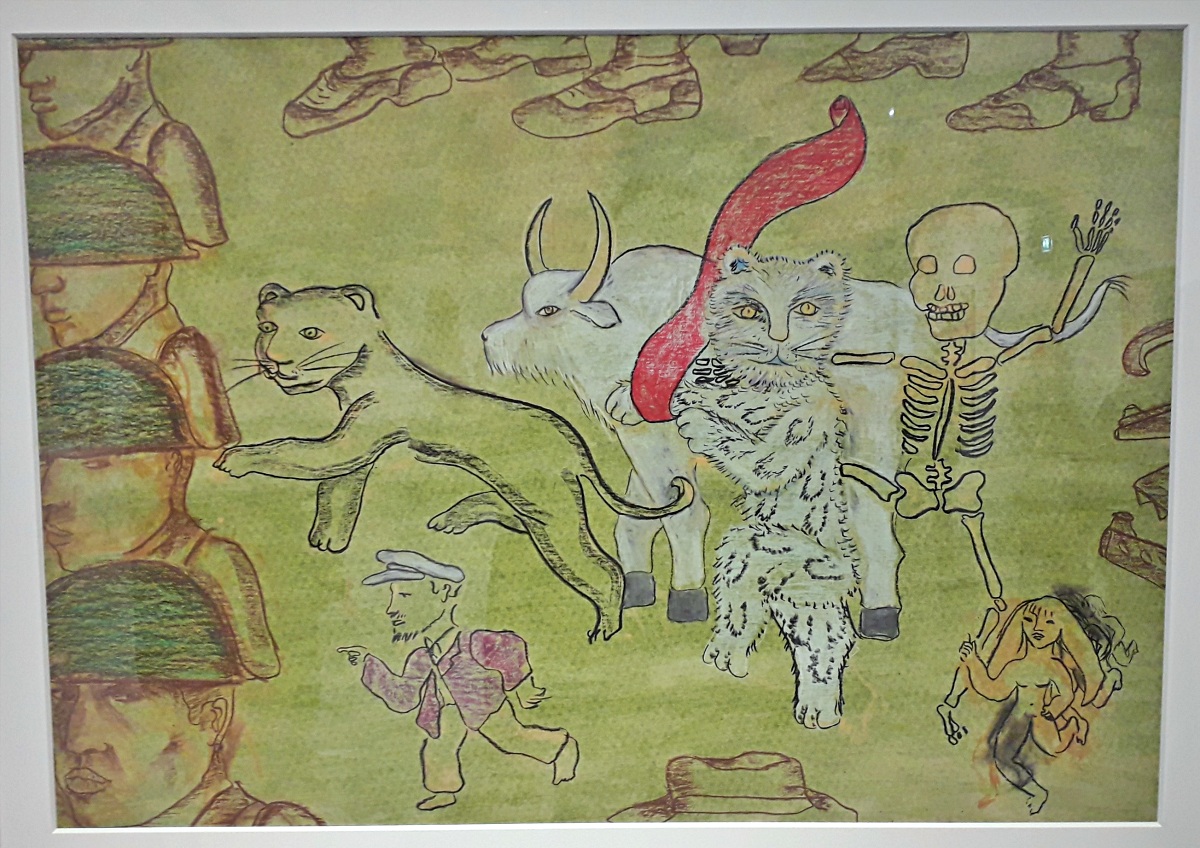

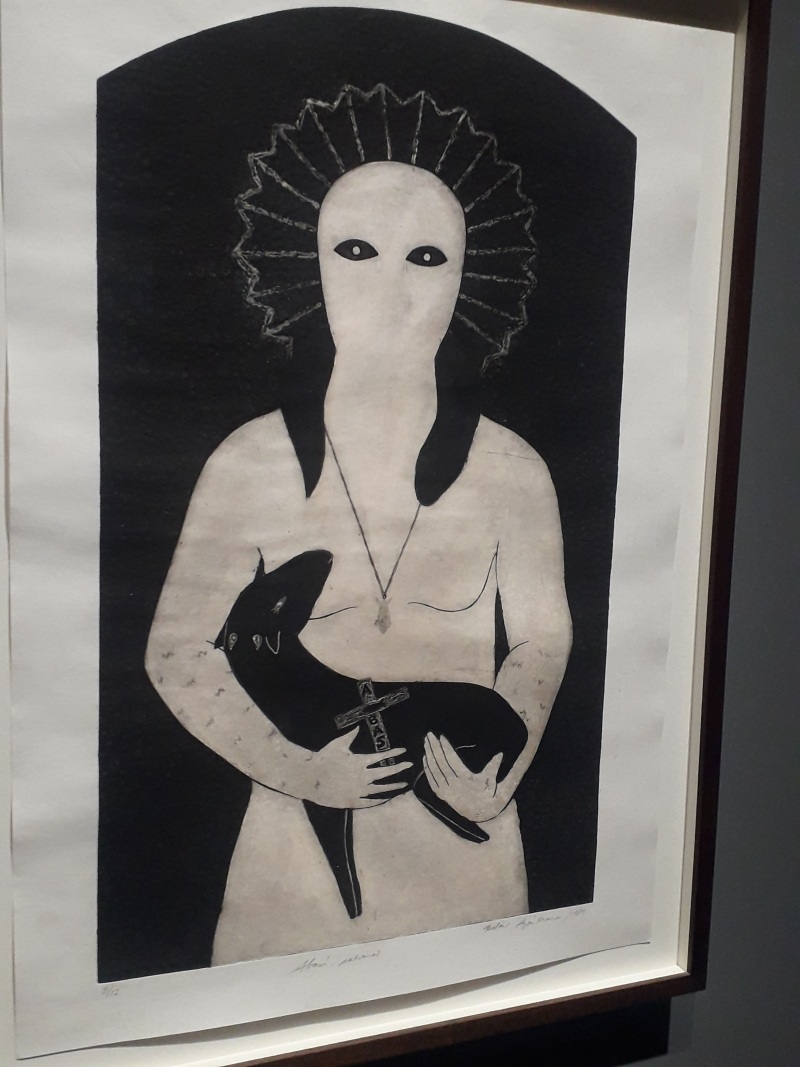

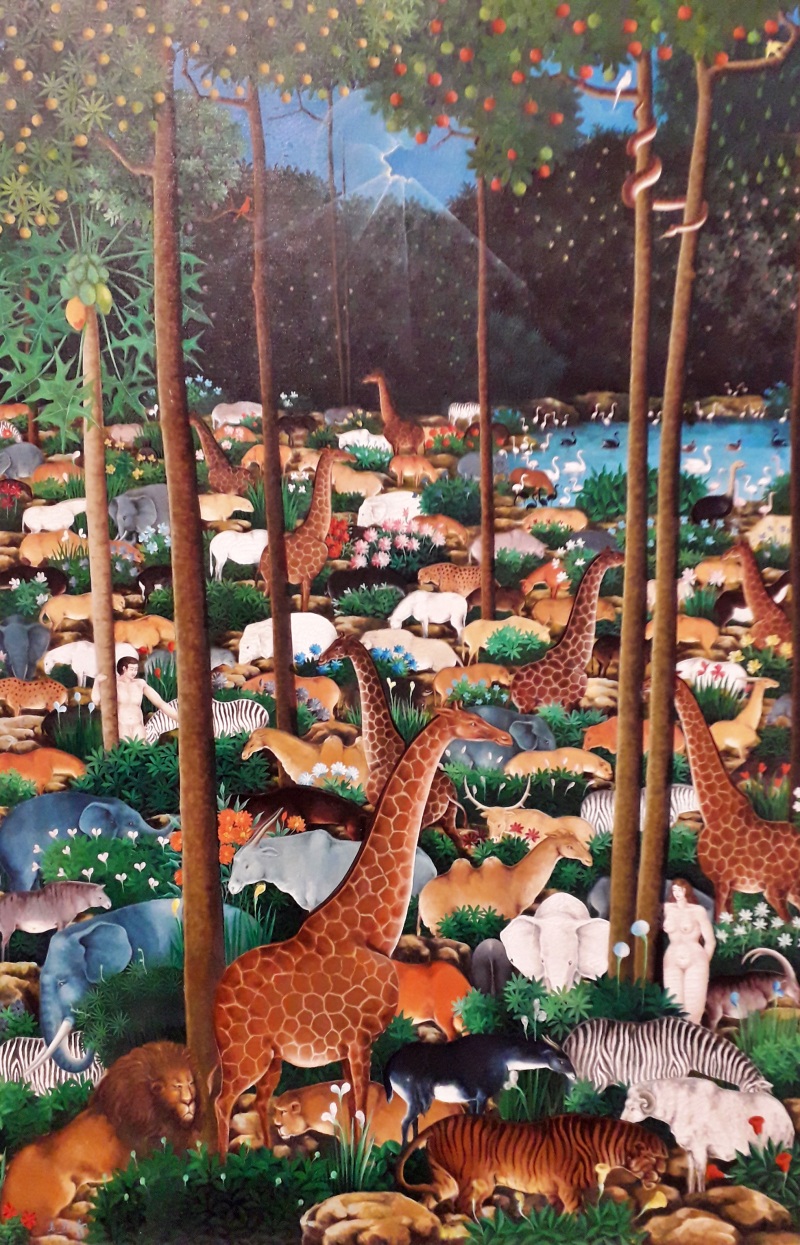

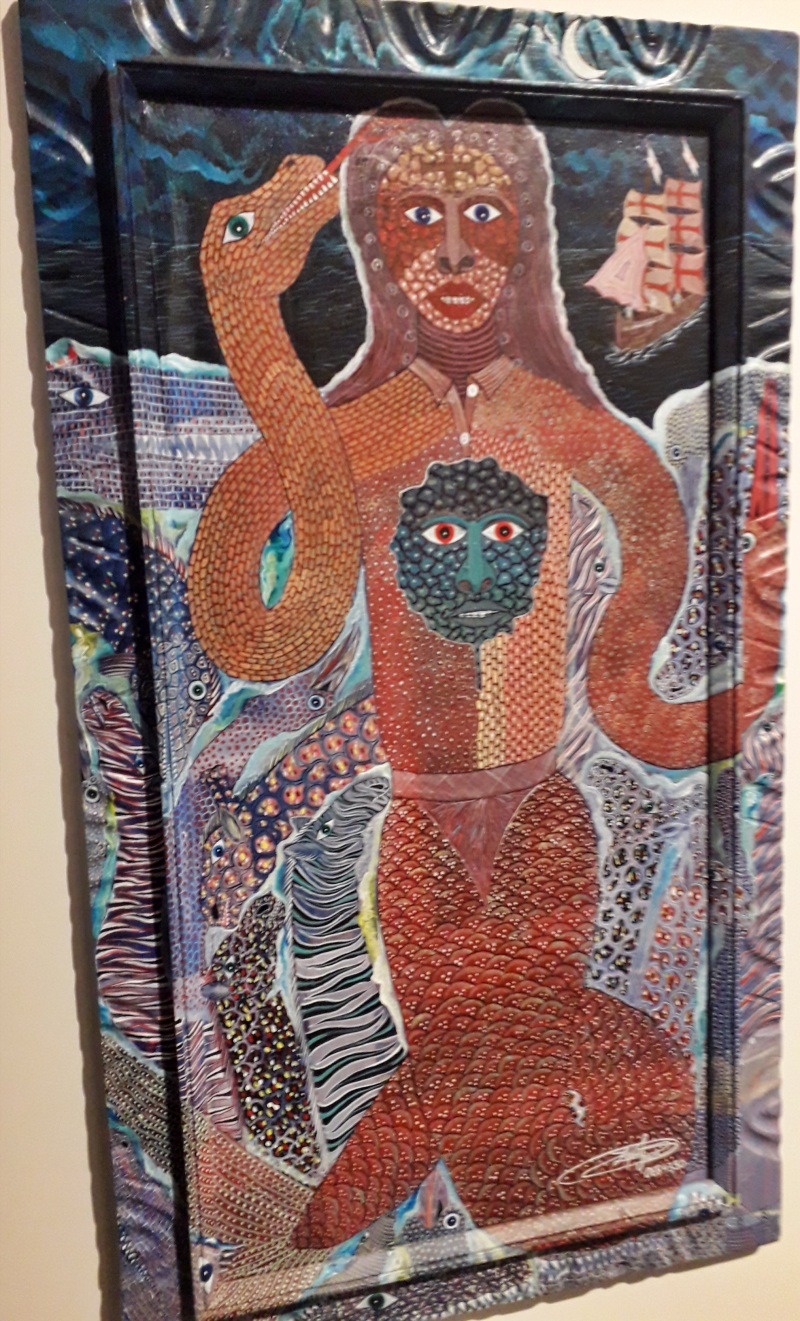

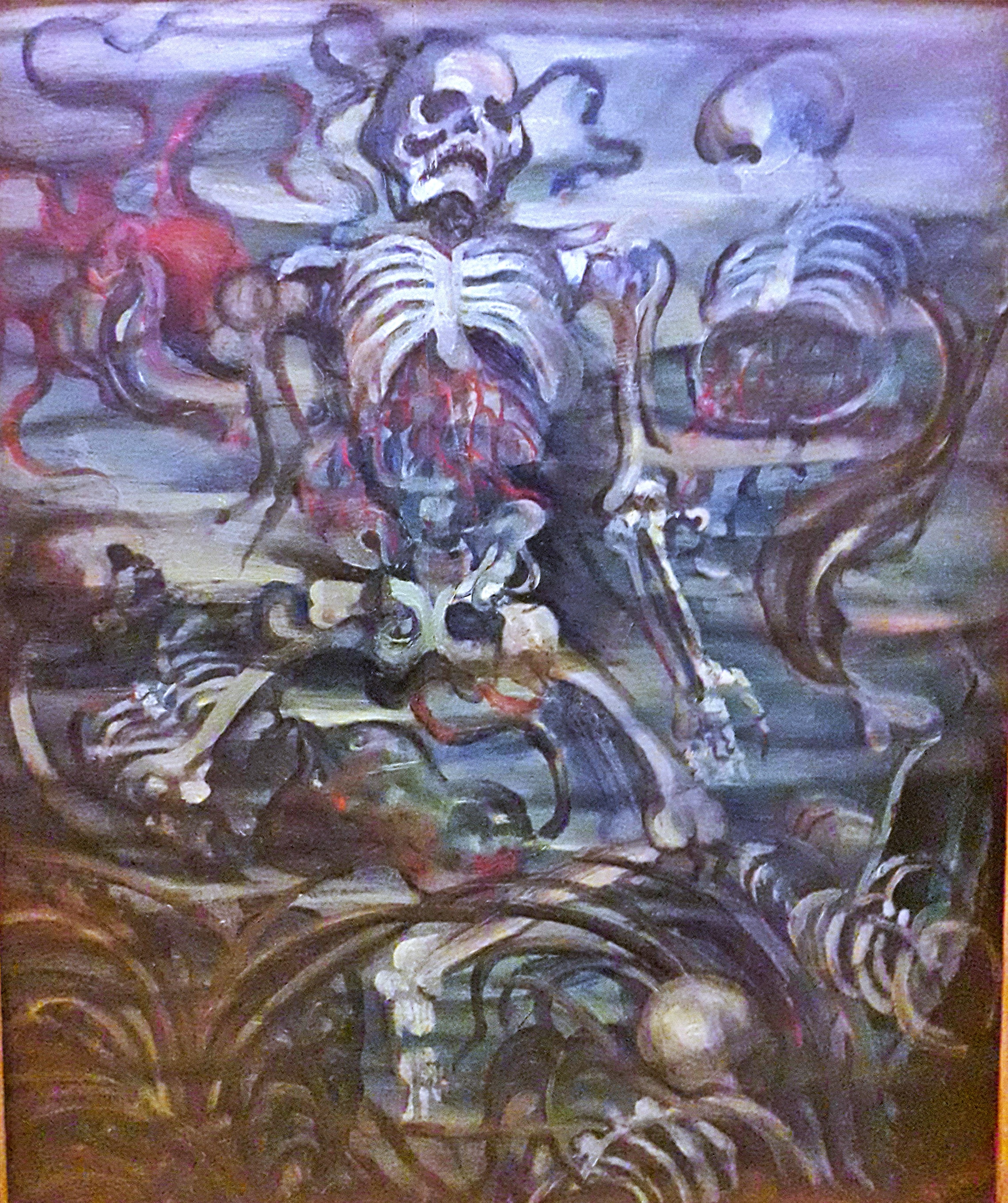

Spirits, especially the chtonic and sometimes violent emanations of Mother Earth, are very present in this Biennial. They perfuse the paintings of Cecilia Vicuña, of Belkis Ayön, of the three Haitian artists in the Arsenale – Frantz Zéphirin, Célestin Faustin, Myrlande Constant – and the giant installation of earth and invasive creeper plants and the unfinished golem-like shapes arising from it by Okoyomon, which provides a grand finale to the ‘Milk of Dreams’ exhibition in the Arsenale.

Leaving the exhibition I was frankly stunned. The video by Diego Marcón showing a family of dolls describing how they were all murdered by the father, that is shown near the end, did me in. But after a quick smoke I stumbled into more vengeful spirits in the Mexican contribution to the Biennale, ‘Hasta que los Cantos Broten’ (Until the Songs Surge Up). A crazy but gripping video by Santiago Borja shows Mexican actors dressed up as the vengeful indigenous spirits of nature emerging from polluted ponds and derelict urban settings to punish humans for their transgressions. Meanwhile, the main piece of this exhibition is an enormous installation of rag dolls dropping from the ceiling in a mechanical dance.

