PhD notes

Evolution of Somaliland’s foreign relations over three decades

Not one member of the international community supported the Somali National Movement or the secession of Somaliland, and the country received practically no assistance during its first years. All the founding conferences, up to Hargeisa, were self-supported. Today, as we will see below, Somaliland receives quite a lot of assistance, also through its government. But during the first decade and a half of its existence, Somaliland seemed neglected by most countries in the world.

The refusal by the first UN mission (1992-1995) to accept Somaliland’s secession made any discussion of recognition by member states difficult. But early on Somaliland came to be accepted as a de facto state. The European Union opened an office in Hargeysa in 1994 (it has not been staffed permanently). Like the UNDP[1] it provided small-scale support to some projects and maintained a direct relation with Somaliland’s successive governments[2]. Some EU countries, notably the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway have been long-time supporters of Somaliland, but their intervention in Somaliland has been discrete and they have not lobbied for recognition in international forums[3].

NGOs gradually returned to the country but did not engage with the state-building effort. In principle they prefer to deal with local authorities in their areas of operation than with the government. Over the years the state managed to establish a measure of control over international agencies operating in Somaliland (e.g. being informed of their activities, taxing staff salaries, ensuring project equipment stays in the country). But NGOs programs are decided on in foreign capitals and alignment with government priorities was (and remains) coincidental[4]. Many NGO activities are funded through country-wide programs, wherein Somaliland is but one of the regions of Somalia. This leads to occasional conflicts, but altogether the government prefers NGOs to continue delivering services to the population, even when they do not regard Somaliland as a sovereign state.

The situation improved for Somaliland after 2007, when international interest in Somalia sharply rose[5]. By then a decade and a half had passed since Somaliland’s independence, and the country had been peaceful for a decade. It was avoiding the wave of piracy and the Islamist insurgency that raged to the East and South, and provided a much easier work environment than federal Somalia for international agencies. The EU maritime security capacity-building mission ‘EUCAP Nestor’ upgraded the central prison of Hargeisa, UNDP stepped up its police training activities, and larger aid agencies such as GiZ expanded their operations and came to work closer with authorities. This was all accomplished without furthering Somaliland’s claim of recognition, to the government’s frustration. The presence of international agencies strengthened the international perception of Somaliland as a functioning de facto state, but Somaliland’s government would have to wait until the establishment of the Somaliland Development Fund to receive direct support. That fund was established in 2012 by international donors and it was the first to directly finance projects of the government.

The donors mentioned above, long-time friends of Somaliland, agreed to support the further development of Somaliland’s state after the election of President Siilaanyo in 2010. Following international best practice, they insisted that the government should set its priorities straight, develop a long-term vision and work both out in a national development plan. The government produced a Somaliland National Vision 2030 entitled “A Stable, Democratic and Prosperous Country Where People Enjoy a High Quality of Life”[6] and a National Development Plan, both duly broken down into pillars and cross-cutting themes, and listing priorities. Although donors had reservations about the quality of both documents, which listed all desirable future developments of the country without a real strategy or prioritisation[7], they agreed to set up the Somaliland Development Fund to support the government.

If the authorities of Somaliland saw this as a first step toward recognition, they were wrong. Despite being donor-driven, they soon found out that most donors disregarded the plan, for the simple reason that they do not consider Somaliland a legitimate state[8]. The consultants noted “On the part of the Government, it will need to be commonly understood by both Government representatives and the citizens that, due to its position as an internationally unrecognised Government, there are members of the international community that cannot engage with Somaliland without a sign off from the Federal Government of Somalia”[9]. Indeed, donor plans continue to be aligned with Somalia’s national planning process. However, by creating the Somaliland Development Fund, the donors provided a way out for themselves, funding the government without recognising it.

How non-recognition helped Somaliland

Many, if not all analysts of Somaliland agree that the absence of international funding for Somaliland’s state formation process, up to and including the first cycle of elections, was essential to its success[10]. But they often assume a contradictory position. On the one hand they praise the autonomous nature of the state-formation process and its reliance on local social, cultural and economic resources. On the other they deplore that non-recognition has made state-formation more difficult, as the authorities could not access the external support typically given to state reconstruction in post-conflict situations. Such contradictions may be explained by a feeling of moral outrage at the non-recognition of Somaliland by the international community[11], but they regrettably downplay the disruptive nature of external aid, which we shall presently explore.

