Perspectives from Khartoum, March-April 2022

I have come to Khartoum for a cultural mapping. The European Union has decided to expand its support of the Sudanese cultural sector. The EU, wired to support the state of Sudan, has no partner to work with since the military coup of Oct 25, five months ago: it does not recognize the military government. After several months of efforts to help reconstitute a civilian government, the EU delegation in Sudan has decided to increase its assistance program towards the support of civil society. One of the components of civil society is the cultural sector, supported over the past years through EUNIC. I am glad that sometimes the European Union does use its money wisely. My goal is to help them invest strategically into the cultural sector, in a way that builds it up instead of making it dependent on external funding.

As a result I’m in an intense round of consultations with all kinds of actors in this sector. Artists, directors of private organizations, commercial or non-benefit, institutions, researchers… everybody is speaking about the political and economic crisis, and are thinking about what the cultural sector can do to contribute to an outcome. In the following I will present some of their views on the double failure of the state and the economy, and how they are reacting to this crisis now. But first an explanation about the current situation in Sudan.

Background: the Sudanese Revolution

A popular revolt erupted in December 2018, caused by the increasing cost of living and a general exasperation with the political class. Omar el Bashir had been president since a coup in 1989, establishing a military Islamist regime that soon became a pariah state of the international community. After the start of the War on Terror he shifted sides and gradually transformed his regime into a neoliberal mafia-state run by members of the ruling party, the military, and their business interests. He allowed South Sudan to secede in 2011. This eased the international sanctions that had crippled the Sudanese economy since the mid 1990s and allowed the rapid integration of Sudan into global markets. But the general public benefited little from the resulting boom. To the contrary, to access IMF loans the government lifted subsidies on basic foodstuffs and fuel, which deepened economic misery. Meanwhile the Sudanese population had been coaxed into the rushed lifestyle of the citizen of the global economy, away from a pretty relaxed lifestyle throughout history. Everybody was now ‘running for money’ but there wasn’t much of it around. The ruling elites were offering no perspective of a solution; they were doing fine themselves.