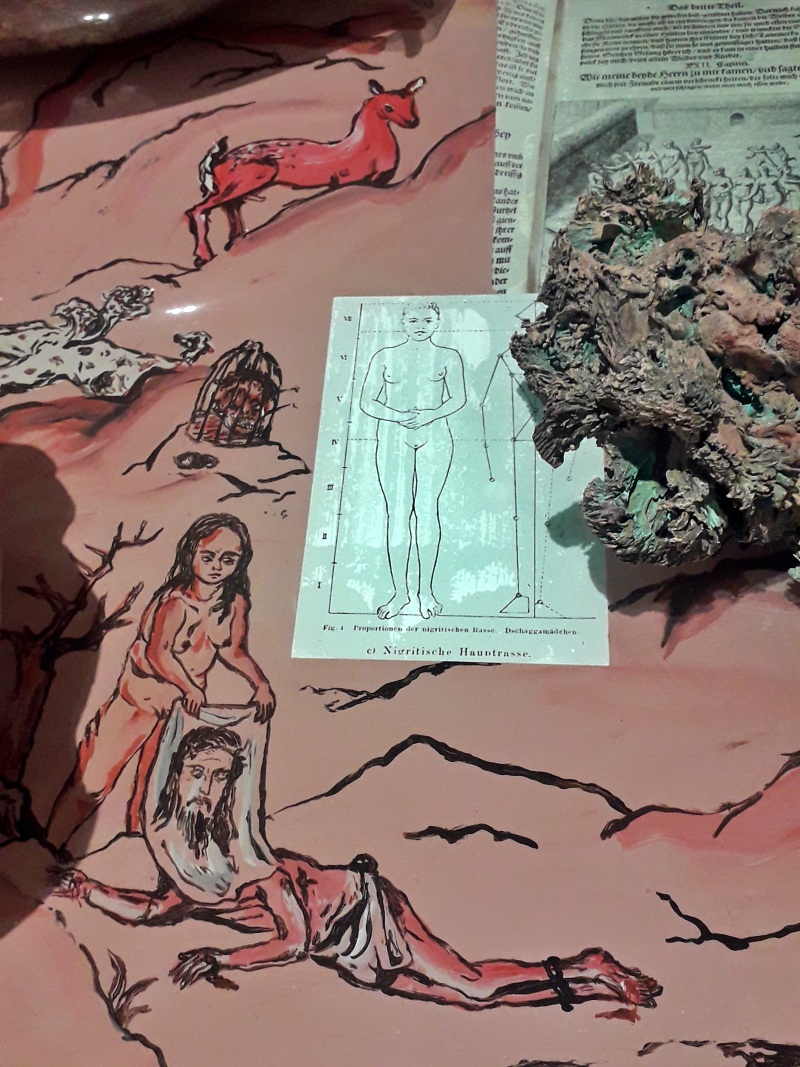

Alchemy is a theme here related to the effort to reclaim the repressed female (and often black or indigenous) body. Candice Lin’s installation Xternesta was probably my favourite in the entire Biennale. She transforms clay from hallowed places into cabinet-like sculptures, and four big tables intricately illustrated and littered with documents, objects and alchemical equipment (such as the alambic) represent efforts in progress to resurrect and unleash the repressed magic.

This same theme, of the alchemy of primal female energy, often leading to rebellion or even madness, is captured beautifully by the curator in The Witches’ Cradle. It is one of five capsules the curator has inserted in her exhibition to provide historic depth to her themes. This is a brilliant curatorial device. The Witches’ Cradle traces the history of female artists around surrealism and its precursors; they were often spurned by the macho surrealists, and many of them went their own way.

The theme of madness comes back strongly in the work by Ovartaci, a Danish artist who spent most of her life in a mental asylum. But the witches’ power is evident in many other works; Paula Rego’s paintings and installations are eery, as is Aneta Grzeszykowska’s serie ‘Mama’, where she photographs her daughter playing with a lifelike latex cast of her (the mother’s) upper body.

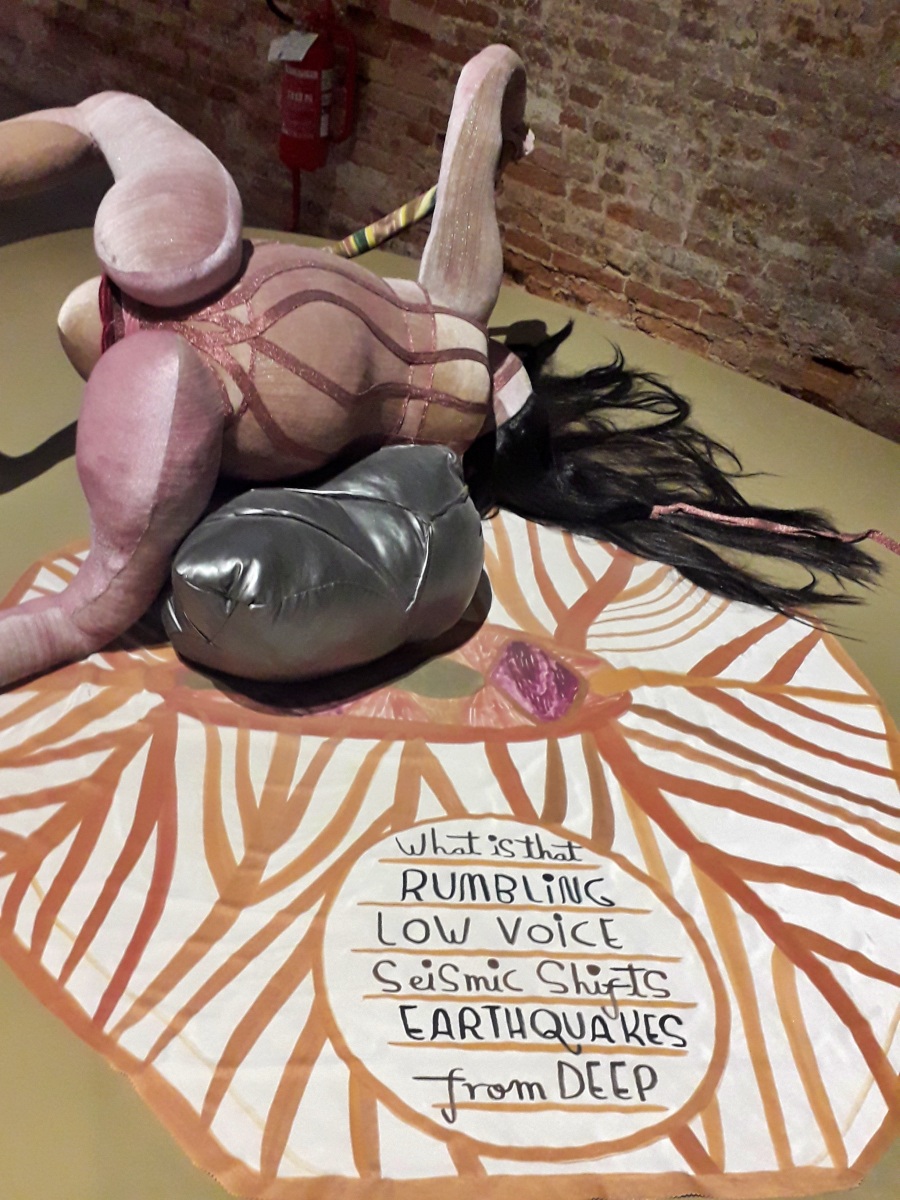

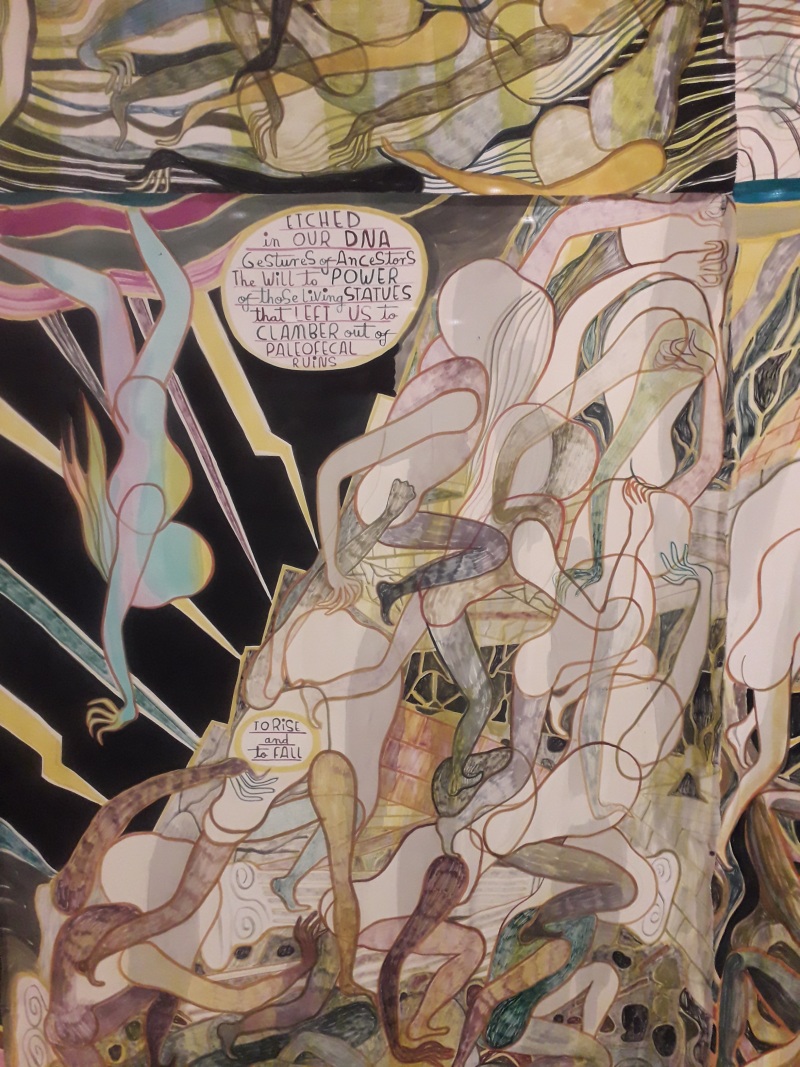

Dolls are a constant theme of Alemani’s exhibition, and much of the sculpture also tended towards the doll-like, such as Ali Cherri’s ‘Titans’. Emma Talbot’s installations, and those exhibited in the Mongolian pavilion, all seem to writhe in pain, as if they are about to give birth to deep and dark forces.