It may be revealing to speculate what would have happened if Somaliland had been assisted from the outset by the international community. Sarah Phillips (in “When Less Was More”, 2016) uses the case of Somaliland to question the following assumptions of Western state-building and post-conflict transition:

- An institutional endpoint must be predefined, preferably with deadlines; usually this endpoint is democratic elections after a constitution has been adopted through a national referendum

- the more inclusive the settlement, the greater its legitimacy and thus the stronger

- effective Weberian governance institutions are essential to maintain peace

- external assistance is necessary to end conflict and support the transition to peace

Philips notes how important is was that Somaliland’s negotiation processes had no predetermined outcome. The agendas for the national peace conferences were vague and changed during the negotiations. Instead of proceeding through milestones, the processes evolved organically. Voting was rarely used; consensus was preferred[12]. When seemingly intractable issues arose, parties were given deadlines to come up with a solution that would be acceptable to all. If the deadline could not be met, the chair might ‘fall ill’ thus giving parties more time to hammer out a consensus[13]. By extending deadlines for the outcomes determined in Borama in 1993 beyond what any donor would have accepted – eight years for a constitutional referendum and twelve years for the first parliamentary elections – the state secured sufficient buy-in of most sectors of the population and their ruling elites to solidly root itself in society.

On the issue of inclusiveness, it is unlikely that the mostly Isaaq elders who convened with the SNM leadership in Berbera, Burco and Sheekh would have met the criteria of international partners. UNOSOM, as we shall see below, clearly did not find them representative for Somaliland’s population. Where were the women, youth and minority clans? But as Phillips notes, a narrow interest-based coalition may initially work better in terms of providing security and stability than an early attempt to rope in many oppositional groups, contenders and excluded parties. We have seen how the reliance on less than a dozen traders, almost all of them Habar Awal, allowed Cigaal to demobilise the soldiers and reintegrate them into the national security forces and launch the national currency. We have also seen how the first governments tried to integrate new social constituencies into the governing compact at each opportunity. As Philips puts it: ” While this collusive model of development chimes with historical narratives of state formation in Europe by sociologists such as Charles Tilly and Norbert Elias, it is out of step with contemporary international expectations that peace and development emerge through inclusive, liberal processes that are conducted through the channel of formal state institutions.[14]“

With ‘effective Weberian governance institutions’ Phillips means institutions based on a legal-rational source of legitimation, or the institutions of the modern state – including a clearly (and constitutionally) defined separation of powers between the executive, judiciary and legislative, a de-politicised bureaucracy whose first loyalty lies toward the state, and an impartial administration and forces of law and order. As proponents of statebuilding hold that true and lasting peace can only emerge when such structures are strong – i.e. when the state has the monopoly of violence – the focus initially lies on building such institutions[15]. In Somaliland, however, the very weakness of formal institutions appears to have provided an incentive for peaceful cohabitation between those with the capacity to organize violence – a “finding that runs contrary to the structural accounts of order that dominate the literature[16].”

Note how statebuilding is often conflated with peacebuilding[17]. Usually peacebuilding is seen as a temporary measure, and only statebuilding can achieve lasting peace by channelling political opposition and social contestation through the institutions of the state[18]. As a result, under the guise of preventing conflict, statebuilding is advocated in ‘fragile’ countries. This leads to technocratic interventions where both peacebuilding and statebuilding are seen as a sort of risk management tool[19]. But in Somaliland, even today, statebuilding and peacebuilding evolve in different realms. Statebuilding causes conflict, which it is up to the non-state elders to solve. As we have seen, it is only in this sense that Somaliland is still a hybrid state today.

