African Arguments published a short version of this article with a focus on the UN, and a similar, slightly improved version of this article appeared on democracyinafrica.org,

On October 25, 2020, Somaliland authorities suspended their relations with the United Nations and banned its activities ‘until further notice’. While the frustration of the thirty-year old unrecognized state with the UN can easily be understood, this move is unlikely to bring any benefit to the country. Somaliland is gradually developing into a clan-based autocracy. President Bihi maintains a balance among the ruling elites by granting and revoking business licenses and political positions, but this clientelist system produces little economic growth and offers no scope for political renewal. The youth is increasingly disaffected. The President instead blames the country’s problems on the lack of direct access to international funding and is increasing the pressure on the international community.

One week earlier, on October 17, the cabinet of Somaliland’s President Muse Bihi decided not to restore the landing rights for direct flights from the unrecognized state’s capital Hargeisa to Dubai by Air Arabia and Fly Dubai, citing legal difficulties. The details of the underlying conflict provide a clear window into Somaliland’s politics and how they affect, and are affected by, clan and business interests.

Businessmen belonging to the Habar Je’lo clan obtained licenses to operate flights with these low-cost carriers between Dubai and Hargeisa in the times of their kinsman President Siilaanyo (2010-2017). In April 2020, the current President revoked the license of both operators, claiming they were illegal. Since then all travellers to Dubai and beyond must fly with Ethiopian Airlines through Addis Ababa – a much longer and more expensive flight. A Somaliland newspaper calculated that the Ethiopian carrier had raised the average price of a ticket to Istanbul from 530 to 970 USD over the past six months. This has damaged many small traders that thrived on the direct and relatively cheap flights to and through Dubai.

The Habar Je’lo are one of the big clans of the Isaaq clan family that forms an absolute majority of Somaliland’s population and whose elites rule the country. Some of its most powerful members were long allied to prominent Sa’ad Muse leaders (another large clan of the Isaaq family), and they are considered to have helped the Sa’ad Muse candidate Bihi win the 2017 elections. But today many Habar Je’lo feel they are being squeezed from positions of political and economic power. They have less powerful ministries than they believe is their share, and their businessmen have been hindered in many ways, typically by revoking licenses or not approving them.

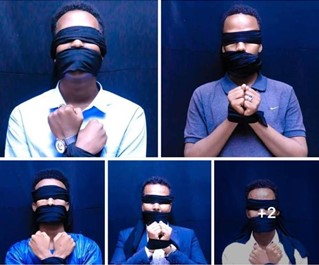

The decision to revoke the licenses of Fly Dubai and Air Arabia was taken up by Habar Je’lo clan elders, who, led by one of their Sultans, petitioned the President. The President shielded behind his cabinet – though he usually takes all decisions by himself – and the Minister of Aviation then decided, probably under pressure from President Bihi, that the licenses could not be restored. One of the President’s nephews manages the country office of Ethiopian Airlines, which today has a near monopoly on international flights. The clan elders have seen this as an affront to their dignity. The undiplomatic attitude of the President, and the rapid accrual of economic power in the hands of his family and closest allies, are causing resentment, even among the President’s closest allies. Protests met the President’s vehicle caravan as it toured the Togdheer region on October 18 and 19. The images below were shared on social media with the caption “Mr President, we welcome you to the Togdheer region with our hands and eyes bound” and a poem starting with “I did not say ‘stay with me’ / I did not welcome him”.

Quest for recognition or money?

The reason given for revoking the operating licenses of the two Gulf-based carriers was that they were taking orders from Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia. Somaliland declared its independence from Somalia in 1991 and its people developed a functioning state based on a constitution and multiparty elections. While the parent country was engulfed in piracy, terrorism and more conflict, Somaliland experienced peace and stability. But it was never recognized by the international community. Thus, when Mogadishu ordered the Dubai-based carriers to cease their flights to Hargeisa because of coronavirus restrictions, the airlines decided to obey, to the fury of Somaliland’s government.