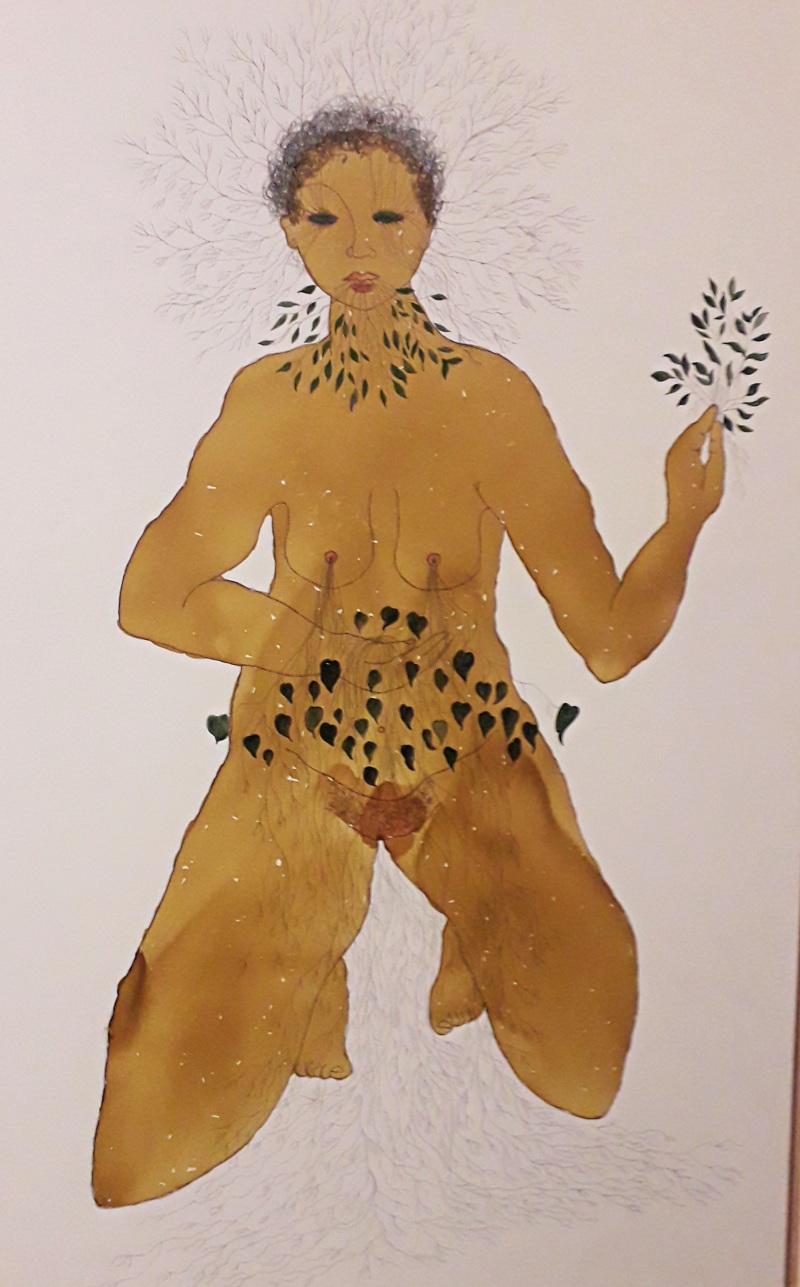

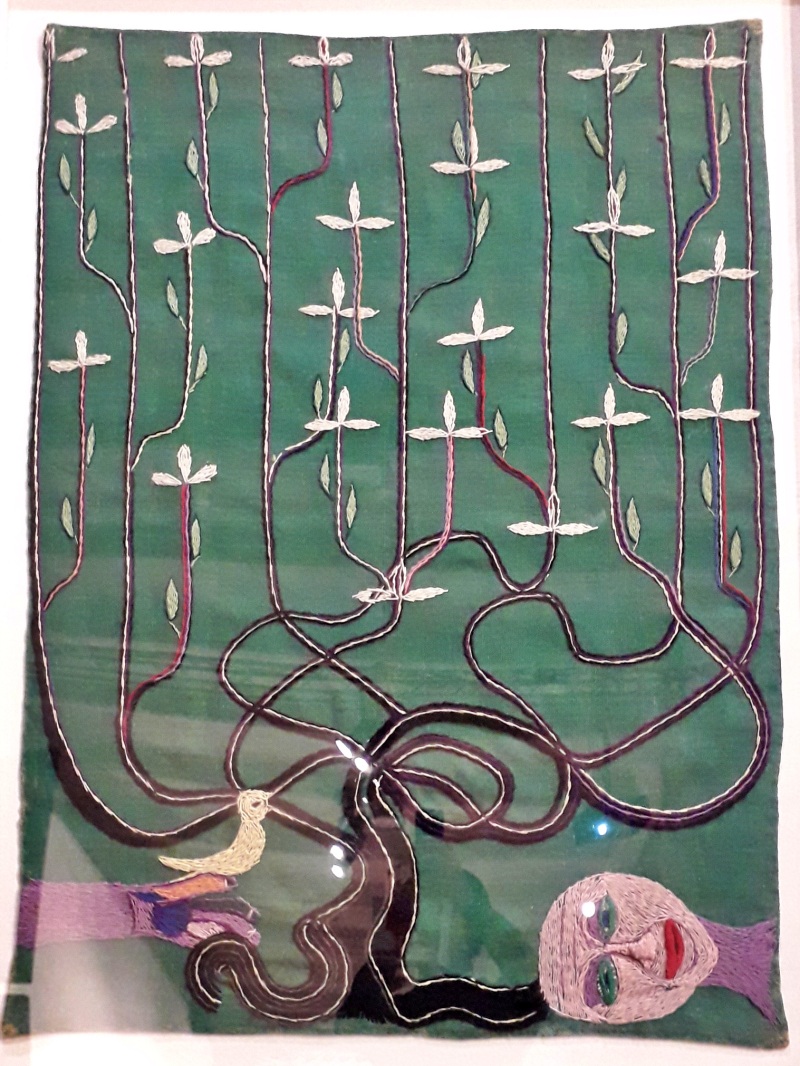

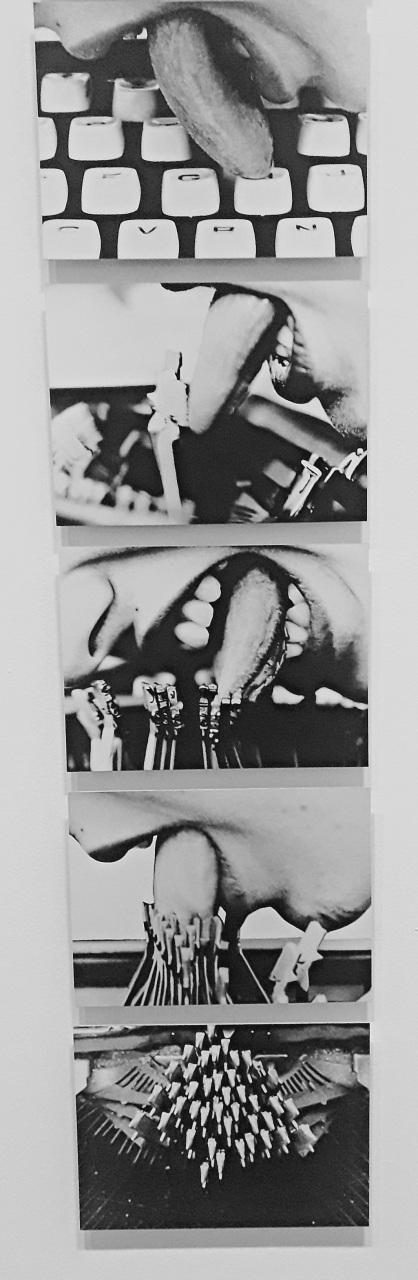

Another theme is the continuity between the female body and plant life, as in the work of Rosana Paulino, an embroidery by the Chilean singer Violeta Parra, and a painful exhibition in three subsequent spaces of the Venice Pavilion (in the Giardini) occupied by an installation by Paolo Fantin and Ofsina called Lympha. The corner of a bed that a grieving woman sits on is transformed into ashes and then covered by a plant. Angela Su in the amazing side show ‘Arise, Hong Kong in Venice’ was one other artist exploring how body, plant and machine come together. In Felipe Baeza’s work a very aesthetic version of this same theme could be found. In a way even Zheng Bo’s video ‘Le Sacre du Printemps’ where men are seen imitating sexual acts with trees in a boreal forest, responds to this theme of human-plant fusion.