Finally, on the issue of external assistance to peacebuilding processes: we have seen in Somalia as well as in many other externally-supported post-conflict peace processes how external funding, especially when coupled with the exigency of ‘inclusiveness’, leads to the emergence of small groups (‘political shops’ they were called in Dari) that claim to represent a large constituency, hoping to gain a place at the negotiation table; or how warlords transform their military success into internationally supported political power, thus gaining legitimacy and access to funding. At a more prosaic level, invitations to luxury hotels with generous daily stipends do not incentivise political expediency among delegates. The Eldoret and Mbagathi conferences in Kenya which led to the establishment of the Transitional Federal Government lasted nearly two years and cost the international community many millions in hotel bills and stipends, although the resulting government had little legitimacy and power. De Waal notes, in the context of South Sudanese peace talks, how delegates quickly reached an accord when donors stopped footing their hotel bills.

In Somaliland, local hosts provided support to the negotiations, but this was reciprocated by ensuring that these hosts would get a deal agreeable to them. But in principle, each delegation sustained its own expenses. There was no pecuniary advantage to participating in the early processes; only in Hargeysa did the practice of vote-buying start.

Who pays, pulls the strings. If the international community had recognised the independence of Somaliland and supported its peacebuilding and statebuilding processes from the outset, the outcome would likely have resembled the federal government in Mogadishu. It should be obvious that state-formation in Somaliland has succeeded because of the absence of external state-building support, not despite it[20].

We shall now examine some of the main characteristics of donor policies and end by asking whether external assistance is not leading to the creation of a rentier state.

Negating local realities and self-governance capacity

There is a puzzling tendency in the entire international assistance sector – including NGOs – to negate local realities. In-country expertise and local language capabilities are not considered an asset in most recruitment processes, to the contrary they seem to be a liability[21]. Instead, technical knowledge of the field of intervention is desired, especially of a comparative nature. Knowledge of local realities is further made difficult by trends over the past decade that affect international agencies, diplomats and NGOs alike, some of which are even starting to affect journalists and academic researchers:

- security risk management policies prevent access of international staff to areas marked as risky by insurance companies and personnel departments

- From a capacity-building perspective, donors prefer local NGOs and organisations to implement programs, rather than internationals

- Rapid personnel rotation from one theatre of conflict or development to the next has become common human resources practice, to avoid international staff becoming partial actors.

- Personal relations between international staff and the local staff and population have become a liability to organisations, sometimes leading to scandals (notably sexual harassment and exploitation) and thus are strongly discouraged. Only contractual relations are desirable.

This disincentivises staff of international organisations and NGOs to acquaint themselves with the local situation. Whatever they do learn may soon be lost as they move to another theatre of operations.

The world of international development and humanitarian assistance lays claim to universalism. When the approach based on best universal practice fails, that might lead to tweaking the approach; but it often leads to denial instead, where the approach is upheld and local reality is blamed for ‘not being ready yet’. Culture is often the culprit. Since for the reasons mentioned above that local reality and culture is unknown and generally ignored, this leads to assumptions about it that fit and reinforce claims to universality. For example, that ‘the anarchist nomadic nature of Somalis makes it difficult for them to accept principles of good governance based on the common good’. This fits the anti-nomad pro-state discourse that has been current since the dawn of history[22], lays the blame on cultural traits that can be overcome by modernisation, reinforces the need for ‘good governance’ and generally comforts the international aid worker that she/he is on the right track, despite adverse results of her/his action.

We can now examine a few examples to see what the effects are of this tendency to negate local realities in favour of general assumptions, with three examples.

Security Council Resolution 814 of 26 March 1993 gave the UN a mandate to assist in political reconciliation and to help build local institutions and administration[23]. The United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM) set out to build a Somali state from the bottom up, according to prevalent conceptions of a liberal democratic state. The Security Council mandate came during a Somali peace conference organised by UNOSOM in Addis Ababa, where it was decided that a Transitional National Council would be elected after the establishment of local councils; the latter would be organised by UNOSOM itself.

