A workshop will be held for all those interested in participating in this research project at the Downtown Campus (off Hamdan Street) of NYU Abu Dhabi on Tuesday 25 February, from 18:00 to 20:30.

For details about the workshop and registration see the bottom of this page.

Introduction to the research subject

- Stone Altar from Marib (5th – 4th Century BC) and Bronze Statuette of the warrior Ma’dikarib, South Arabia (6th century BC). These and all other photos and maps/diagrams on this page are reproduced from the book “Arabia and the Arabs from the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam’ by Robert Hoyland, 2001. See below for ordering information

“Only a small proportion of the lore of the Arabs has come down to you. Had it reached you in its entirety, much scientific and literary knowledge would have been yours”

This quote from Abu ‘Amr ibn al-‘Ala, who passed away in AD 770/ AH 154, (cited by Ibn Sallam Al Jumahi in Tahaqaat Fuhuul al-Shu’araa’, Cairo, 1974) is one of the few recognitions by Muslim authors of the value of ancient Arabia’s cultures.

Not only Muslim scholars, but also Western specialists of ‘Islamic Art’, usually maintain that Islamic culture owes little to the civilizations that thrived on the Arabian peninsula in the millenia before the advent of Islam. It is true that the pre-Islamic Arabian cultures had mostly exhausted themselves before the birth of the Prophet Muhammad, the tail end of their great legacy being smothered in the rivalry between Rome and Parthia. But there was also continuity between the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods on the Arabian peninsula: Islam and Arab culture were integrated smoothly, in most cases, by local cultures that were the inheritors of Dilmun, Saba, Kindah, the Nabataeans etc.

In fact, this dismissive attitude towards pre-Islamic Arabian culture seems mostly to be the result of ignorance. Although rapid progress is being made in our knowledge of ancient Arabia, thanks to archaeology and increased research supported by the GCC states, the amount of information about these cultures is still scant. The contemporary researcher is faced by beautiful but puzzling remnants of these civilizations.

The historical narrative of ancient Arabia is thus a largely unexplored patchwork of stories, or fragments of stories. While this may be problematic to the historian, it provides a fertile ground for artists.

From left to right: limestone funerary statuette from Bahrain, 2nd-3rd C AD / stone grave marker from Tayma region (NW Arabia) / Basalt stele depicting the goddess Allat fitted out like the Greek goddess Athena, from Kharaba in the Hawran, 2nd C Ad

There is little information about pre-Islamic Arabia in most school curricula, and thus most contemporary Arabians grow up with little knowledge about the cultures that thrived on the peninsula thousands of years ago. As a result there is not much presence of ancient Arabia in contemporary Arabian culture. This research proposes to turn the spotlight on this relatively unknown part of Arabian history. It is primarily an artistic research, but it seeks to embed itself within the academic knowledge of this topic, which fortunately is quite abundant in the Gulf states, particularly in the UAE. The research will be fully hosted on a dedicated website, which will soon appear online, and it will result in an online exhibition and a public presentation in the UAE.

This research project is supported by a fellowship of the Forming Intersections in Dialogue (FIND) programme hosted by New York University Abu Dhabi. FIND is an innovative cultural laboratory that forms intersections and dialogues between artists, writers, scholars, designers, technologists and the UAE landscape in both a historical and contemporary context. Through the production of art, stories, scholarship, workshops, and analogue and digital initiatives, FIND engages Emiratis, UAE residents, and the world with reflections of the UAE (extract from the FIND website).

Artistic scope of the research

There are many ways in which an artist could approach this subject. One is by studying the material remnants of ancient Arabian cultures: statues, rock art, architecture, ornaments and archaeological objects and giving them a new expression in contemporary art. A few interesting examples of this material culture can be found on this page.

Another is by studying immaterial culture: in the history of this period an artist may find interesting parallels to contemporary perspectives on Arabia. For example, ancient Arabia was at once secluded – a territory unknown to outsiders – and well integrated into the trade networks linking India, Iran, Mesopotamia, Egypt and the Mediterranean. Another parallel: Arabia was famed and envied for its riches, which made foreign chroniclers fantasize about palaces lined with silver and gold.

There are many interesting myths about this era; one could be inspired by accounts of winged snakes (as told by Herodotus) that guarded the frankincense trees that provided so much wealth to Arabia; or investigate the mythical mines of King Solomon, which also financed part of the initial expansion of Islam; or again, study the complicated relations between Christians and Jews on both sides of the Red Sea, that led to the massacre at Al Ukhdood (Najran).

Closer to the UAE are the mines of Magan, that provided the classical world with copper since the bronze age – why not use this copper in art? Or could something be done with the abundant detritus produced by copper mining? The UAE itself hosted some of the largest and wealthiest settlements of the peninsula – how is that presented nowadays, in museums? Then again, archaeologists have deduced building types from uncovered vestiges. All this could also be fertile material for artists.

There is thus no set approach to how artists could be inspired by ancient Arabia; the purpose of this research project is to open up this domain for artists, and start a public dialogue on the subject of possible parallels, or even continuity, between the ages.

If you want to register for this research project, either as candidate to participate in the team, or as an external participant, please send an e-mail to me (robert@gulfartguide.com) and cc my research assistant Amal Bssiss (amal.bssiss@gmail.com) and our anchor at FIND, Alaa Edris (alaa.edris@nyu.edu).

Note: travel and (up to a point) research and artistic production expenses for the team members (not the external participants) will be paid for from the research budget.

For preliminary reading I strongly suggest the book “Arabia and the Arabs from the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam‘ by Robert Hoyland, Routledge, 2001. All the images and quotes on this page come from this book, and I am heavily indebted to the author for my scant knowledge on the topic – just enough to fire the imagination.

It is available, also on Kindle, on link to amazon.com here.

Thank you for your interest!

- Representations of Arabs from the Sinai and from the Gulf coast, on a stele produced during the reign of Darius for Egyptians (whence the hieroglyphs)

- Alabaster female bust found outside Timna, modern Yemen, 1st C AD

- Relief on the lintel of the portal of a temple at Haram, drawn by David Hopkins. Evidence of geometrical patterns later used in Islamic art?

- Assyrian bas-relief depicting Arabs, from Niniveh

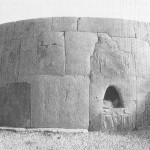

- The great Hili tomb, reconstructed, Al Ain 2500 to 2000 BC

- Nabataean tomb facade from Hegra, 63 AD

- Alabaster funerary stele showing the deceased engaged in a feast (top) and camel raiding (bottom).

Very interested in this research project, though passively.

I spent eight years in Saudi Arabia and the Levant, working as a geologist and extensively traveling through the region to satisfy my archeological and historical curiosity.

While mapping in the north of KSA from 1980 to 1983, using a helicopter, I discovered many neolithic sites in the great Harrat that continues into Jordan, as well as at least one Nabatean village/town west of Wadi Sirhan in the desert near the Jordanian border.

This knowledge was lost because of various reasons.

I would suggest that high-resolution satellite-image mapping of this Saudi Arabian region, roughly between the Jordan and Iraqi borders in the north, Sakaka-Jawf in the south and the TAP line in the east, might yield quite interesting results, which could be followed up in the field at a later stage.

Wadi Sirhan was an important route connecting eastern Saudi Arabia and the Gulf coast with Egypt and the Levant. Any artist interested in picking up this suggestion by my father?