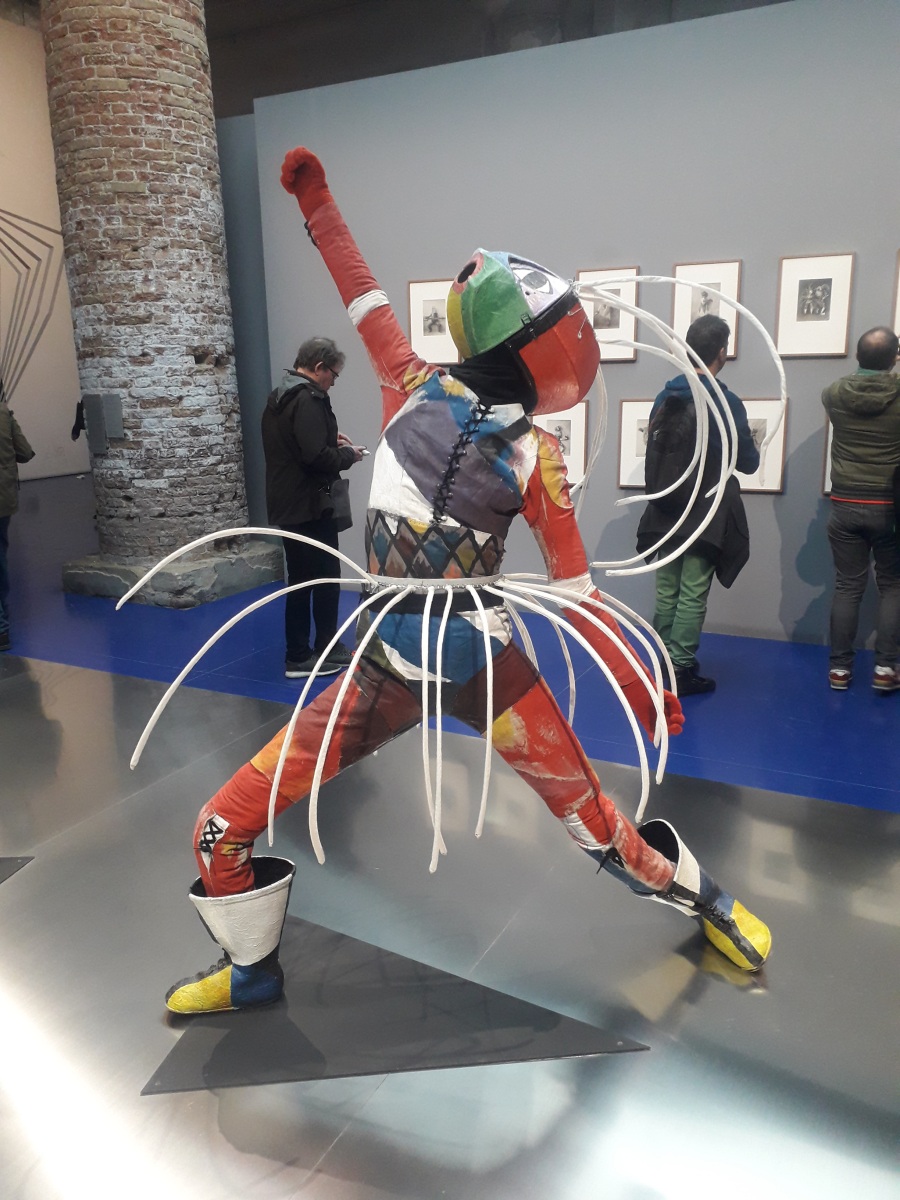

Dolls, masks and primitive unfinished sculpture kept returning in this Biennale. Sometimes very directly, as in Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s video ‘Maintenancer’ about a German sex-doll brothel, where bored German employees talk about their work maintaining the dolls for the maximum satisfaction of their male customers. A series of astounding Bauhaus-style costumes were displayed in a curator’s capsule dedicated to the cyborg, the mix between human and machine. This capsule, which featured many photographs of early feminist cyborg fashion, and excerpts of the Soviet science fiction movie of 1924 ‘Aelita, Queen of Mars’, was a beautiful introduction to the last part of the Milk of Dreams exhibition, honing in on how tech is transforming our bodily experiences.

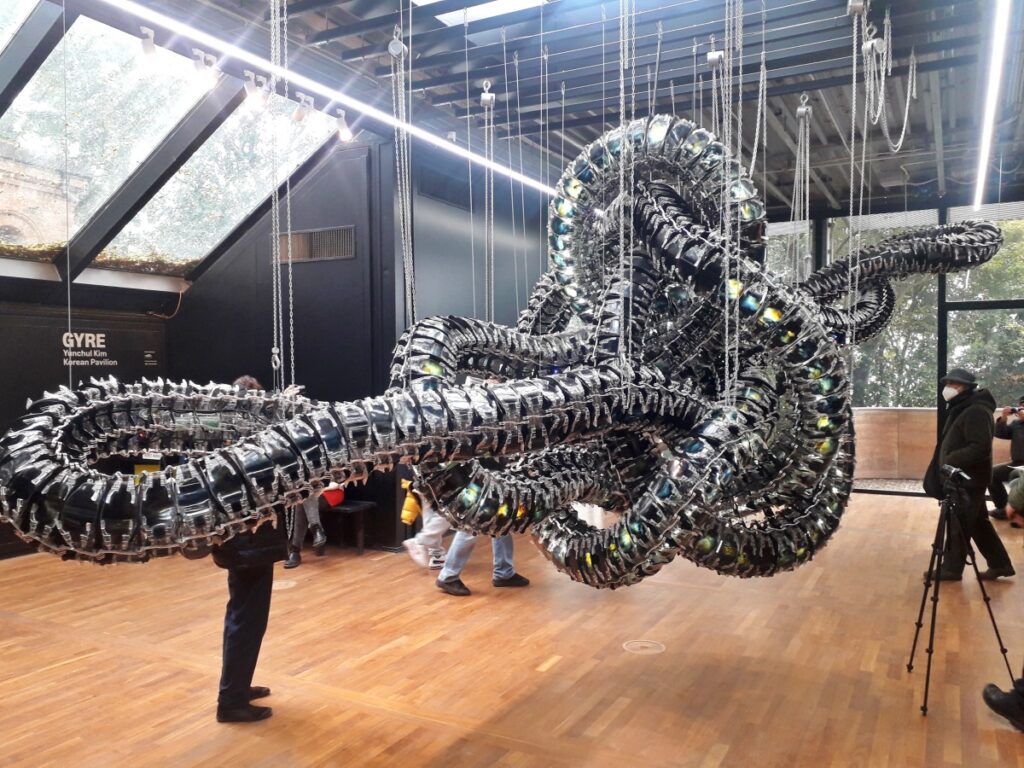

What made this art really intriguing is that the extension of the human body by machines is usually seen in a very male, Apollonian way: as the path to a fantastic future in which man perfects his domination over matter by multiplying his capacity through the machine. But in this exhibition technology was more often seen as an organic extension of the primitive body, either to express or replace (rather than truly overcome) its deficiencies. Technology here is inform, instinctive, often purposeless, inhabited by random impulses; but it still transforms the human body. Maybe the most stunning example of this was the giant sculpture ‘Gyre’ by Yunchul Kim in the Korean Pavilion; like a giant robotic snake driven by its own impulses, it moved its endless scales, different lightings emerging from within, in a mesmerizing process.