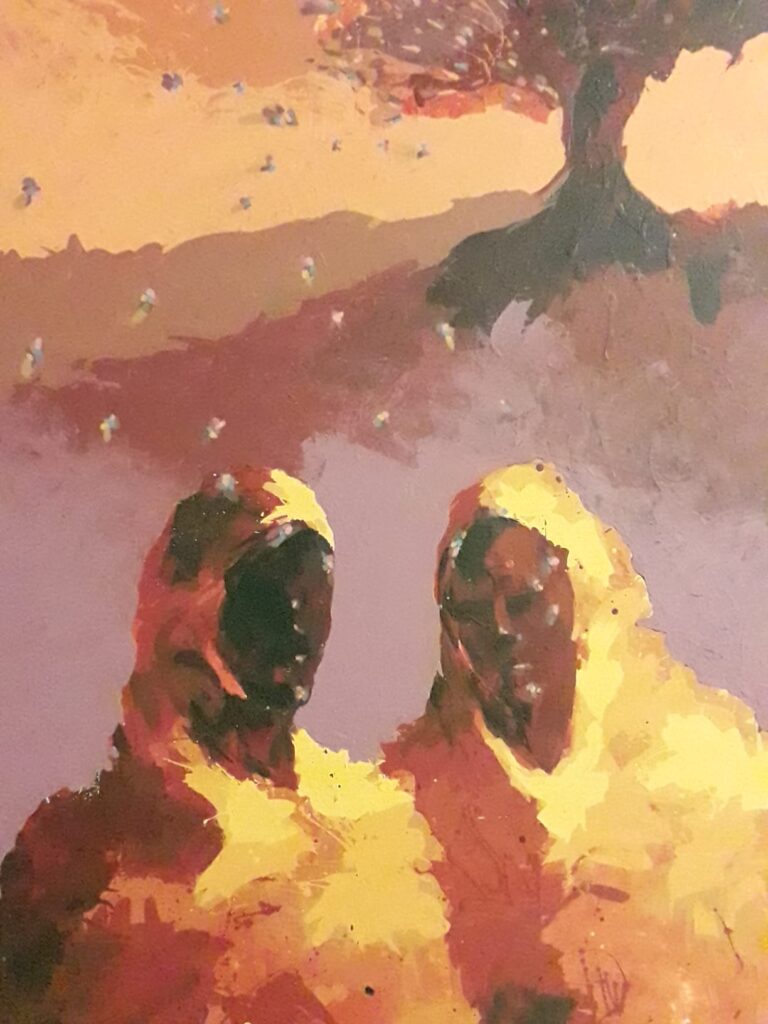

The public protests took the form of demonstrations and sit-ins before government buildings, of which some lasted months. They were expressly non-violent. During the mass demonstrations people found each other, helping one another in many ways. Artists played a major role in these protests, painting murals, making music, organizing theatre and other workshops. Protests in each neighbourhood in the city and in many other towns of Sudan were coordinated by ‘resistance committees’, local self-help organizations which had started forming years earlier. To the frustration of would-be mediators, there were no leaders of the revolution to speak with. The Sudanese Professionals Association and other civic groups leading the protests eventually came together with some opposition parties in the ‘Forces for Freedom and Change’ (FFC), but even here leadership was diffuse.

After nearly four months of continuous protests, on 11 April 2019 the military removed Omar el Bashir and established a Transitional Military Council (TMC) to ‘restore order’ and ‘prepare elections’. However the protests did not cease, despite rising levels of violence by the armed forces. On 3 June they violently dispersed the sit-ins, killing 128 non-violent protestors and raping 70 women according to one account. Still the protests did not cease. The main claim of the protestors was that the military should give up power immediately to a civilian government.

This happened in July 2019, when the TMC agreed on a transitional plan with the FFC. This was to be led by a ‘Sovereignty Council’ dominated by General Burhan and a civilian government led by Abdalla Hamdok. Fundamental changes in the regime did not take place but since the summer of 2019 there was a hopeful stability, monitored and supported by the international community. On 25 October 2021, weeks before the Sovereignty Council was also to be transferred to civilian rule, for the preparation of elections to be held in August 2022, the military ousted Hamdok in a coup, imprisoning some of the civilian leaders and retrieving full power over the state.

This has immediately been met by renewed protests in the streets. Faced with harsher repression by the armed forces, the joyful sit-ins and leisurely public demonstrations where entire families participated, which characterized the first phase of the Sudanese Revolution, no longer take place. The contribution by artists is now in helping lead the protests, and several have been killed for it when police shoots at demonstrators with lethal ammunition. The military rules the country but does not govern it, and is not recognized by its population. Even the political forces which could share in a new power deal are showing little interest in negotiating, and the African Union, United Nations, USA and European Union are giving up hope after five months of useless mediation efforts.

Foreign governments have isolated Sudan diplomatically and financially, although those of the Gulf, Egypt, Russia and a few others have been generally sympathetic towards Sudan’s armed forces. Russia’s Wagner group, for example, has reportedly become involved in the export of Sudan’s gold (a major export earner) most certainly in exchange for support to the security forces. Hemeti, the other leader of the military junta (he leads the Rapid Support Forces which committed countless crimes against civilians in Darfur, and now against demonstrators), just returned from meetings in Moscow in defiance of the international rejection of Putin’s regime. Whether he succeeded in obtaining extended support for Sudan’s ruling military clique is unclear. The economic situation is dire, with rapidly rising inflation and the perspective of a total collapse of the economy.