Firmly rejecting the secession of Somaliland, the UN attempted to force Somaliland to let them establish such councils, and even suggested they would send troops to Somaliland to achieve this[24]. They regarded the local peace processes and the resultant government as illegitimate, and firmly stood by this point of view until the end of the mission in 1995[25]. UNOSOM persevered in its efforts notably in Sool and Sanaag, exploiting the perceived dissension among many Dhulbahante. It accepted as representatives of this region any groups opposed to Somaliland’s independence, even when they obviously had no backing[26]. They dealt with ex-President Tuur (who had not accepted his electoral defeat in Borama) as the representative of the SNM, even though the movement had disbanded at the end of 1992. Tuur joined General Aideed’s government in Mogadishu and declared Somaliland was reuniting with Somalia. UNOSOM’s political affairs officers reported falsely to the Secretary General that most Somalilanders desired national unity[27].

This total disregard for successful local governance processes failed to derail the formation of Somaliland[28]. It led to outrage among the supporters of Somaliland, but it can be understood in the light of this claim to universality, where any political processes that do not fit the liberal democratic model are deemed illegitimate. It has been a remarkably consistent approach over the past decades.

A more recent example, albeit a small and at first glance insignificant one, can be found in the reaction of international donors to the national development plan process in Somaliland. Consultants assessing the first national development plan recommended that in the elaboration of the second plan ‘local consultations’ should be held to align the planning process with local requirements and to improve local buy-in in the implementation of the plan[29]. They specifically mention the participation of youth, women and minorities. This rests on an assumption that local society has no other means to make its priorities known than through the establishment of formal consultation mechanisms. There is also an implicit assumption that women, youth and minorities have separate priorities which must be ‘heard’ in the framework of a planning process orchestrated by the central government, suggesting dissension and in a way actively encouraging it. Finally, it apparently believes in an equivalent status between the voices of elders and those of politically less mature groups.

For anybody acquainted with Somali internal consultation processes, these assumptions are wrong and potentially destabilising, but also demeaning toward local culture. Despite the occasional lip-service to cultural diversity, almost all international development and assistance programs share the objective of social change – such as through obligatory ‘gender mainstreaming’. That change can only lead in one direction: for ‘them’ to become more like ‘us’, validating accusations of enforced modernisation. In the process, we fail to see how local consultative processes do work and provide the basis for a type of governance which manifestly manages to preserve social peace.

A third example which illustrates the effects of ignoring local self-governance processes is provided by the export of a citizens’ crime alert texting system used in Kenya to a district in Hargeysa. This project was the culmination of several forward-looking ‘best practices’ in the world of development: using information and communication technology to improve ‘democratic policing’; the latter basically means increasing citizens’ trust in their government (and thus improving governance) by making the police more responsive and accountable to the citizens. A law-and-order project thus becomes a vector for social change. It assumes the state needs to build the trust, that the police want to ‘protect and serve’ and that citizens need the security the police can provide[30]. These three assumptions don’t hold. As we saw before, Hargeysa’s citizens monitor possible criminal activity through other means (neighbourhood delegates) and the police seeks to be feared, not loved. As to the state, it is satisfied with current trust levels of Hargeysa’s citizens. The boxes of mobile phones were last seen unused in Maxmud Haybe police station; undoubtedly, they’ve been put to good use since then.

Given that security is such a prime concern for the international community, especially in its dealings with Somalia, it is surprising that there is no effort to understand how local security arrangements work. As seen above, the international community did not understand why there was no piracy in Somaliland, assuming it was the result of a successful monopoly of violence by the state. Negating local reality, replacing it as it were with untested assumptions rooted in an ideological worldview, may be dangerous. Elsewhere, I argued that the post 9/11 assumption that Somalia, as a failed state, was likely to become a base for international terrorism, led to policies that favoured the rise of Al Shabaab and other radical Islamist movements.

In this context, one can understand why some informed observers reach to conspiracy theories for an explanation, especially when they’re on the receiving end of such policies. Disregarding such theories, two options remain: sheer stupidity, or the willingness to pay a high price. But for what? This is one of the essential questions of this thesis, but I will put it aside for now, to pursue my line of thinking.