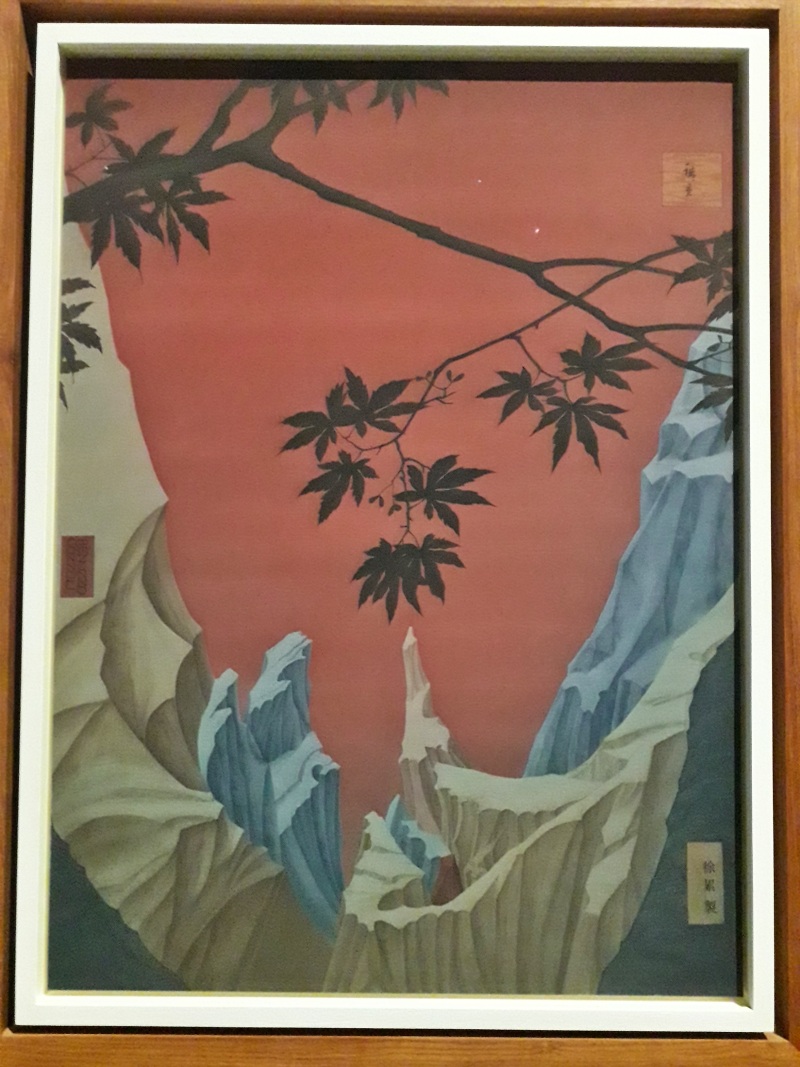

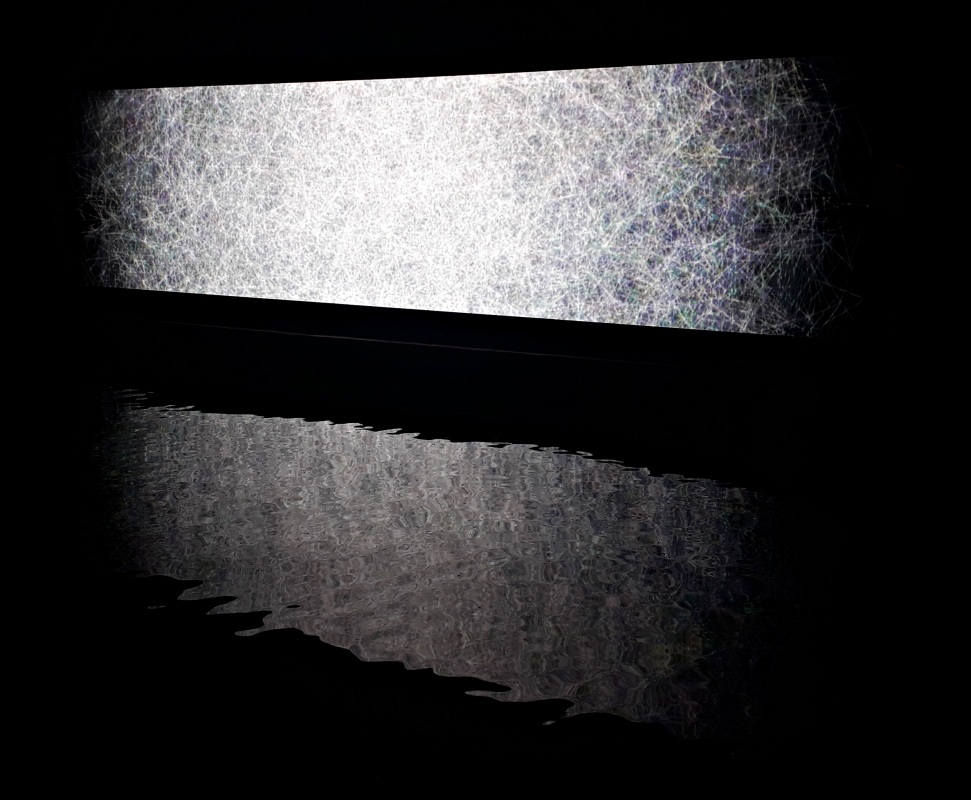

Several Chinese artists developed this theme of the human connected to the machine rather by intuition than by rational purpose. I would have liked to see Wu Tsang’s 6-hour video ‘Of Whale’, that reflected onto the water from a giant screen near the end of the Arsenale terrain, in its entirety. The little fragment I saw seemed to depict a rhizome of acoustic sound waves lighted in the dark waters, warped by the passage of a whale underneath. Alas, I had little time left. In China’s nearby exhibition, a tree had been cut and was suspended from the ceiling in its normal position. After several months of Biennale its leaves had gone dry but were sill attached. A strange, enormous colourful folded metal object seemed to have crashed into it horizontally. A series of prints also showed strangely warped landscapes.

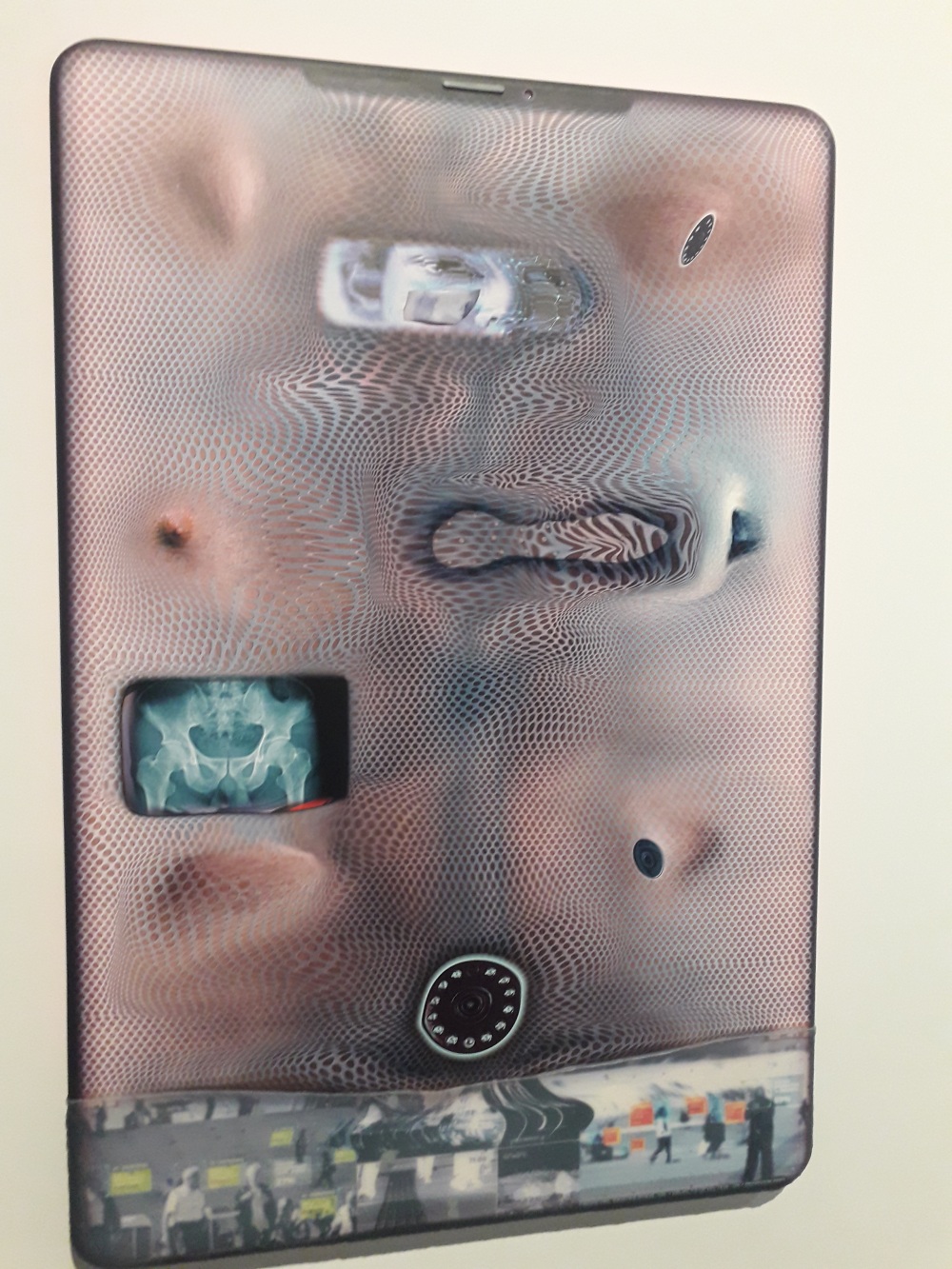

Tishan Hsu exhibited a morbid installation of medical equipment and giant mobile phones in the Arsenale that seemed to be disposing of the last vestiges of human bodies. Nearby, LuYang had a three-screen installation called “Doku – Digital Descending” which takes the viewer through a series of reincarnations of the protagonist through heaven and hell, with a tension between his superpowers and his bodily limitations and fears, this all in an anime game arcade-like frenzy. For a taste of his art (a video and dance performance in the Garage, Moscow) see here. Shuang Li, meanwhile, displayed a film where her body morphs into social-media like app-scapes, suggesting its sensuality has become entirely digital. Another take on this theme was Lynn Hershman Leeson’s wall of AI-generated human faces, of people who look perfectly real.