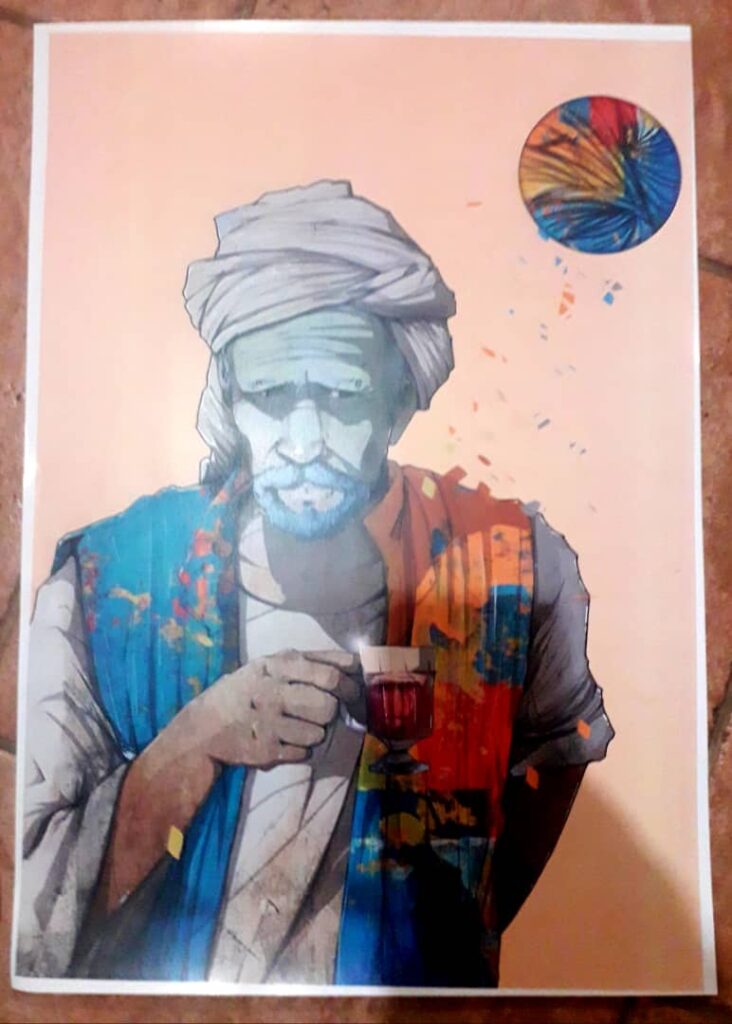

Artists impressions

This is the situation in which I am now in Khartoum. The situation is safe; we can move around town freely. We avoid demonstrations, which are always announced in advance. The Army, with the support of its foreign backers, is increasing its control over the media, including social media, but with the streets firmly opposed to its rule, people speak freely about the situation in the country. Although some resistance leaders are targeted by security forces (a new technique is kidnapping civilian opposition figures, especially women) I have not sensed personal fear.

I am having my meetings with Randa, a senior Sudanese cultural specialist and activist who has organized my visit, and two of her collaborators: Mustafa and Jassour. We have met with more than thirty people of the cultural sector over the past few days, ranging from individual artists to directors of cultural innovation hubs, and from fashion and handicrafts researchers to heads of cultural institutions. I will keep our recommendations for EU cultural support policies to those who asked for them, and reflect here on the sociopolitical situation. Given the chaotic situation, I have found surprising unanimity on the following points:

1/ The military coup of last October has stopped nearly all hopeful developments and forward-looking activities that were taking place under the transitional government; developments and activities which had literally exploded after thirty years of repressive rule by the previous regime. Only a few cultural entrepreneurs continue their positive, social change-oriented activities.

2/ There is no confidence any more in any kind of political power. None of the opposition parties are trusted. It is clear to all people interviewed that they do not expect any solution to come ‘from above’. They believe that the people of Sudan must come up with a solution in the form of a new government. But they have no clue how to make this happen. While the resistance committees manage local affairs, any form of coordination is made difficult by the distrust of politics. Society is only united in its rejection of the current government and the entire ruling system.

3/ The economic crisis (prices rise almost daily) is putting additional pressure on the population; this makes the search for a solution all the more urgent while making collective action more difficult as people tend to pursue personal survival strategies. These include emigration, searching for one of the well-paid jobs which still exist in the private sector or for funding by one of the foreign organizations still working in Sudan. But due to instability the latter have become rare.

