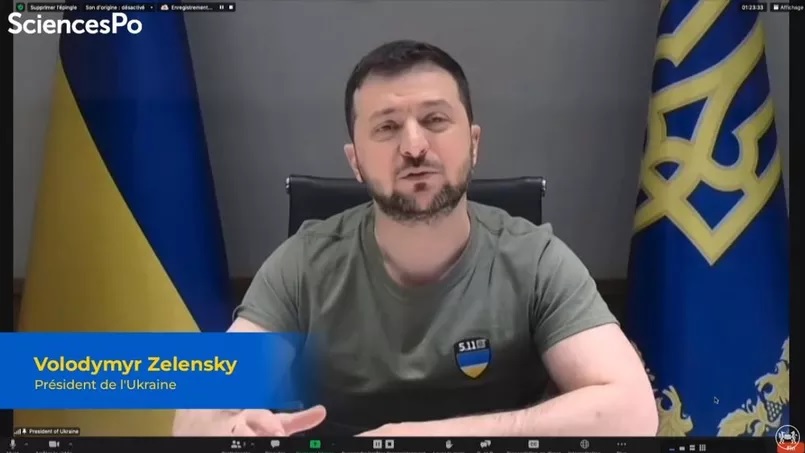

On 11 May, the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky spoke for one hour, through video connection, to the students of Sciences Po; students from other universities were also present. It appears to be the first time Zelensky addresses foreign students since the war began.

Noting that he had been briefed that at the end of his speech, five students would be allowed to ask a question, he said he found that a bit unfair towards other students, and that he preferred a dialogue. In his 15 minutes introductory speech, Zelensky asked a few pointed questions to the political science students:

- “How is it”, he asked, “that one person could decide on a war against a people, and cause thousands, potentially even millions of deaths? Even though nothing suggests the Russian people wanted this war”.

- About NATO, he asked how effective this defense treaty was. Ukraine had not been admitted earlier, in his opinion, because NATO chiefs were afraid their countries would be dragged into war under the Art. 5 collective security arrangement. “What if Russia attacks Lettonia next?” he asked. “You probably have never visited that beautiful country, maybe you have no connection at all to it”. Would NATO really risk going to war to defend Lettonia? What is the use of this alliance?

- He also asked about the European Union. “We [Ukrainians] are not only European, but we are also defending all the values Europe stands for” he reiterated a few times. “European societies are with us, there is no doubt; but Europe’s politicians are less supportive. They keep speaking about the future, but we are already living together. It is as when a couple is together, and one side keeps promising marriage to the other side, but not following up. After a while, the other’s trust starts eroding. What does that do to the relationship?”

- He asked a more general philosophical question. Russian troops have committed many crimes. They are not only fighting, but also raping, even children, in one case even a baby; beheading people, breaking their legs. Are they doing this by themselves, or under orders? In both cases, how can we even understand such actions? How should we deal with it, as humans?

- This led him to a question about international justice: where is it now, and how will it be obtained in the future?

- On a more personal note, he mentioned his daughter had objected to him becoming president, noticing it would change her life by making her a public persona too. Now his whole family was experiencing a much higher level of threat. Was this justifiable, he wondered, asking students how they would react if their father became president.

Only this last question was responded to, by the first student pre-selected to ask a question. He predictably said he would be proud if his father became president. Two other students addressed other questions, without really responding to them. The other five students (there was time for eight, in that Zelensky succeeded in opening up the floor a bit) stuck to their pre-planned questions.

I understand that the students may have felt out of their depth, and maybe they felt they had no legitimacy to engage the discussion with the President on his terms instead of those of Sciences Po. But I believe that Zelensky asked truly important questions, which political science students should think about deeply. He asked them not rhetorically, as an intellectual exercise, but from his position: in a war that is being fought right now, and which raises such questions.

Zelensky obviously focused on Russia, as he must. But his questions equally concern Western democracies. How could the UK, in 2003, agree to go to war alongside the USA in Iraq, although the vast majority of the British was against that war? What about the power of the US President to attack other countries? Why do collective security agreements not cover other countries, such as Syria, Libya, Yemen and Myanmar? After all, chapter 7 of the UN Charter also contains a commitment to collective security. Why is there no international justice to sanction such wars? Why do Western leaders that order the assassination of people abroad, and sometimes unleash wars that kill thousands of people, never face justice? (I thought of the veteran Al Jazeera journalist, Shireen Abu Akleh, who was assassinated by an Israeli sniper yesterday; how likely is it that the Israeli military will face any form of international sanction?) Where is the commitment of political leaders to the values and objectives of the societies they lead, and to the promises they have made? Thinking about the function of the politician, how do the personal and the political relate within a same person? All these issues were clearly implicit in the questions he asked of the French students, supposedly the future leaders of society.

The reaction of the students was polite, formal, and unimaginative. It is hard to discern any wind of change in this elite political institution. The institutional setting didn’t help. Only one student asked a more daring question: whether the threat deployed by Putin of using the nuclear weapon could lead to a nuclear disarmament in Europe. Zelensky strongly supported this, noting he had raised it with European leaders previously. When the leader of a nuclear power threatens using the nuclear weapon, he should already be sanctioned for that threat, he suggested. Yes, there should be nuclear disarmament in Europe. I saw a twinkle of uncertainty in his eyes. He must have been thinking: all will agree that Russia should be demilitarized, but will France and the UK accept nuclear disarmament?

I hope that not only the students, but also the direction at Sciences Po reorients its courses to address such important questions for the future.

The author has lectured at Sciences Po since 2010

“…I hope that not only the students, but also the direction at Sciences Po reorients its courses to address such important questions for the future”. That I hope too, but also to have more presidents, decision-makers and high-level players to come to speak of the big questions they are dealing with. Not only to have a top-down presentation on how great they are, but to show vulnerability by inviting people to think along (and to have the guts to act upon the reactions too).