The five posts below are the first of a new series called ‘A Plan for the Future’ which I’m publishing on substack. Please sign up here.

1. Time to replace the state

10 March 2022

The world is going up in flames, but our states are getting ready to fight each other. It is time we humans reorganize to get rid of our states. The latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change really pulls on the alarm bell, but our governments seem not to be listening. We should be radically cutting our emissions, reorganizing the global economy and preparing for extreme climate events. Instead, Western governments are rearming, getting ready to pump even more greenhouse gases into our atmosphere, reallocating funds to armies and warfare and doing nothing to curb the growing inequalities in the global economy.

NATO, the largest military machine that ever existed on this planet, was defeated in Afghanistan after an intervention of twenty years. This repeated a lesson world history has taught us over and again: even the most determined army, with an incredible superiority in technology, resources and firepower, cannot overcome the resistance of a people. We don’t need to worry about Ukraine: the Russian army will face a defeat. Yes, they might kill many civilians in the process, and destroy much of the country’s infrastructure. But we would be stupid to let this distract us from the real emergency: human-induced climate change.

Do people, anywhere in this world, desire war? Do the Russians, the Ukrainians, the Europeans or any other people want war? NO! Do we want to live securely and peacefully on our beautiful planet? YES! War is made by our governments, by the disgusting clique that is ruling Russia, and by all the panic-stricken ‘leading’ rich world governments that are shying away from their responsibility to do something about the climate crisis. But it is not enough to get rid of our governments. We need to get rid of our states, and of the ‘economy’ they have created and which makes them rich and powerful.

We humans all form part of an organism which is called humanity. This organism lives within ecosystems formed by nature on this planet. This – LIFE – is real. Our states, the economy, money, the law and political power, by contrast, are all fictions we humans have agreed on; they are not real, but imagined. Tomorrow we could all stop believing in them and LIFE could simply go on. Our society could be re-formed on a much simpler basis. Because, despite our differences, we humans all agree on pretty much the same things: we should care for each other, for our environment, there should be justice among us, we should make beautiful things and enjoy them. We all agree that it is not good to simply kill each other or destroy the environment, and that love is a better emotion than hate. These common human values could form the basis for a new global society.

So let’s all start massively disobeying our governments. Let everybody who knows she/he is engaged in an activity that is bad for our human and natural environment stop doing it at once. Let’s stop paying taxes, disobey all rules which we don’t agree with. Let’s stop believing in the Law, and strive instead for justice. Let’s stop contributing to a ruinous economy and share the results of our labour instead. Our governments can’t put everybody in jail or kill us or otherwise punish us; they can only do that when dissenters form a small minority. Besides, the police and army is populated by human beings too, and they might side with humanity instead of with governments.

Each human being is unique, and has a unique role to play within society. Each human being therefore needs to find what that role is. This means that we must start by working on ourselves. We must govern our passions, not be led by our dark instincts, allow ourselves to be checked by our loved ones; each human being needs to grow, spiritually, in mental capacities, in physical well-being and soulful happiness.

We humans have gotten so far, dominating all other life forms on this earth, because we are social animals. So while we keep working on ourselves, we must do this within communities. Each of us is part of many communities. The first and primordial community is the one we live in: our neighbours. Therefore, we should all go towards our neighbours, in our villages, apartment blocks, streets. We should get together and start organizing ourselves, sharing our resources, capacities and desires. Then we should appoint our representatives, never giving them more than an imperative mandate, meaning they represent us only in one task, only as long as the majority of the community agrees. But instead of breaking into groups and sub-groups, we should seek consensus among ourselves, even if that means talking and negotiating much longer. Our representatives can then meet other community representatives and decide on issues that concern our community but surpass it. This system of representation – a true democracy – can extend to the entire human community.

This would be radically different from the current global power structure, which sits as a pyramid above society, and whose members often have obtained their position by a combination of capacity, personal networks and ruthlessness. We should imagine this decision-making structure which extends from the local to the global level as an inverted pyramid, supporting human beings rather than dominating them. Its members do not ‘hold office’ – they are there exclusively because the communities above them, who selected them, trust them with their mandate. Their power, in other words, resides only in their capacity, not in their position.

An important point of this future world is economic equality. An hour of work by a human being should be valued the same all over the world, and regardless of the job done. A person picking up trash in nature and the one recycling it should get one credit per hour of work, just like the very ‘lowest’ representative of the human community who decides on global resource allocation, or an artist, a teacher or a cook. ‘Money’ as we know it will disappear, replaced by credit. Whether a job is worthy of credit at all is decided by the concerned community (or its representatives). If a person does her/his job well, people can allocate extra credit (social credit) as a token of appreciation, and they can remove previously given social credit when the job is performed poorly. This way, each person in the world can find his/her unique place in human society and try to excel at it. Work is not done for money, but for the pleasure of being useful to others.

I suggest we turn our backs on money now and develop a new means of exchange to replace the pieces of paper, coins or bits which constitute ‘money’ today. Money is just a social fiction, we can replace it without any pain. The trillions of dollars, euros or other currencies people have now will just return to what it really is, thin air. Let people who want to continue to believe in it do as they like, we no longer need to participate.

Property has been one of the main drivers of inequality, war and crime in our world. We must envision it differently. First, we must acknowledge that the earth and its resources cannot be individual property; they also don’t belong to the human species; they belong to themselves, or to ‘nature’. An animal, a tree and its fruit – these cannot belong to people. However, people who use them responsibly, in the eyes of their community, may continue to use them. Cereals produced on a farm are the result of a collaboration between the nature and the farmers, and the same is true of stones extracted from a quarry or fish taken out of the seas to feed humans or their industry. Thus, we can replace the notion of property of land and natural resources by the notion of ‘usufruit’, the right to use, responsibly, the products of nature and their fruits. Again, who determines whether this right exists and how far it stretches is the community. In the case of resources which can be depleted, the whole human community is concerned.