Of the Uses and Purposes of Institutional Mimicry

The language of the National Development Plan II is uncannily similar to that of the World Bank: the goals given on page 1 are to “reduce poverty”… “increase resilience” … and “maintain the human rights of every citizen”, and other obligatory buzzwords are also there: economic opportunities, climate change, good governance etc. The national plan is divided into 5 ‘pillars’, 9 ‘sectors’ and 3 ‘cross-cutting themes’, and each sector and cross-cutting theme has a ‘vision’ and ‘objectives’ which are divided into ‘ ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ with in total 223 measurable indicators. For example, in Pillar 3 ‘Good Governance’ one finds five sustainable development goals; one of them, ‘SDG16’ has the following 18 measurable indicators:

SDG16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

1. By 2021, reduce 50% of all forms of violence and related death rates everywhere

2. By 2021, increase effectiveness and efficiency of rule of law at the national level and ensure equal access to justice for all by 70%

3. By 2021, reduce the level of homicide and injuries emanating from illegal possession of small arms and light weapons by 50%

4. By 2021, reduce of all forms of organized crime by 50%

5. By 2021, Somaliland will have maritime security policies, laws and institutions in place and can assert control and sovereignty over its maritime domain

6. By 2021, achieve zero tolerance of corruption and bribery

7. By 2021, Develop effective, accountable and transparent public institutions at all levels

8. By 2021, the Government of Somaliland will ensure that 100% of public workers are recruited through the formal and merit-based process

9. By 2021, review the structure and the functions of public institutions by 100%

10. By 2021, Somaliland will reform country’s budget model and budgeting processes

11. By 2021, enhance public/community participation in decision making process of all national matters

12. By 2021, develop national communication policies and strategies for promoting access to

information and community engagement

13. By 2020, amend and develop media sector regulations and develop media quality Standards

14. By 2019, increase the percentage of citizens with national ID (i.e. regions, districts, rural and urban, gender, and ages) to 50%

15. By 2021, Government of Somaliland will reduce human rights violations through devising robust human rights violations monitoring systems and mechanisms

16. By 2021, eliminate all forms of terrorism and piracy crimes to zero

17. By 2021, significantly reduce all forms of discrimination against all women

18. Eliminate national and local election delays to zero

There is no doubt that no-one in either the government of Somaliland or among the donors believes that more than a fraction of these objectives can be achieved. Instead of a plan, this document is a formality, destined to unlock the second contract of the Somaliland Development Fund and ensure that virtually any activity the government undertakes fits in the general framework. In the hope that the regions would also receive international support[31], regional development committee plans were made, but without consulting with the districts or trying to harmonise with the national development plan. The regional development plans are written in English and serve no purpose, as admitted in the National Development Plan 2017-2021, as regions have no implementation capacity and do not coordinate with central government agencies or districts[32]. The inescapable impression is that local, regional and national government agencies produce plans mainly to extract rent from them. The external consultants found that awareness of the plan was minimal outside the central ministries[33].

The Somaliland Development Fund’s mandate is to build the government’s capacity through on the job training, where it assists the government agency (usually a ministry) in charge with externally hired consultants, but let the government lead at all times and uses ‘country systems’[34]. It takes charge of the often-complicated project management and reporting, while teaching the agency in charge of the overall project to deal with these complicated issues[35]. It is led by capable Somalilanders with a diaspora background, and only rarely hires a foreigner. In terms of donor-assisted state capacity development, it is seen as embodying current best practices, and the SDF has become a ‘donor darling’. Just like IMF and World Bank ‘staff monitoring programs’ the Somaliland Development Fund’s main task is to teach Somaliland’s authorities to work in the way preferred by donors.

Its focus on process (government decision-making and capacity building according to the donors’ latest standards) over content is obvious when one considers the first batch of infrastructural works that are supported under the SDF-2 facility[36]; these include rebuilding the road from Berbera to Burco, improving the running water supply of Hargeysa, building a pier for fishers in Maydh and soil conservation and agriculture. The road is maybe the best one existing in Somaliland and carries little traffic[37]; many donors have already contributed to the water supply of Hargeisa with meagre results and a high level of alleged corruption; and for lack of cold storage, fish processing and roads the fishing pier will only be able to serve a population of about 2,000 (and one of the two bases of Somaliland’s Coast Guard, but that was not mentioned in the communiqué)[38]. Apart from the fourth project, about which no details were given, this group of projects cannot reflect the true priorities of Somaliland’s infrastructural needs[39]. Instead, they seem to reflect the requirements of certain powerful members of the state-elites to access funding for altogether not very necessary projects.