Then there was a strange streak of Caucasian and Central Asian spirituality, departing from Armenia’s exhibition ‘Gharib’, about the sensation of not-belonging, of being in dissonance, through sonic sculptures installed in a simple, almost nomadic way. I sat down in front of a giant curved brass plate that was resonating with the soundscape, and was immediately plunged into a deep meditative vision. The nearby room, where the music seemed directed at enneagrams drawn onto the wall, was equally rapturing. I asked the exhibition staff how it was to sit there every day, and they told me they hated the soundscapes. That I can also understand.

The Uzbek artist Saodat Ismailove had a three-screen projection about the Chelhona, the little space often adjacent to Central Asian shrines I am familiar with from Afghanistan, where they are often used by chilum-smoking ‘malangs’. A place of spiritual withdrawal and meditation. The Uzbek pavilion ‘Digital Garden’ pandered to the same theme of meditative spirituality but it was too slick to my liking. What did really do justice to the theme of a place to practice and develop one’s inner being was the Kirghiz Pavillion, far way on Giudecca. It took me nearly 45 minutes to find it, but Janet Rady’s exhibition of Firoz Farmanfarmaian was absolutely worth it. Behind a series of colourful felt tapestries he had designed was a little space in the dark where I felt tempted to sit and meditate, looking at a strongly slanted projection of the shores of what is probably lake Issyk Kul in Kirghizstan.

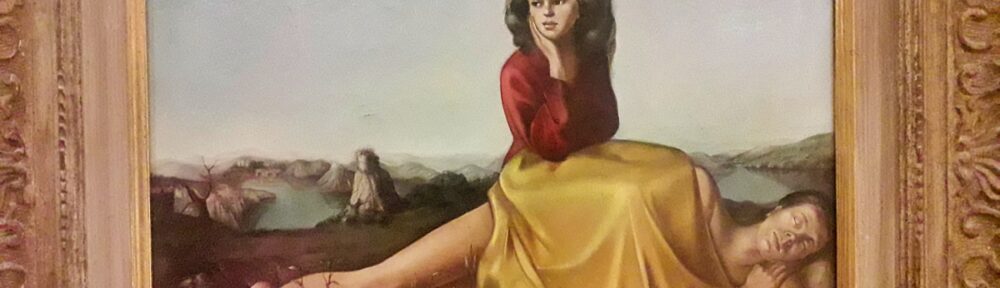

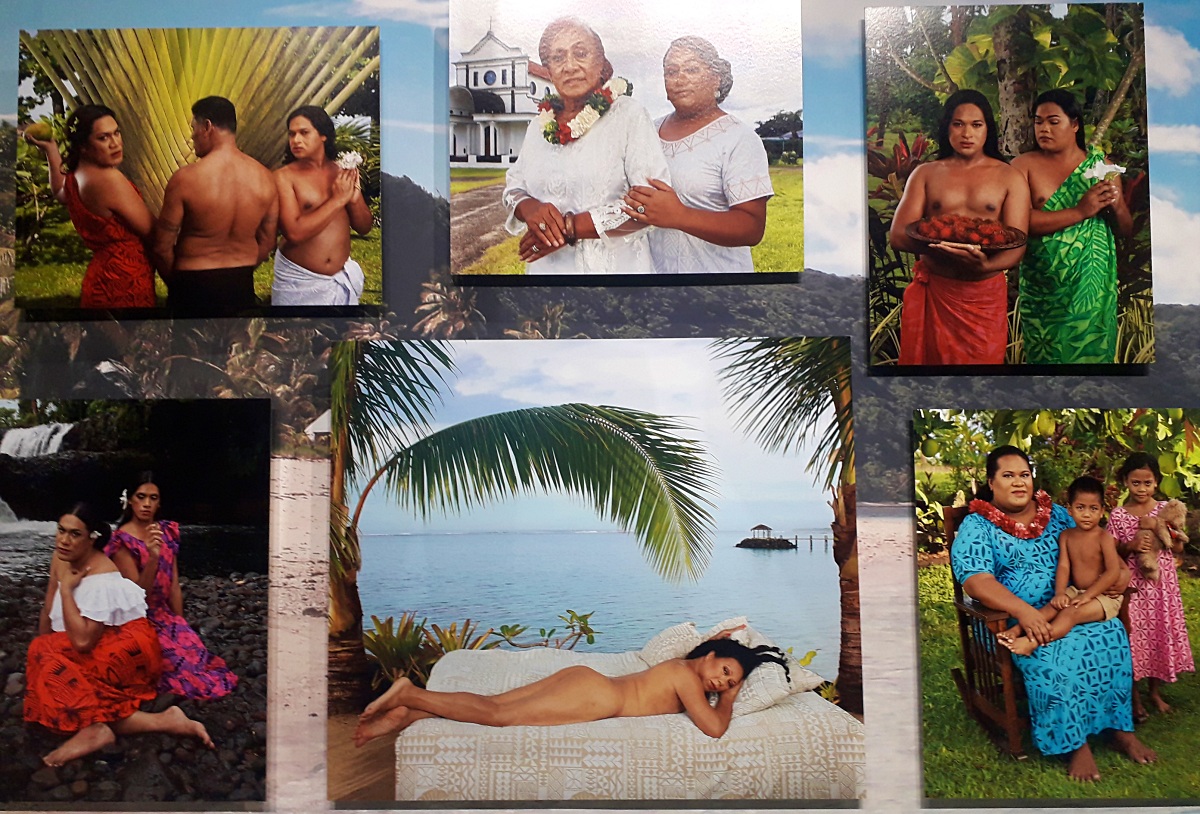

Altogether this is really a shaman’s biennale, in which the Pandora’s box of repressed spirits of mostly female energy has been opened wide. Like in the text about ‘Sovereignty’ above, there is a silent, resentful contestation of colonial Western appropriation of the ‘exotic’. Two strong pieces thus engage with Paul Gauguin’s sensuous depictions of Polynesia. One is the Aotearoa/New Zealand pavilion, allocated to the Samoan Yuki Kihara’s installation “Paradise Camp”, in which the artist shows large scale photo-installations of fa’afafine – women-like men – and directly fustigates, in a video, the French artist in an imaginary post-colonial dialogue with him. Emma Talbot’s giant drawing on cloth also engages Gauguin, from whom it takes its title, “Where are we from? What are we? Where are we going?” This work questions what humanity is all about with painful questions.