Another kind of property consists of the things made by people and traded; first and foremost their residence, and all other smaller things they use. There, the rule is that whatever one makes oneself is one’s property (and when made collectively, collective property) and one place of residence, as well as all the things used in daily life, can remain one’s property. All the rest (secondary homes, vehicles etc) reverts to the community in which they are located. Sharing one’s resources with the community is viewed positively, not sharing is viewed negatively. I have not made this up, this has been a trait of all human communities in all times. Nobody needs to own more than they can use. After one’s death, the children or other designated inheritors can receive the possessions, but they can only keep those that they use. Others revert to the community. The community is not ‘owner’ of these possessions, but their guardian.

The community thus becomes the essential building block of the new politics. All human beings together form one community; within that one global community, each individual is part of many different communities. The essential one is the geographic community, dependent on the place of residence. Other communities are formed along the lines of family, friendships, affinities, shared experiences, interests, professional activities, knowledge etc. A human being can be member of many such communities voluntarily; some are closed (e.g. families), some open (e.g. admirers of a certain artist) and some restricted by its members (e.g. professional associations). Only a geographic community may be compulsorily, if its members so decide.

The community decides on all matters of collective interest to its members; if that membership is too wide to allow for personal contact between all its members (more than 144) it proceeds to elect representatives. These representatives have a specific mandate and are recallable at all times by the community, who may then replace them with others or modify their mandate. To function well, the following principles have been observed in practice:

- A community is only as good as its individual members are. Therefore, each community member must ceaselessly work on improving him/herself, seeking self-governance of the passions, improving one’s knowledge and capacities and attaining wisdom in judgment.

- Successful communities spend a lot of time talking together, and reach decisions by consensus rather than majority vote. The formation of blocs within communities is deadly to that community’s cohesion. Although it may seem inefficient, it is advisable to continue speaking about an issue together until a consensus has been reached.

- When deciding on representatives for a specific, crucial mandate, a community may decide to appoint two people, for example a man and a woman, instead of just one. Double representation may curb the power-seeking tendencies which seem to always lurk when a person is given a mandate by his/her community and serve to redress historic inequalities within communities.

- The more time a community spends seeking consensus on issues important to it, the stronger it becomes, also when representing itself at lower levels of representation.

Oh brother and sisters, we must avert the catastrophe which is looming before us. For more than fifty years our scientists have been warning us that we are headed towards an environmental disaster, but we have done exactly the contrary from what we should do. Half of the greenhouse gases which are making our planet warmer have been pumped into the air over the past two decades. Our governments keep pretending they are going to do something about it, but have not. Why? Can we still believe that if we elect other representatives, that they will finally do something about it? For many people, it is the only hope. But we should stop fooling ourselves and be ready to start anew. The first step is to become better human beings, each of us individually, and the second step is to go towards our neighbours, meet them, and start talking.

How can we avoid creating the same kind of power structures that, in an effort to stay in power, steer humanity towards disaster? By not allowing any of these structures to exist, and above all by stopping to believe in them.

Self-governance is the key to the future; individual and community-based. We must realize that any group identity, except that of the human species altogether, is a fiction. Nations, countries and states are a fiction; companies and institutions are a fiction; even communities are a fiction. These fictions have been given a legal identity by treating them as ‘legal persons’. There are two of these fictional group identities that most urgently need to be dispelled: companies and states.

All people working in a company, and desiring to continue to work in it, must take it over and create a community along the lines mentioned above: without hierarchy. Schools, public transport organizations, factories, infrastructure maintenance institutions: these can all be managed more efficiently by the people working in them. Together with the users of their products and services, they form a larger community. For example, schools will be taken over by the teachers and staff working in them, but they need to work together with the community of parents to decide on how to advance and provide the best possible education to the children. Schools can then appoint their own representatives to discuss a regional organization of schools, in the knowledge that a common curriculum is more useful to establish equivalences of education. Parents may likewise select their own representatives to discuss the formation of a regional curriculum with the representatives of schools.

But none of these ‘lower’ levels of organization, down to a global education board, can exert power over the higher levels. The highest level remains the individual school, or class, and above that the individual parents and pupils. Collective organization and decision-making must be seen as an infrastructure, not superstructure. The mechanisms inherent to human socialization apply, of course; thus the school that steers a different course from all schools around it may face ostracism

2. A radically new economy

15 March 2022

Oh brothers and sisters, the main driver of our course towards disaster is something called ‘the economy’. This is a recent human social construct, barely more than two hundred years old (before that, there was no ‘economy’ or anything similar) and it was only adopted by many peoples of the earth over the past decades. Nevertheless it has rapidly become a fundamental assumption of our social reality and maybe the main constraint in our daily lives.

The economy is a system of distribution of wealth according to inputs (labour, capital and resources) that has grown at the same rate as human use of fossil fuels. It is controlled by powerful Western states – notably the USA and the members of the European Union – and their banks and richest corporations and institutions. The economy mostly benefits these ‘controllers’ and the networks of people associated with them, which includes almost all the centres of power in the world, including mass media and universities – where opinion is formed – and elites in non-Western core countries. It presents itself as a ‘science’ but, as anybody who has studied economy knows, it is really not a science but a set of prescriptions and theories which are notoriously incapable of predicting what will happen to the economy, even in the short term. The economy, like the state and the Law, is a social fiction, which only works because we believe in it.