From a Somaliland state perspective, the international funding channelled through the SDF may be politically useful indeed, broadening the state elites by including new groups (such as the Habar Younes subclans residing in Maydh) while ensuring that core state elites receive a fair chunk of the funding through legal means (e.g. contracts, security provision, agency overheads, recruitment). The funding will thus consolidate peace by further cementing state elites’ solidarity, which as we have argued provides the social foundation of the state. But for the many Somalilanders left out of the process, it may simply seem money ill-spent and feeding corruption.

This view from outside the elite compact, just like my own initial reaction, makes the mistake of taking the stated objectives at face value, e.g. responding to Somaliland’s most pressing infrastructural needs. Or to believe, using the donors’ public relations vocabulary, that the purpose is ‘strengthening the capacity of the state to deliver essential services to the population in an accountable and transparent manner, thus bolstering its legitimacy’. The donors’ focus on process and form reveals an underlying objective: a meta-objective underlying donor programs with differing objectives. The funding, as just argued, does serve the goal of strengthening the political compact at the heart of the state, in the same manner as this happens with public money in Europe[40]. Little does it matter that the road is not necessary; what matters is that senior civil servants from each ministry came together countless times, under SDF guidance, and learnt how to manage this process; that the Ministers managed to prioritise projects and accept that some would be selected and others not; and that at least one project takes place outside the heartland, bringing new members into the state compact.

Funding government projects with so many conditionalities serves the grand purpose of moving the source of legitimation of the state from the charismatic to the legal-rational, to use Max Weber’s concepts[41].

Two conflicting or complementary modes of legitimation

In this situation, the Somaliland politician must reconcile his charismatic leadership with his institutional, legal-bureaucratic one, as both are expected from him. His lineage members and rural voters may expect the former, his urban voters, broader civil society and international partners expect the second. On one side it is expected he will hand out cash, mobile phones and government positions; on the other a strategic vision is expected, party discipline and strictly lawful and generally irreproachable behaviour. In the morning he puts on a suit and tie and speaks English in the office; in the afternoon he dons a macweys and chews qat with his lineage members. It would be interesting to study how the political language has evolved over the past decades. Without a doubt, utterances of politicians and senior civil servants are quite different depending on whether they are made in English or Somali. Anticipating on the results of such a study, politics within Somaliland seem to still be based on charismatic legitimation.

One purpose of international assistance

What is certain is that international assistance is pushing state elites to adopt the legal-rational mode of legitimation. Siad Barre may have made some structural adjustment reforms on paper and received large loans from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank in exchange, to spend as he saw fit. This didn’t affect his capacity for charismatic rule. But those times are over. Modern governance requires strict and detailed compliance instead of inspired leadership, and the technical-bureaucratic mindset of an expert instead of flexible politicians’ skills. Power comes from above (the international community), not below (the people), and depends on position, not capacity. Given the lack of political alternatives, apart from radical Islamism, it seems that Somaliland, Somalia and all other ‘developing’ regions of the world only have one direction to evolve in. In my discussions with educated Somali youth this conscience that there is no alternative was expressed clearly. For example, most clearly saw the shortcomings of a ‘winner-takes-all’ electoral democracy model, in comparison to consensus-based ‘traditional’ decision-making. But none of them took my suggestion of a return to the latter model seriously; one-man one-vote elections in a multiparty democratic system are the only way forward, however disruptive they may be.

Is Somaliland becoming a rentier state?

“If all international funding were to be withdrawn tomorrow, entire sectors of Somaliland’s state would collapse – most notably, health and education”[42].

A rentier state focuses on extracting ‘rent’ from the international community without needing to develop the domestic economy. Although the term was first used for the oil-rich Arab states, it has come to be used more generally for any state whose elites seek to generate external revenue rather than domestic revenue. This allows them to stay in power without reorganising or developing the domestic economy, thus potentially losing popular support[43]. Is Somaliland becoming a rentier state?