4/ People consider the policies of the international community ineffective; they are rarely spoken about. The aura of the USA is (since long) on the decline, but all hopes remain pinned on the emergence of a European-type civilian government, hopefully with European support. But they see little movement in that direction.

The Sudanese revolution saw equal amounts of women and men, and people from all parts of the country, take to the streets.

5/ There is a strong sense that the young generation is fundamentally different from the previous one. Efforts by elder people to cling on to power, also in the cultural sector, are seen as one of the main obstacles to change. Values have changed: traditional internal racism (Sudan is composed of many African populations but dominated since centuries by the Arab majority) is rejected; gender equality is expected by young men and women alike; as well as equality of digital access and economic opportunities between Sudan’s different regions. Religion has no political traction.

6/ The cultural sector has an important role to play in envisioning a new future for Sudan. Without such an image it will be difficult to federate the population of Sudan around a new project. Although artists and creative activists may not feel qualified for it, they feel called into formulating such a vision.

Sudan in the global context

The situation in which Sudan finds itself is reminiscent in many ways of the double failure of state and economy in Lebanon and Iraq. In these countries, too, this double failure has led to a social revolt without perspective, because There Is No Alternative. But this happens not only in the Arab world; in South America too, popular revolts have taken place against the political-economic system, for example in Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina and Chile. In all these countries states have followed the neoliberal reforms imposed by the international financial institutions. While local elites connected to the state and transnational business interests are integrated into a global elite and sees their wealth and opportunities rapidly increasing, the rest of the population finds itself in a stagnant economy where social safety nets are being dismantled to deliver each person to the mercy of the market, in the process disintegrating society.

Sudan had well-functioning public services until the 1980s. Under the Bashir regime they stagnated and were politicized, and then gradually dismantled as the regime started implementing neoliberal reforms. Today, university professors earn less than 100 $ per month, and doctors in public hospitals are paid even less. No wonder they all turn to the private sector, establishing private universities and clinics. Sending your children to public schools is condemning them to no future, but private schools cost at least a few thousand dollars per year per child, money which few Sudanese have.

Another development has been the introduction of commercial agriculture, again with World Bank and other international development funding from the 2000s onward. Commercial agriculture allows a state to earn foreign currency (when global markets are good); moreover it allows ruling elites to increase their wealth by directing investments and reaping their rewards, together with foreign partners. The latter additionally earn money because commercial farming is input-intensive, meaning the increased use of fertilizers, pesticides and agricultural machinery, all imported. Local farmers induced to engage in commercial farming are usually offered cheap loans to buy these inputs, indebting them and thus reducing their independence. An added advantage from a macroeconomic point of view is GDP growth: while subsistence farming doesn’t register in economic indicators, commercial farming does. GDP growth in turn encourages foreign investment, fueling more economic growth (in mining, increased commercial agriculture, privatization of public utilities etc) which consolidates the power of the ruling elites and their global capital partners over the economy.

Meanwhile, commercial agricultural development, besides causing environmental damage and landing indebted farmers in jail when global recession cut their export opportunities, led to a mass rural exodus towards Khartoum, the hub of globalized Sudanese economy. The city’s population has doubled in the past decades. But the rural migrants could not find the jobs they had hoped for, and found themselves marginalized in a secondary economy. These formed the masses that came to the streets after December 2018, causing the Sudanese revolution.

These developments are by no means unique to Sudan. This has been happening throughout most of the developing world. Indeed, cutting public spending, dismantling barriers to ‘free markets’ and encouraging markets to take over the public sector and the domestic economy is the recipe which the IMF and the World Bank have been imposing in return for new loans since the 1980s.

One may wonder why countries accept these neoliberal policies that impoverish their populations. For one, there is no alternative political or economic system in the world to the neoliberal model. Second, it has become just as difficult for countries to avoid debt as for individuals in Western countries. It appears there is one country in the world that has no public debt, and that is Norway (another one is Somaliland, but only because the country is not recognized as one). All other countries are heavily and increasingly indebted. But third, and most importantly, loans accrue to ruling elites (they are never given to the people of a country, only to its governments) while debts must be paid by the public (through taxes, increased workloads, and the sale of their resources on the global market). So why would ruling elites that control governments not take loans?