Like the state and the law, the economy has undoubtedly been useful to a degree, but now it has outlived its usefulness, and it has become dangerous to our survival. Put very simply, the challenge of the economy for those who control it is to consolidate and increase their own power and wealth, while distributing enough wealth to the rest of the population to keep them from revolting. This can only be achieved by constant growth. That growth, from the late 19th century to today, has been made possible by fossil fuels. This explains why the global economy has, until now, been incapable of addressing climate change. Renewable energies cannot replace fossil fuels quickly enough; this explains why even one of the greenest countries in the world, Germany, is still expanding its coal production today.

There are many attempts to ‘reform’ the economy, mostly with two goals in mind: to distribute wealth in a fairer way, and to avert the climate catastrophe. These are both important goals, but so far these reform attempts have failed, because those who control the economy do not want to see their power base eroded. For example, in Europe the slow transition towards cleaner energy sources and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions has only been possible because new markets were created, new ways to distribute public money among the existing corporations and institutions. On the other hand, the gap between rich and poor is widening rapidly, leading to a few trillionaires on one side, and the impoverishment of billions of fellow humans on the other. There is nothing fair or logical about this widening gap: the poor are not becoming lazier and the rich are not working harder and becoming smarter. The necessary reform of the economy is an urgent but impossible task. Therefore, I suggest we must entirely replace the current ‘economy’.

Replacing the economy means a giant reset of the distribution of wealth in the world. If we decide together, at more or less the same time, to ignore all currencies, replace them with a single new currency, and redefine the rules of property, then the riches accumulated by some people at the expense of all others will simply vanish. Money and property laws are only worth something because we have collectively agreed to give them value. If we make new rules and abide by those, the transition could be seamless, although we can expect the current power-holders to use violence to maintain their privileges. But this violence will only be effective if the numbers of dissenters are small; an entire population cannot be put into prison or massacred.

A violent transition may put off many people who are ready to help our world survive this crisis. But the alternative (letting the ‘economy’ emit more greenhouse gases and not prepare for the pending catastrophe) is much worse. In any case, we should never resort to violence, except perhaps in self-defense, because those who control the economy also have a monopoly over the use of violence. Hopefully, many of those in power will support the great shift, if they value human life and the planet more than their own wealth and comfort.

What would such a new economy look like? Here are some guiding ideas. First, we should distinguish two sources of wealth: that produced by nature, and that produced by human effort. The resources of nature, in turn, are either renewable in a human life-span (for example food, rainwater, animals) or not (for example minerals, top soils, glaciers or a species of animal). Renewable natural resources can be managed by the communities involved in their use and are basically free. The non-renewable resources must be centrally managed by the entire humanity, with two principal considerations: the impact of their use, and the responsibility of current to future generations. Based on these two criteria, non-renewable resources have a price. Logically, this price should be very high to ensure that future generations – for tens of thousands of years – also have access to them.

As to human labour, in principle one hour of effort must have the same value all over the world, but to this base value (1 credit per hour of work) social credit can be added; thus one hour of work by an expert or an artist, or necessary work that nobody else wants to do, will be socially more valued than an hour of routine, uninspired labour.

On this double basis, a system of value for each object and service can be determined. Let’s explore some examples:

1) somebody gives you a haircut in half an hour. You pay this person half a credit. If you are happy with the barber’s effort, you can tip with some social credit. If you appreciate that the barber has invested in better scissors, chairs and a nice salon, you can add more social credit. But the base amount the barber gets can not be more, nor less than half a credit if she/he worked for half an hour. A barber, or anybody else in the world, cannot charge two credits for an hour of work.

2) you buy a wooden chair. The wood is a renewable resource, but it had to be cut, transported, properly dried, prepared for furniture making; then the chair had to be made, materials such as varnish or paint applied; and the ready chair had to be transported to where you buy it. For these labour efforts and material inputs a standard price can be calculated, consulting not only experts but all people involved in this production chain, to ensure this price is fair. Say six hours of work by four different people (the lumberjack 15 min, the wood-preparer 30 min, the carpenter 5 hours and the shopkeeper 15 min) went into making the chair, while the varnish/paint and primers cost .5 credit (in fabrication time costs) and the transportation to the town where you buy it another .5 credit (in time of all the people involved in maintaining this transportation line); then the base price of the chair, in your location, will be 7 credit. Note that you do not pay for the wood. Why would you? It belongs to nature and it will never be yours. If you appreciate the craftmanship of the carpenter, or the quality of the prepared wood, or the service provided by the shopkeeper, you can pay them with extra social credit.

3) you buy a plastic chair. This plastic chair can be made from 100% recycled plastic, and the energy used to melt, remold and transport it can be 100% renewable; this means that the labour cost for your plastic chair is insignificant. Forty people working in the plastic recycling plant, say, produce 10 tonnes of plastic items in twenty working hours (altogether 800 manhours) and say your chair represents only 0.002 % of that, or 0.016 credit in labour costs. But to this other costs are added. First of all, the plastic had to be collected, and the hours of labour involved in this must be included in the base price of the plastic (unlike that of the wood). More importantly, the world council on plastics may have decided that no new plastics will be made, and that half of the existing stock of plastic waste in the world must be reserved for future generations, as plastic loses properties with each recycling cycle. There is thus a condition of scarcity based on the fact that oil, the original source of plastic is non-renewable (in a human life-span). The world council on plastics may decide on a kilo price of two credits, with which the following activities can be paid: dealing with the health hazards for the workers of the recycling plant and the surrounding communities; subsidies for the machinery required for the plant, to encourage the use of sustainable and clean machinery; and reforestation activities to offset the climate change effect produced by the original appearance of the plastic. Thus a kilo of recycled plastic may cost two credits. If you bring your own plastic items to recycle, this price will decrease.