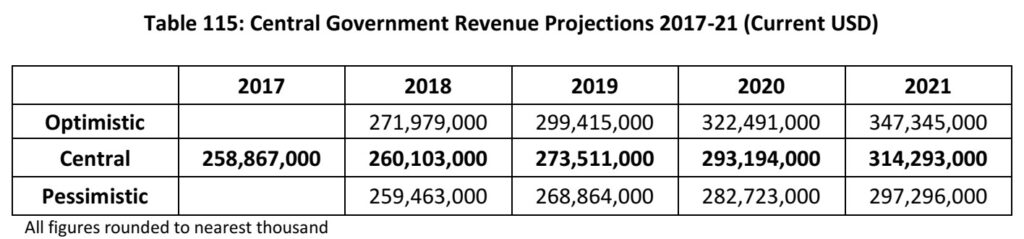

At first glance that seems impossible. A look at the national budget indicates there is no external revenue, only domestic revenue. Of course, since the state is not recognised, it cannot borrow on international markets. At second glance, the Ministry of Planning admits more than a hundred million dollars per year of external aid, amounting to nearly 50% of government revenue in 2017. However, this figure excludes humanitarian aid to Somaliland and all aid that accrues to Somaliland through Somalia-wide aid provision, which as we noted above is considerable. A fair chunk of the approximately 1 billion $ yearly humanitarian aid for Somalia[44] is spent in Somaliland. Therefore, though it is hard to find exact figures[45], it is likely that external aid surpasses government revenue.

All three tables below extracted from Somaliland National Development Plan 2017-2021

2017 expenditures by sector in USD millions.

Note that 2017 was an elections year, hence the high governance expenditures.

Now if one takes into account the wishes of Somaliland, as expressed through the National Development Plan[46], the proportion of aid to national revenue increases drastically. In the 2012-2016 National Development Plan, it was expected that the government would contribute 6.2% of the requested 1,190 million USD, and external donors were expected to contribute 82.3% (the rest to be contributed by the private sector – 11.1% – and the diaspora – 0.3%) while the 2017-2021 National Development Plan expects only 3.8% of the requested 2,112 million USD to come from the government (it does not specify where the rest of the funding should be sourced from, but clearly external donors would have to foot most of the bill).

Of course, the national development plan is but a wish-list and most of the 2012-2016 plan was not funded[47], but it does indicate Somaliland’s aspiration to become more of an external rent-seeking state, as opposed to mobilising domestic resources.

International assistance is influencing the development of Somaliland as a rentier state with entrenched state elites. This happens in several manners:

- international assistance discharges the state of providing essential services to the population

- it provides direct income to state elites

- it deepens the relation of dependency to the international order

First, the international community discharges some of the functions of the state in its place, thus freeing government resources for other matters such as security. In the education, health, livestock and agricultural sectors the government does not do much more than pay salaries; almost all other costs are paid by international donors[48]. In the last table above, the international community outspends the government in six of the twelve sectors, including health, water & sanitation (WASH) and economic/productive/energy & extractives. In this sense, rhetoric aside, the state of Somaliland is not self-sufficient, but depends on international support to boost its legitimacy among the population. This legitimacy is mostly boosted in the heartland, where almost all aid is delivered. On the other hand, the small scale of aid in East Somaliland and Awdal beyond Borama confirms local populations’ views that they are neglected by the state elites and the international community[49].

Second, the considerable funding flows allow multiple points of resource extraction, e.g. capturing contracts, overpricing, imposing security arrangements, receiving stipends and plain embezzlement. This rent may have become the main source of income for many members of the state elites, from civil servants to private businesses. As noted above, it also allows for the expansion of the state elites. Foreign money in a way does not belong to the people and can be ‘captured’ and disposed of more freely than, for example, tax income. Nevertheless, Somalilanders generally consider the entire aid sector as abetting corruption and suspect that it is itself also corrupt[50].