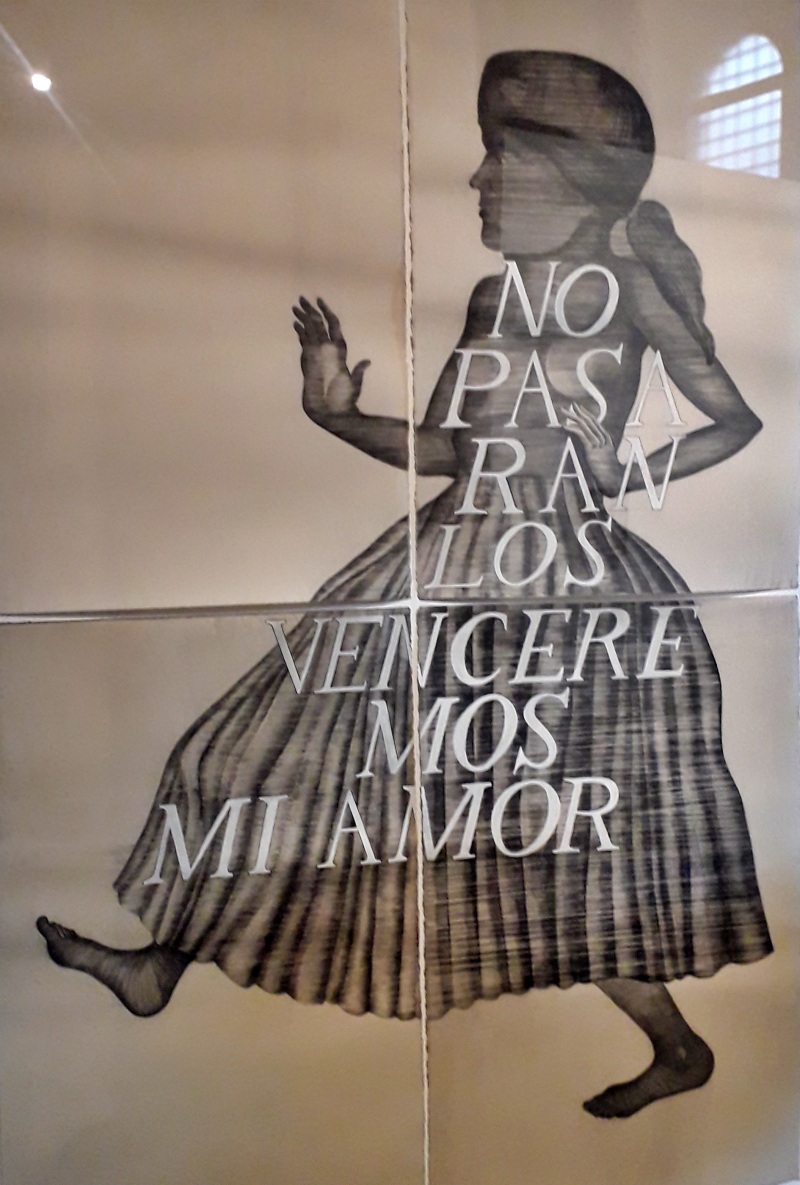

There was a lot of space for alternative narratives in this Biennale. Remarkable was also the Polish pavilion, which had been turned into a Roma pavilion by Joanna Warzsa; twelve giant tapestries organized according to the zodiac depict Roma legendary history and daily life in Poland. Angela Su’s video ‘The Magnificent Levitation Act of Lauren O’ describes the attempts at levitation of a circus artist drawn into the hopeless radical political struggles of the 20th century, and finding her way out of them by overcoming gravity.

My attention was drawn by the amount of painting on display, and the nearly complete absence of empty conceptual art, or the ‘research in progress’ kind of thumb-tack installations by contemporary artists who, it often seems, really have nothing to say (at least, not to me). In that regard, I loved the Albanian and Slovenian pavilions, of work by Lumturi Biloshmi and the Bosch-inspired paintings of Marko Jakse respectively. Noah Davis’ paintings of black Americans were another illuminating surprise, as well as Kenyan artist Paul Onditi’s recent work. Eritrean artist Ficre Ghebreyesus large-scale paintings are another attempt at ‘reappropriation’ of local stories from their Western interpretative frameworks.

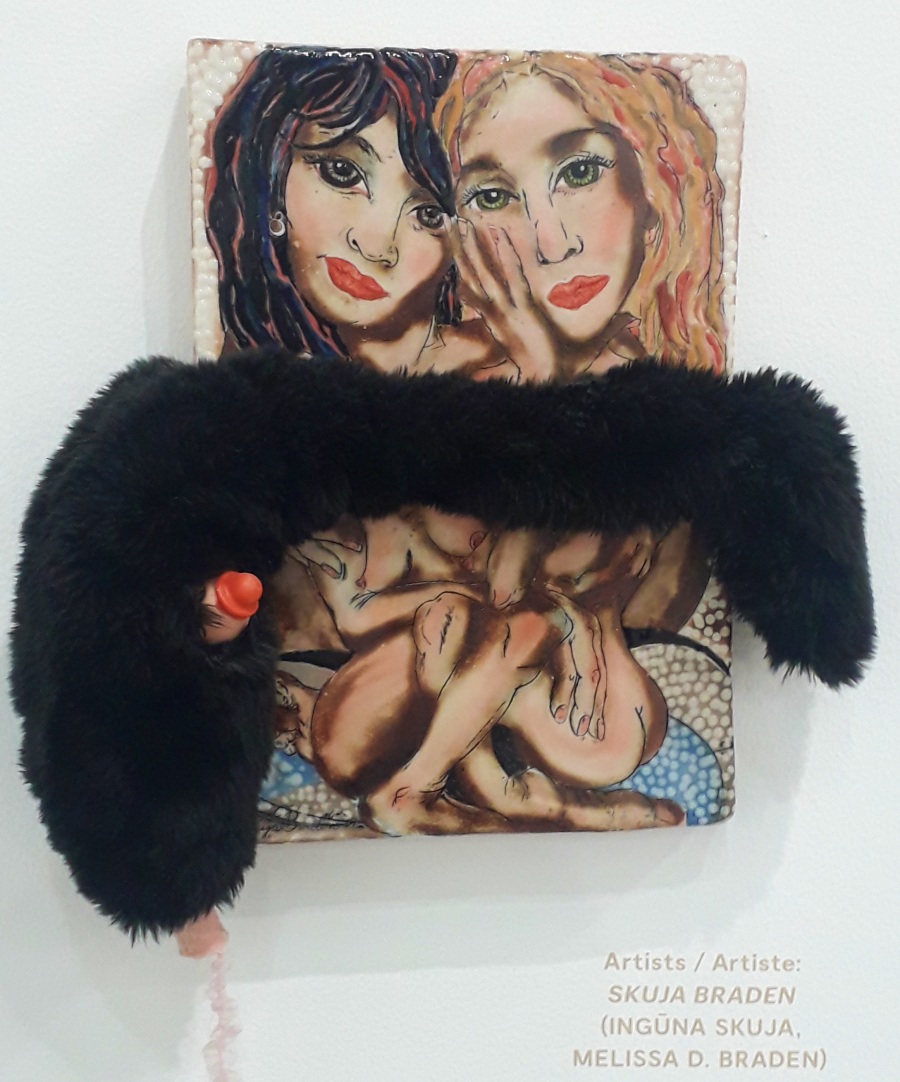

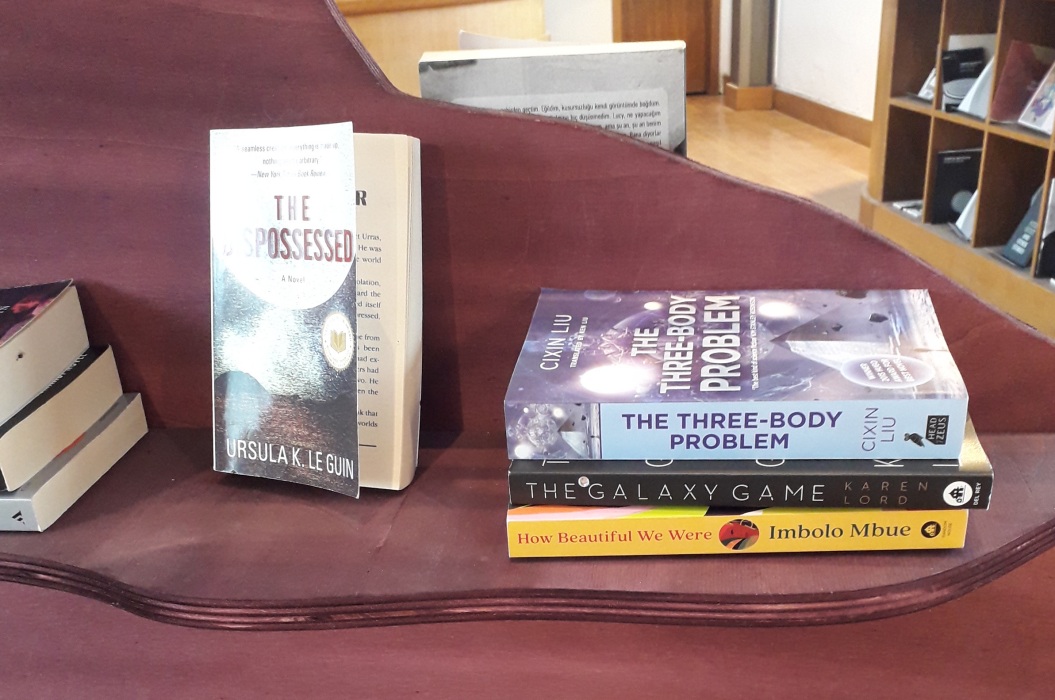

Nan Goldin’s strong and beautiful video ‘Sirens’ portrays the high, ecstatic side to the female body. I would have really liked to enter the video, become enchanted by the siren’s song and consumed alive. More playful is the artist duo Skuja Braden (Inguna Skuja & Melissa Braden) which have transformed the Latvian pavilion into a complete mess, casting both daily objects and their wildest, often erotic fantasies into ceramics which are littered all over the space; their show is called Selling Water by the River. A third show, among many, that touches on female power is the installation of science fiction books by female authors, part of a show by Müge Yilmaz called The Adventures of Umay Ixa Kayakizi in the bookstore of the Giardini; it is the lifework of a 25th century female astronaut that has investigated her historic predecessors and found them in authors such as Ursula Leguin and Cixin Liu, both of whom I happened to read last year.

I could go on about a few other artists that I really appreciated, but I think I have conveyed my main impressions of this truly inspiring Biennale so full of primal female energy… we will need much more of this to rebalance the male mess we have made of this world!