4) You buy a new battery to replace the failing battery in a child’s toy. But you are not interested in ‘having’ the battery, only in using it. So you contract the electricity providers which deliver power to your home, to seek an agreement on an energy solution for this toy. The electricity providers are then motivated to find the most sustainable and energy-efficient solution, so that you pay less while they earn the same. They will not earn more, because an hour of work is the same price everywhere. But the electricity providers can seek to obtain social credit by providing a sustainable, low emissions solution for your electricity provision, including your child’s battery-operated toy, and by providing a good service. Also, when the toy stops working or you decide to dispose of it, the battery reverts to the energy provider.

Characteristics of the New Economy

The new economy is geared towards avoiding waste and achieving maximum sustainability, especially in terms of energy use. It is a real economy, allowing the human species to deal with the resources provided by its environment in the same way that a poor household does: intelligently, wasting as little as possible. It recognizes that what the Earth and nature produce does not belong to any person, nor even to the human species, although the human species is called upon as a steward to guard the production of nature, given its position at the top of the food chain. Thus the human species, now acting as an organism, decides on the best allocation of the available resources in the interest, also, of other species and future generations.

This requires intelligence and wisdom, which are two features that the human species must develop both individually and collectively. The instincts to property and territory – the child who grabs something and says ‘mine’ and starts crying when a stranger enters his/her territory – will not disappear, but each individual, and each community, must learn to overcome them insofar they are damaging for others. A community which happens to live on top of a precious resource (say, lithium or a very rare species of medicinal plant) can lay no claim to this resource, although they would have to be fairly compensated for the extraction of this resource in case it disrupts their lives. In the case of a rare medicinal plant, as long as the community does not threaten the species by over-exploitation, for example, it can use this renewable resource; but it cannot object to people from elsewhere coming to study the plant and attempt to plant it in other places. Or to an outside intervention should they threaten the survival of this species of plant.

By separating credit from social credit, the instinct to hoard resources can be checked, and the prime mover of human conduct – the desire to be appreciated by others – can be given free reign. Credit is generated by human labour, and by assigning value to non-renewable resources. It circulates in fixed amounts. The credit one pays for a service or product is transferred for once and for all to the people who have provided the effort for it. This can be a very large and complex group of people, and it will require skill to properly assign value. But only labour and the use of non-renewable resources are paid for in this way. Assuming an economy where non-renewable resources are barely used because they are so expensive, it is mostly labour (or effort) which is paid for by credit. Credit ensures that everybody who does some work deemed useful by the community, or by clients/customers, receives adequate compensation for it. Nobody should need to go hungry.

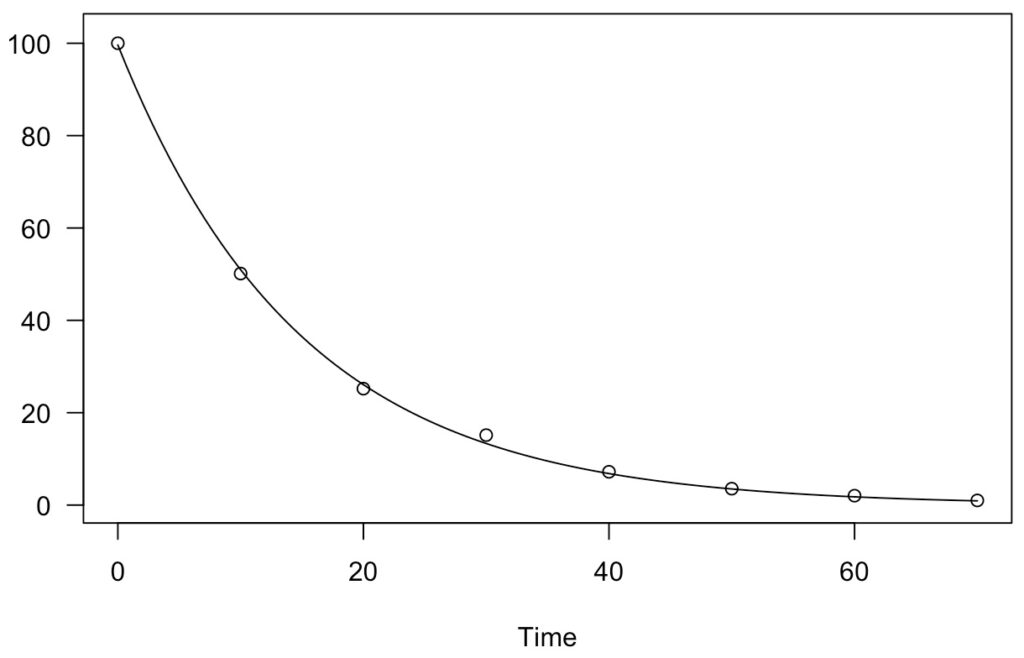

Social credit, in contrast, works differently. Once given, it can be partially retrieved, according to an aymptotic curve as shown below. For example, you may have given social credit to the waiter and kitchen of a restaurant while paying the bill, but that same evening you fall sick and you decide to retrieve the social credit you gave to the kitchen (letting the waiter keep his/her share). But you can only retrieve 90% at that time; a day later it may only be 85%, and a week later only 70%. In another example, you may have given social credit to a representative of your community whom you think is doing very good work. But later you find out she/he has been abusing that position for her/his personal benefit. With the other members of the community you decide to recall and fire that representative, and every person retrieves the portion of social credit given that has not been made permanent (see curve below).