It must be noted in passing that this vicious system, spurred on by the voracity of global capital, is what is causing global environmental collapse. It is indeed becoming obvious that there is no alternative to global environmental collapse as it is so intricately linked to the global political economic system; unless that system is thoroughly reformed.

The revolutionary social movements that are appearing in more and more countries are a nearly organic reaction of society to social disintegration. They reaffirm the primacy of the social over the political-economic model which destroys society and its natural environment. Invariably, participants in these social movements have experienced joy and a collective sense of purpose when taking to the streets; they are also accompanied by a cultural flourishing at a popular level. At least, until they meet with repression by armed forces.

The future of Sudan’s military regime

This brings us back to Sudan. What sets it apart from Iraq, Lebanon and the South American countries mentioned is the military coup. As I am writing this, I just witnessed the Sudanese armed forces rushing to quell a demonstration. Our car was pushed to the side of the street as about twenty jeeps and five trucks full of heavily armed soldiers or military police stormed by. The gunmen were cheering wildly, as if they were going to a party. Obviously, being able to beat up and shoot unarmed demonstrators seemed a joyful prospect to them. As far as I know, Sudanese revolutionaries have never so much as thrown a stone at the armed forces, trying instead to convince them that they are part of the people.

Military coups, and military rule over societies more generally, are still seen as illegitimate in our world. It may be changing. Israel has consequently supported autocratic regimes in the Arab world, inspired by a fear of Arab populations, political Islam and a confidence that by selling security technology to friendly autocratic regimes they can keep them under control. They are reportedly doing this in Sudan too, supporting Hemeti. This explains why the USA and, more reluctantly, the EU have supported the same military regimes (to do otherwise might appear ‘anti-semitic’) and why the Arab world seems so hopelessly mired in autocracy. When the Egyptian military overthrew the elected government of Mohamed Morsi in 2013, the West accepted it, because Morsi was from the Muslim Brotherhood and Israel feared him. Sudan is different, because its military regime was earlier Islamist, ‘terrorist’ and criminal (Omar el Bashir awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court); besides, there is no political Islam in Sudan to fear. The EU’s engagement to support the transitional regime in Sudan was genuine, and generously funded. EU officials in Khartoum seem as upset by the military coup as most Sudanese.

Because the international community condemns the coup and no country has so far recognized the legitimacy of the military regime, the Sudanese revolutionary movement can still count on the sympathy of the EU, the USA and the UN. But the Sudanese streets have no expectation that this sympathy will lead to the overthrow of the military; at most it will cause the slow attrition and crumbling of their regime.

In the meanwhile, as a European ambassador pointed out to me today, the military junta makes no effort to govern the country. They simply rule. The coup was carefully planned, but not what was to happen after the coup. The institutions of government have no clue what they must do and have mostly reverted to how they functioned before the Sudanese revolution. The security forces are reflexively applying their tools of social control, compiling information on each citizen and foreign visitor, now also applying sophisticated digital tracking with technology provided from abroad. But they don’t know who they should target, who to repress besides demonstrators. There is no plan. The junta seems to be waiting for civilian forces to approach it again for a power-sharing agreement, but no civilian forces with any traction on the streets are forthcoming.

What seems most likely to happen is that the ongoing economic collapse will plunge the country into a deep economic recession. By selling Sudan’s gold and other natural resources to friendly countries, the military may continue to earn enough to pay the armed forces decent salaries, but the soldiers will have family members suffering from increased poverty, maybe even hunger, putting their loyalty to test. The business elites connected to the state and the armed forces will thin out, leading many of them to emigrate and oppose the military from abroad. Meanwhile the population will either seek to emigrate or turn to local self-help systems such as those organised by the resistance committees (which the military would be ill-advised to dismantle) leading to parallel systems of authority in the country, one ruling, the other self-governing. Eventually, contestation will arise from within the armed forces and a new transition to civilian rule will be possible. The question is then whether practices of self-governance will have matured sufficiently, as political institutions, to provide a new basis for a civilian government.