Somaliland’s quest for recognition has had no results, but the country is accepted de facto. The UN, other international organizations and individual countries and their development agencies increasingly support the government. At least 50% of the government’s expenses are covered by international support, and probably much more. The signboards of most ministries and government institutions are flanked by the logos of UN and donor agencies and international NGOs.

But this is not sufficient. In September 2020, the government of Somaliland issued a decree banning events by international organizations that use the emblems of the federal government of Somalia. On October 17, the cabinet expressed its anger at a Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework also covering Somaliland, that was signed between the UN and the Federal Government. On October 19, the Ministry of Planning announced that it would critically review all UN and NGO projects, to determine if they align with the National Development Plan. The decision to suspend relations with the UN is a repeat of 1994, when President Egal expelled the UN because of its efforts to undermine Somaliland’s independence and meddle in its internal politics.

But the decision also reflects confidence that the UN will continue funding the Somaliland government. In a dynamic difficult to understand for outsiders, aid recipient countries know they can apply pressure on donors, who appear to need to disburse funds as badly, or even more, than the beneficiary country needs them. In January 2019, the Federal Government of Somalia, which depends on the political and economic UN for its survival, nevertheless expelled the UN Special Representative Nicholas Haysom because he had criticized the government’s decision to remove the main contender for a regional election by force. In 2018 a UN agency was expelled from Somaliland, reportedly because it refused to build two houses for ministers. Its office relocated to Garowe, the capital of Puntland, and continued its operations in Somaliland through its local partners until it was readmitted in 2019.

The absence of international UN staff would not be noticed, as they are locked by their own security behind high walls, rarely coming out (the UN applies the same ‘code red’ security standard to Somaliland as to the rest of Somalia, despite Somaliland being one of the safest countries in Africa). UN support may benefit the top tier of the civil service and of the contracting economy, but the impact of the organizations’ activities on the country’s population is minimal, according to any Somalilander asked. A 2019 grant of 7,500,000€ by the EU to UN Habitat to develop Somaliland’s main port of Berbera has not seen its first disbursement yet. Somaliland’s authorities argue that the hefty overheads paid to inefficient UN agencies would be better spent if the government could spend these funds itself.

President Bihi has repeatedly expressed his discontent at not being able to access international funding directly. The clearance by the IMF and World Bank of Somalia’s debts earlier in March 2020 makes the federal government again eligible to borrow on international markets, leaving Somaliland at a disadvantage. While ostentatiously still seeking international recognition, there is no strategy to achieve that goal, and Bihi’s sights seem instead firmly set on access to funding instead. The recent diplomatic alliance with Taiwan, recently analysed in Democracy in Africa as a strategic move by Somaliland authorities, is already in jeopardy as Taiwan’s press is providing increasingly critical coverage of internal developments in Somaliland.

Autocracy

However, the government’s capacity to handle funding is seriously deficient. Corruption–fuelled mainly by international assistance–has become blatant, with government officials acquiring prime real estate property in Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. The Rule of Law is weak: the Judiciary is wholly subservient to the Executive and rarely prosecutes even the most evidently corrupt officials. There have been no legislative elections since 2005 and the upper house of parliament (the Guurti) consists of pro-Government clan-representatives that were appointed in the 1990s. The executive can thus act without any oversight or constraint on its actions.

In the ruling Kulmiye Party, President Muse Bihi has grabbed full power in a recent party congress, keeping the chairmanship despite his presidency and eliminating all rivals. As to the opposition parties, they have discredited themselves by lack of any concerted opposition and notoriously corrupt behaviour. Every ten years, the political landscape is renewed by the formation of new political parties (only three are allowed by the Constitution) through local council elections, but there is serious doubt whether this will happen as scheduled in 2021.

In short, Muse Bihi has succeeded in concentrating power in his hands and has made it exceedingly difficult for any contestation to emerge. The discontent of Habar Je’lo clan lineages referred to above will be bought off with a few judiciously allocated contracts and appointments. This ‘traditional’ political wheeling and dealing has maintained stability over the past decades, but its benefits to wider society are declining.