This means that social credit that you receive is not all yours, but only gradually becomes yours, while a part of it can always be reclaimed; this can lead to ‘social bankruptcy’ if mismanaged.

A more humane ‘economy’

Today people seek to accumulate riches for two reasons: to provide security for themselves and their loved ones (in some societies the latter may form extended communities); and to gain social recognition. In the proposed model, security is provided by credit, and recognition by social credit. Credit is non-inflationary (an hour of work/effort will always be one credit) while social credit may experience inflation or deflation. It may be smart to encourage positive social interactions by allowing an increase in overall social credit, of say 5%, which is spread equally over the giver, the recipient and the communities both belong to. Vice-versa, negative social interaction (when credit is withdrawn) can cause an overall decrease in social credit, withdrawn from the concerned parties. Social credit can only be given to recipients outside one’s community, for specific actions. Thus, family members, friends and members of the same community cannot give each other social credit.

To work, this system needs near perfect information: this is provided by a host of implicated experts and users who calculate the value of products and services, and regularly (for example yearly) recalibrate these values, based on collected data. This system also needs total transparency, meaning that each individual person’s credit and social credit ratings, and what he/she has done with them over the course of her/his life, are there for all to see.

Credit is person-bound. When a person dies, her/his social credit evaporates (all the social credit received or given may, of course, be registered for posteriority). Basic credit can be inherited by a person’s heirs, or third parties as decided by that person in a testament, but the amounts will never be very high, as they depend on how much that person has worked (and not spent), which is a finite amount.

Property – now limited to man-made objects – is freely transferable. A person may decide to give an object, even a house (which usually will be the biggest object anybody has) to any other person. But a community may intervene to reallocate property. For example, if a person inherits a house in a village or an apartment in a town, but is rarely present, the community may decide to reallocate that house to another family. Or if a person has collected a large amount of items – say many ancient artifacts of a community – the community may decide to intervene in the succession to ensure that those artifacts remain in the community, instead of being taken away by a heir. If a person owns two motor vehicles in a community which needs these vehicles, but will not lend them when needed, the community may expropriate them. Such cases, when litigious, will be adjudicated by judges (see later). The rule for property is: as long as it is being correctly used (or not required for the functioning of the community) it may remain in private hands.

One of the worst aspects of the current economy is that it is occupying ever greater spaces of most people’s lives, making people run incessantly, encouraging them to work harder and harder. Most of this work and running around is not useful, either to the individuals doing it, or to the community, or to the planet. We consume a lot of energy and emit greenhouse gases to play our part in an economy which is both increasingly unfair in its distribution of wealth and opportunities, and deeply wasteful. Many people are unhappy with the work they do, realizing much of it is pointless. But it demands so much of our time that we can no longer take care of our parents, our children, our loved ones and our environment. The ’economy’ makes us believe it is more ‘efficient’ – or sometimes compels us – to delegate those tasks to other people, whom we pay for that work. For example, we pay taxes so the government can run nurseries and subsidize old people’s homes. Besides being highly wasteful, this ‘economy’ is dehumanizing and commodifying our social relations. The new economy will result in people working much less, as there will be no compulsion to contribute to the huge current wastefulness and meaningless work. We will have much more time for our loved ones, the environment and creative pursuits. We will have more time to think, interact and develop ourselves.

3. A vision for the future of humanity

17 March 2022

Oh sisters and brothers, we humans have lost our sense of direction. Some of us are religious or otherwise spiritual and can give sense to their lives, but many of us are lost. We are living in extraordinary times. Our planet’s chemical processes are fluctuating rapidly, the 300 million-year history of life on earth is undergoing a mass extinction, our 2 million-year old existence as a species is in danger, our human history of a few thousand years has precipitated the environmental crisis and led to the greatest injustice among peoples on earth, and this is all happening within our personal life spans.

I believe we can only survive if we all together switch to a new form of collective organization; one that takes into account that humanity forms one species, like a macro-organism living among other macro-organisms on our planet. Below the level of the species, the first unit is the individual human body, and below the human body, the first unit is the cell. Above the human species, the first unit is the earth itself, and above that the solar system, the galaxy etc. Between the human species and the individual human being there is no natural unit. Races, nations, tribes, religions, professions, neighbourhoods, even families: all have questionable borders. Therefore, each individual human being should take as a reference for action the entire humanity (keeping in mind that humanity is but one macro-organism among others).

We must wake up to this planetary consciousness, to our consciousness of being together, humans, one organism. An organism which needs to be discovered, which is in permanent evolution, adapting itself to the conditions of life on this planet. This should be our goal, as humans: to develop humanity, to become an intelligent organism which nurtures life on earth, and which may have a cosmic destiny. We humans have always had intuitions of a God, or of gods, of the endless energy and plasticity of this reality we live in, of invisible laws which we can not yet understand, and of our individual capacity to reproduce the cosmos within us. All cultures on earth have brought forth these notions in their legends and artistic imagination; to some they appear as memories, to others as dreams.

We have imperfectly understood the vast potentials of life itself, and of our human capacity. We are just starting to understand reality around us. Our scientific knowledge is still at the beginning of what could become a long trajectory of discovery. Our collective mission should be to develop this.

If humanity is measured along the scale of a human life, we may be in the adolescent phase now. The beautiful and innocent childhood when our parents were gods lies behind us; many of us have even stopped believing in them. Our world politics are of the level of a school courtyard: we are divided into groups that are often in conflict with each other, with some bullies and a network of elder children who maintain the leadership and set the rules for the rest. Like adolescents we are unaware of ourselves and careless with our environment. We must grow up. Become responsible adults, take care of our environment and of each other, cease the useless conflicts.