The alternative: self-governance

In January 2022 the resistance committees of Khartoum state (the urban agglomeration of Khartoum, which may hold up to half of Sudan’s population) published a Charter for the Establishment of People’s Authority. This charter is an open source document, and it leaves most specifics of the transitional governance structures open to be decided in a democratic way. But some of its principles reveal what self-governance coordinated by resistance committees may look like:

– Federalism: “the transfer of central state powers to the regional and local government levels” (p6).

– “Radically changing the governance system and policies in the country in a way that allows the participation of local communities in decision-making, in the formulation of public policies, participation in their implementation and oversight over it, in a way that establishes values of participation, accountability, transparency, and sharing, as well as all the values of good governance, in a manner that contributes to resolving the historical impasse regarding the relations between the state apparatus and the local communities; so that the process of governance becomes a strategy for a societal transformation in its political and economic aspects, founded on positive cooperation between the state and society, in accordance with the reality of the political, cultural and social idiosyncrasies of Sudanese societies”. This sentence is long and unwieldy but worth quoting in its entirety (p6).

– a firm commitment to transitional justice to resolve all crimes of the past and ensure that no future crimes against the Sudanese people take place.

– the establishment of a national peace conference and a review of the separate peace agreements established in the past years which did not involve the stakeholders (the population).

– a comprehensive reform and restructuring of the entire security sector, bringing it under civilian administration.

– reforming the justice system to allow its independence through internal democratic processes and the establishment of the Rule of Law.

– depoliticizing the civil service and introducing internal democracy and notions of professionalism and merit-based appointment; enabling the civil service to exercise good governance.

– reviving the trade unions for democratic control of the key sectors of the economy, including the formulation of public policies that “break the governance structures of the post-colonial state” (p9).

– rebuilding the social welfare state in the domains of health and education.

– devising a plan for national economic revival that includes renegotiating debt with foreign financial institutions; “plans that consider the equitable distribution of wealth, power, transparent management of public resources, and protection of the environment and local workforce”.

– restoring financial rigor, dismantling the hold of the military on the economy, reviewing all financial agreements since the Bashir coup (1989), systemically combating corruption and recovering all stolen, looted and diverted public assets

– reviewing Sudan’s foreign policy, settling conflicts with neighbouring countries without resorting to violence and withdrawing Sudanese troops from Yemen.

– establishing human rights as a ‘supra-constitutional’ principle, equal opportunities for women in all spheres of public life and government, with positive discrimination policies to redress the current imbalance, and enhancing the participation of youth and disabled people in public, economic and political life.

– preparing a constitution by organizing “public discussion and grassroots conferences that enable the most significant possible popular participation for Sudanese men and women in drafting a constitution” (p12). After a popular referendum to approve the constitution: pass electoral legislation, establish electoral institutions and hold general elections

As a first step, before any of the above can happen, the coordination of the resistance committees (CRC) in the state of Khartoum affirms that the military regime must be overthrown.

The CRC Khartoum submits this charter for discussion, development and signature by the CRCs in Sudan’s other states, but also requests the discussion and signature by “professional unions, pressure groups, feminist, displaced and refugee organizations, labor and student organizations, workers unions and political and revolutionary organizations” against the coup. (p14). It forbids any of the individuals and organizations that have participated in the previous regime or the coup to sign the charter, unless they publish a letter assessing the motivations for their participation and its results.

Admittedly, I have cherry-picked a bit in the charter to extract what seem to me the clearest principles. Some passages are a bit obscure or vague. The full charter can be downloaded here. To some it may appear ‘half-cooked’, to others ‘utopian’, some may even think it does not go far enough. But the Charter for the Establishment of the People’s Authority does provide a way forward, which reflects the changing social and cultural values of the Sudanese people.

Pingback: Vers un effondrement de la démocratie au Soudan

Pingback: Sudan: Revolutionary reflections, amid a raging war – Defend Human Rights Speak Truth to Power