Hargeisa provides a case in point. Despite considerable taxes paid by its businesses and residents, and hundreds of millions of dollars in yearly development assistance, hardly a road has been paved in the capital during the past five years. There is still no running water in most of the city, the waterways and green spaces are clogged with plastic litter, and public facilities such as health and education survive only because of NGO support. Meanwhile city officials build mansions and drive around in expensive four-wheel-drive vehicles.

Bihi gambles that, if the UN caves in to pressure and his government manages to access international funding, it will allow the government to buy the support of more groups (with the debt to be paid back by future generations). He also knows that Western intelligence and security forces, who maintain a discrete but strong presence in the country, back him; his strong anti-terrorist stance reassure them. Publicly, economic and development problems are continuously blamed on the lack of international recognition, to the point that residents—when commenting on potholes in the main streets—joke that they cannot be filled until their country is recognized.

Options for Somaliland’s Youth

The burgeoning educated, mostly unemployed, young urban class no longer expects its situation to improve, even if the government becomes flush with donor money. The labour market seems to be stagnating. They are finding jobs in Mogadishu, where there is a growing demand for skilled labour not easily found in South Central Somalia. Somalilanders are also offered positions in the federal government, which is intent on keeping up the semblance that it also governs Somaliland.

An ambitious university lecturer in Hargeisa, seeing his chances for development stunted by clan politics in Somaliland, left for Mogadishu where he created a political party advocating unity between the two countries. On October 20, he was appointed Minister of Information, Culture and Tourism of the Federal Government. Such examples of a successful career move is encouraging other young Somalilanders to try their chances in Mogadishu.

Such people are considered traitors by the Somaliland government, and young Somalilanders returning from Mogadishu are routinely interrogated by Somaliland intelligence upon arrival. Questioning the independent status of Somaliland and advocating unity are seen as high treason, an accusation frequently levelled at opponents. Among the educated youth, however, the desire of normalizing relations with federal Somalia is growing.

Other young Somalilanders choose to emigrate, either the hard way–with people smugglers via Ethiopia to Libya–or the better way, e.g. with a scholarship to Turkey. There are also those who choose to remain and struggle despite the lack of opportunities for change and growth. Despite the increasingly negative climate, levels of repression are low. Clan solidarity continues to operate also for those with less access to power. Youth opposition leaders may be harassed, but they are not tortured or killed.

There are also those, of course, who do find jobs in Somaliland’s businesses or in the civil service, or again in the NGO sector that benefits from international funding. Youth educated in Islamic schools and universities are particularly successful. Like their models from the Gulf countries, they are socially conservative, politically quietist and economically successful, characteristics appreciated by their employers, typically large telecoms, banking and trade corporations. This is not a novel phenomenon. Gulf countries’ efforts to influence education, social and religious practices have gradually changed Somaliland’s cultural values since the 1990s.

Most of Somaliland’s youth follows a strict Sunni version of Islam: non-violent Salafism. ‘Vice-and-virtue’ style community policing is increasingly accepted by society and the authorities, but the main vector of influence is social media. More secular-minded youths find that this discourages freedom of expression and cultural renewal; more so than government policies that maintain a secular outlook despite the quiet erosion by these same religious values. At the recent inauguration of a new Islamic bank in Hargeisa’s centre, the leader of Somaliland’s main women’s organization was asked to sit at the back and the traditional dances were cancelled, but when the religious leaders present demanded that Somaliland’s national anthem be performed without music, government representatives objected.

The Islamic and the secular youth share their criticism of corruption, the inefficiency of the government and the lack of development. Criticism of the authorities is widespread but not publicly expressed, because the government spins all criticism of it into an ‘anti-Somaliland’ discourse. In this environment, public debate about where Somaliland is heading is stifled. Therefore, though the concentration of power seems to practically assure Bihi of an electoral victory in the next presidential elections (2022) it is really not known how the population of Somaliland will react to the unfolding crisis between their national authorities and the international community.

Xxx