It is impossible to say where this will lead us, as nothing like a conscious humanity has existed before. We can imagine things, but we can’t know what the society of the future will look like. There is no blueprint for the coming society. It must grow organically. It starts with the individual human being, who should honour life and seek to develop his/her own destiny, conscious that each human being is unique. Below that are all levels of collective self-organization, through which a highly complex organism can self-organize, grow and evolve, constantly exchanging information and producing life. This organism lives in harmony with the rest of nature.

If we conceive of ourselves as member of such an organism, my friends, and agree on a few simple rules that govern our collective life – only ten rules, not more – and we set up new mechanisms of exchange among us, based on this amazing and world-changing invention of the internet which connects us all; if we do that then we can switch from this life-threatening current social, economic and political system to one which nurtures life. We may not yet be intelligent or wise enough to truly live in harmony with each other and with nature, with this earth we live upon, but we should start striving to now.

Not tomorrow, we must make the switch now: individually and collectively. We must do it for ourselves, for the future generations and for all life forms that we threaten today.

4. The Case for Self-Governance

20 March 2022

My friends, you may believe I’m calling for radical change from the safety of my privileged European middle-class background. Indeed, I plead for a collective wake-up moment, whereby we agree to stop supporting the state (by not paying taxes and not obeying its laws) and instead turn to self-governance in harmony with nature and based upon our own laws. I also call for the immediate cancellation of the ‘economy’ and a redistribution of property upon a new basis, not allowing human property of anything produced by nature. What’s more, I argue that if we don’t move fast, humanity will face imminent disaster. You may consider that my ideas are naïve and go against common sense, and that they may even be dangerous and could lead to disaster if ever applied. Let me develop some arguments to clarify my position and examine this notion of ‘common sense’, and what may happen if we let it guide us.

My confidence in self-governance comes from years living and working among people who live without a functioning state; I encountered this, for example, in Afghanistan, Somalia, Kurdistan, Tajikistan and Yemen, and I studied self-governance among the Zapatistas in southern Mexico and read about it among, for example, North American Indians. I have seen that stateless people manage their collective affairs quite efficiently; each individual member of society often plays a part which is largely self-designated but there can be intense concertation to achieve collectively desirable outcomes such as peace and security, education, access to the outside world, energy generation or cultural self-expression. In Rojava (Northeastern Syria) I witnessed, moreover, that a system of self-governance can deal with large populations and the associated complexities; it is not circumscribed, as its detractors frequently allege, to small communities where people can have face-to-face contact.

This has given me confidence in self-governance. I have further understood that even in highly ‘developed’ Western societies, most people self-govern most of the time. We do not treat people well out of self-interest or for fear of sanction, but simply because we aspire to be liked, to be found sympathetic. Rutger Bregman, in his book ‘Humankind’ argues that it is not the ‘survival of the fittest’ but the ‘survival of the kindest’ which characterizes humanity’s evolution. Women, in the past as now, when thinking about a male to be a husband and a father, prefer a sympathetic and reliable to a strong but brutish man.

What is common sense?

Our ‘common sense’ nevertheless tells us that ‘the survival of the fittest’ and the ‘law of the jungle’ entail that human beings need a state to constrain them, to impose its laws on them and make them behave, and to guarantee equal rights to all citizens. Common sense is squarely in favour of the state and the market economy, and thus forms the greatest obstacle to radical change. But we should ask two questions: 1/is common sense usually right? and 2/where does common sense come from?

The first question appears a bit nonsensical, because what is right or wrong is determined by human beings, and precisely falls within the domain of common sense. For example, it is common sense that it is right for every person to have their own motor vehicle, as it is common sense that people will not want to share the use of their possessions (such as cars) with others. In terms of morality, common sense seems to be ‘right’ by definition. But in an objective manner, we may see that common sense can be wrong or counter-productive. As examples we can mention the common sense which has guided liberal capitalism since its origins: that nature can be plundered freely by man, and that this plundering has no important consequence for life on earth. Until the end of World War II it was common sense in the West that some human races are more advanced and powerful than others, and that the strong races are destined to dominate the weak ones. A tenet of common sense today which we need to discard is that economies must grow to remain healthy.

These examples indicate, too, that what is common sense changes over time. Think of how dominant Western white males think about the role of women in society over the past century. The latter example also points out how exclusive, even totalitarian common sense is. People in Western societies find it hard to believe that people in Muslim societies do not give equal rights to women, in other words that common sense among Muslim societies is comparable to the common sense in the West during many centuries. Why would that be so hard to understand? How and why does does common sense change, who is behind these changes and what are their effect?

Let me use the word ‘consensus’ instead, because common sense sounds passive and the word doesn’t suggest change. The consensus over for example how our society and economy should work is established by what Antonio Gramsci called ‘organic intellectuals’. This means intellectuals who are embedded in the structures giving meaning to the world, and who contribute to their development. For example, university professors or media experts. These characters and a host of other, related ones (such as the people writing schoolbooks or choosing which books are bought for libraries, or which artists are celebrated by exhibitions) are continuously reinforcing and adapting the consensus. As a group, these people can be referred to as ‘the elites’, which etymologically means ‘the choosers’. The consensus continuously adapts to new power players emerging in society – such as the LGTBQ movement in core Western countries – and to contextual factors – such as global warming. At the same time, the consensus maintains and reinforces the position of the existing players, for example the fossil fuel giants and the hegemonic ‘great powers’.

The consensus that underpins global societies thus first takes into account the objectives and interests of the ruling elites, in their ever-changing composition. The surrounding social layers believe that their best interest is to stay close to and incur the favour of these most powerful players, who control, for example, global money supplies. These subordinate layers then formulate the consensus which is spread through society. A recent item of consensus is that global warming is the responsibility of individual consumers, and that each person must reduce her/his demand of fossil fuel energies to let the markets operate their magic. This lets the fossil fuel giants, some of which have made their biggest earnings ever in 2021, off the hook; it also allows states to continue to provide trillions of dollars of yearly subsidies to the fossil fuel industry, because it places such issues outside the purview of the consensus, which proclaims that one should focus instead on one’s individual consumer behaviour, recycling household waste and buying an electric car to replace the still well-functioning petrol or diesel car.

Consensus and common sense thus have little to do with ‘truth’ or even what humanity needs right now; they are an expression of ruling elite interests and values. Consensus seems to be the active part of this (the word implies a group of people seeking consensus) while common sense is the passive aspect, the one presenting itself as an unquestionable given. One can argue against a consensus, but not against ‘common sense’. This is why ‘common sense’ must be overcome. In their recent book ‘Consequences of Capitalism’, Noam Chomsky and Marv Waterstone argue this point powerfully.

The predictable future

Let’s return briefly to the state and the market economy, which common sense both sees as unassailable natural realities of our collective life. Both concepts are not much older than 200-250 years, as David Graeber and David Wengrow point out in ‘The Dawn of Everything – A New History of Humanity’. This means that for all the thousands of years of recorded history before that, human beings lived without them. Now, however, common sense tells us that living without them is impossible. This is clearly a politically-produced impression, which serves the current powers. If we do not dispel this illusion, we will remain unable to act, waiting for our rulers to act in our stead. But why should they demolish their own base of power? They will seek a solution that seems good for them, and which perpetuates or increases their power; the impact on humanity is much less important.

We can imagine what happens if all the world’s populations stay quiet and hope for their rulers to come up with a solution. Global and domestic inequalities will continue to increase, resulting in an economy where a few rich people dominate global wealth, while the masses are increasingly desperate to get jobs. Thanks to current economic policies, we already face a situation where the richest 1% of the world population controls 45.8% of the world’s wealth, while the poorest 55% own 1.3% of global wealth. The rich will convince the citizens of their countries, through the organic intellectuals, mass media and mass education, that this inequality is natural and that their enemies are poor people in other countries who seek to gain a livelihood. The rich and powerful have already been fanning the flames of nationalist or ethnic sentiment to deflect the blame from themselves; Trump’s presidency was an example of this novel kind of ‘populism’.

The consensus in Europe today is shifting from a belief in the benefits of the social welfare state to one where trillionnaires like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos are idolized, while all society’s ills are blamed on the weakest people, for example migrants and people who can’t find jobs. It is extraordinary how easy it appears to be for ruling elites to ‘manufacture consent’ and redefine common sense.

Populations of developing countries in the tropical zone, hard hit by climate change, may attempt to migrate to areas where they can survive. Many of these areas are in the Northern hemisphere, but here they will face populations, their governments and their armies determined to stop them. Given that almost all stockpiled weapons are in the North, one can easily imagine a bloodbath among migrants, or (if Southern populations don’t try to force their way North) a humanitarian catastrophe. Either way, we may expect a considerable percentage of the world population to die, almost all of them from developing countries.

This scenario is considered the most likely by military realists, and NATO armies have increased their spending to prepare for the coming ‘climate wars’. Refugee flows are only one aspect of this; other aspects are resource wars (where countries fight for the control of valuable water sources, still arable lands and the control of precious materials such as lithium and uranium or the remaining oil deposits). Since these latter conflicts may well pit the armies of the strongest nations against each other, and there are still enormous amounts of nuclear weapons, a total catastrophe is not unthinkable. The conflict between Russia, Ukraine and the West serves to remind us that war is not such a distant prospect.

In the first scenario (global warming increases global inequality and migrants are rejected by Northern populations) we will see a breakdown of law and order, and of the state, in most developing countries. This is already taking place now. Many of the regimes supported by the West in Africa, the Middle East, Latin America and parts of Asia exercise control only over part of their country; other parts are governed by political Islamists or regional forces. In the second scenario (fighting for resources between Western states degenerates) this breakdown will extend to the Northern countries (and those belonging to ‘the West’ like Australia and New Zealand).

Self-governance now!

Wherever there’s a breakdown of law, social order and the state, people revert to self-governance; this can be observed in many parts of the world. It is rarely contested or contrived, but usually a natural fallback option. This happens also in moments of crisis. For example, Bregman examines the stories of plane crashes to see what happens when a group of strangers suddenly finds itself in an extreme situation which requires them to cooperate in order to survive. It appears that most frequently, perfect strangers help each other. They rarely put their own survival or interests first. Such self-serving behaviour (accepted by economists as the norm and the basis for all modelizations of human conduct) is seen as pathologocial by respondents. On the other hand, it is considered ‘normal’ behaviour by people involved in plane crashes to first help others (the weak, notably). Economists don’t take into account ethical behaviour because they cannot modelize it, but that doesn’t mean it is not a driver of human relations.

We can therefore expect a return to self-governance anyhow, when the power structures of the world (or part of them) collapse. I propose to switch to self-governance before it’s too late, and to save many of the aspects of the current world which we appreciate – for example, a free and easily accessible internet. Let’s not wait and watch as our governments first remain in denial over the crisis, their role in it and their ability to do something about it (besides making grand statements); let’s not be carried along, when the environmental catastrophe hits us full in the face, by our government’s efforts to identify scapegoats and have us attack them; let us not witness our ruling elites retreat to their underground luxury bunkers with swimming pools and endless supplies of food and ammunition when they conclude they can do nothing to save the world and admit that the system has collapsed. Let us act pre-emptively instead.

We should no longer believe that it is ‘common sense’ that self-governance is either not possible or leads to dismal outcomes, that inequality is natural and that the rich should be admired, not blamed. Instead, we should remind ourselves that self-governance has been the norm for human collective existence for nearly our entire history as a species. We could realize that the internet and a growing planetary conscience among all peoples – that we are fundamentally equal and stand together before the challenge of survival – have added vast new possibilities to self-governance. My sisters and brothers, let us wake up and try out this new way of being together. Leave your houses and your social bubbles, go meet your neighbours and start talking!

5. Solstice Pause: 20-22 June 2022

24 March 2022

Dear friends, just imagine we all took a pause. I mean, all the people on the world. We stop running around for a few days; we all stop working. For a few days we slow down, we relax, we look around us and reconnect with the people, nature and the things around us. We breathe, we live.

Something similar happened to many of us living in cities during the first Covid-19 lockdown, between end March and June 2020. Suddenly, almost all cars stopped driving, the planes stopped flying, there were less people in the streets because most reasons for going out had disappeared; wandering too far from home without reason was even made illegal in many places. The worst aspect of that lockdown was that we could not meet people (or we had to do so secretly); that was especially hard on those living alone. But most people I spoke to enjoyed the sudden pause in our frenetic lifestyles, and (for those living with families) the time spent together. The improvement in air quality was noticeable after a few weeks. Many of us also experienced the revival of nature: animals coming back into the cities, beautiful weather, clean trees. It was as if nature was instantly grateful that we stopped making so much noise, gas and fuss.

Many of us had expected that if all ‘work’ activity suddenly ground to a standstill, the economy would collapse and our society with it. But not at all. Food was still growing. The relatively small amount of work required to harvest, process and transport it to our shops was easily accomplished. Our dwellings, our energy, water and communications systems were not affected. It turned out, suddenly, that it is perfectly possible to live at a much slower pace than usual.

Just imagine that on one day we collectively stop pumping oil out of the ground. We turn off the mining machines, anchor the ships, close the taps on the pipelines. We switch off the saw mills and most of the agricultural machinery. All factories stop working, nobody turns up for work. All the offices remain empty, as do the stock exchanges and the TV stations. All transactions cease. We stop going to school and through our daily routines. Instead we relax, go for walks, spend time with family and friends, take care of our gardens and things. We breathe, enjoy: live! We try not to turn on our machines. I’m sure that after a few days, the air will already be cleaner. Nature will thank us; or rather, the part of nature that is in us will feel gratitude.

We can decide to do that for a few days, and then resume all our normal activities. We can then reflect on the experiment; then maybe try it again, for a bit longer. I believe our economy will not come crashing down. It will stop capital accumulation for a few days, but nobody will die.

A pause will also allow us to reflect on our economic system. What needs to be done, what doesn’t. Most of us, brothers and sisters, are doing useless work. We do it for the money or to comply with social pressure around us. But we know it is not useful for our fellow human beings, and not good for the earth. It that is the case, we should pause it; it is better to do nothing than to do work which harms the earth or contributes nothing to social well-being.

How would such a pause work out? Let’s start by imagining somebody who feels compelled to work hard every day, and who might object to pausing.

Let’s say you’re a rickshaw driver. You help people get around town. If there’s a sudden pause, there will be a big drop in customers, and thus of income. You must pay the rent on your rickshaw, on your home, and you would prefer to work every day. You may think this pause is not good for you. But it is. You will sit at home or hang out with fellow rickshaw drivers who have no work. If there’s a customer, you can start your engine and provide that useful service for him. There’s no police to tell you whether you may or may not work. As you wait for the days to go by, you breathe better, you have time to talk with your colleagues; you may come up with a good plan together. You can relax, take care of your family or your residence if you have one. You can do things you normally don’t have the time to do, like go out of town with friends. After the agreed few days, you get back to work like everyone else.

Now imagine you’re working in an office under a boss you don’t particularly like. You know most of your work is pointless for society and for nature. You also know your boss may want to fire you if you stop working. But if everybody stops at once, (s)he can’t fire the entire staff. Anyway there’s no more work to do if all counterparts are also pausing, also not for your boss. That’s why we should pause all together.

Imagine now you work in a grocery store. Fruit, vegetables, meats, dairy and other fresh foodstuffs are still brought in from the surrounding markets, because produce is still growing on farms and we should not let it go to waste. Some trucks will still drive on the motorways and through our towns. People working in this chain will have to work fully, or find people to share the workload with them. Hospitals will also stay open, and a few other institutions; but most will close, like during the first lockdown.

Our activity and energy consumption levels will probably drop by over 90% during the pause days. It may show us that a radical shift in our socioeconomic model is possible. It may allow us to contemplate a society different from the frenetic, almost autistic one in which we now live.

It is said that each human is only six handshakes away from any other human. If that is so, we must agree on a date and then pass the message on to every person we know. If each person receiving the message passes it on to all people she/he’s connected to, the entire world can be informed in six steps.

So, what do you think? Shall we agree on a date? I suggest a pause of three days on 20, 21 and 22 June, 2022, starting on the moment the Sun passes the dateline. We can call it the Solstice Pause. We take this pause mostly for nature, but also to socialize. Who’s with me?