Third, the prestige of dealing with international partners also provides a rent of sorts, as people are not only motivated by money. It bolsters one’s standing in local society[51] while providing new opportunities through access to the higher spheres of power, especially if exposure is lengthy enough (when a Somaliland official establishes, for example, personal relations with diplomats or fund directors).[52]

We can conclude that Somaliland’s state developed solid roots in society because of the lack of international assistance during the first fifteen years; this obliged the budding state elites to search for support among social forces in the country, and gradually expand the social compact underlaying the state using domestic resources. International assistance has steadily increased since the mid-2000s, to the point that external assistance is probably equal to or more than government revenue today. This allows Somaliland’s state elites to increasingly capture rent but has put the state of Somaliland in a dependent relation with the international community; in short, Somaliland is becoming a rentier state, not unlike many other African states. A point of enduring conflict remains that the international community does not recognise Somaliland’s independence; this hampers the full assimilation by Somaliland’s elites of the international discourse regarding statehood.

The Somaliland Development Fund signalled a qualitative shift away from earlier external assistance, as funds are now directly routed through the government, in an attempt to modernise its functioning; this may be seen as an effort to change the style of governance in Somaliland from charismatic to legal-rational. It also strongly supports centralisation, undermining local self-governance. It is but one of the ways in which external assistance seeks to effectuate social change, without an effort to understand how local governance works. This blindness to local sociocultural systems may turn out to be dangerous. State elites are on the cusp between both systems (the international and the local), and by becoming dependent on external rents they are increasingly becoming a transmission belt for the values underpinning the global state model. A rift is growing with their constituencies because of the denial or downplaying of the rhizomatic lineage-based politics that has brought them to power.

Quest for Recognition

Why is Somaliland not recognised as an independent state? And what difference does it really make?

Problems of non-recognition: not possible to travel on a national passport, no letters of credit for businesses and generally problems of integration in the world of global finance (no SWIFT code facilitating transfers). Somalilanders have manifestly found ways to deal with these practical disadvantages, because they do business abroad and travel too[53].

Also symbolic problems: Somaliland no member of the concert of nations, no influence in international organisations. But the greatest disadvantage is that Somaliland’s government cannot access international funding. Soon Somalia may start borrowing again, from the IMF, the World Bank, the African Development Bank and other international financial institutions. But not Somaliland. The European Investment Facility has been looking into options in Somaliland, but it cannot move forward as it would have to go through the federal government, which is sure to block it.

On the upside, Somaliland has no debt.

Also popular pressure: Somaliland’s authorities must be seen, by the population, as at least advancing on this front; recognition will be the crown on the process of state formation[54].

External analysts almost all agree that Somaliland should be recognised. They advance arguments of different sorts:

– legal: Somaliland ticks all the boxes for statehood and there are enough precedents (Senegal seceded from Mali, Gambia from Senegal, Cape Verde and Guinea Bissau split). Moreover, the parent state Somalia is not even able to exercise sovereignty over Somaliland (see Puntland and problems with the FMS). Extensive legal argumentation by Schoiswohl[55] also concludes that Somaliland, as a de facto state, is bound by international treaties[56].

– political: recognising Somaliland would (putatively) strengthen its democratic system; offer a positive example to other states in Africa, notably Somalia; it will not upset the African Union’s sanctity of borders (an AU commission argued that Somaliland should be recognised)[57] as thirty years would be too long for any candidate to wait; to support SL in the war on terror[58];

– moral: Somaliland has done its best to become a responsible member of the international community, and it should be rewarded after 30 years of good governance and democratisation, fighting terrorism and being, in other ways, a ‘good member of the international community’.[59] This was the course also followed by Somaliland, notably through the establishment of a constitutional multiparty democracy. But as Richards notes, “Worthiness alone is unlikely to garner a political entity sovereign statehood status”[60].

But none of these arguments make any difference. The international community will not recognise Somaliland because it has no interest in doing so. In fact, it only recognises new states when powerful states themselves want it, typically as part of a peace solution after a bloody war (South Sudan, Eritrea) or to pursue their own interests (dismemberment of Yugoslavia, stopped at the limit of Kosovo. Internal legitimacy makes no difference; statehood is only conferred as a sign of external recognition[61], just like knighthood. Only the powerful members of the international state order can confer statehood on others.

Recognition once granted is never withdrawn. As the case of Somalia demonstrates, even if a country has not exercised statehood for decades, it remains a state. There is no process or precedent for losing statehood (except through break-up into multiple states). There is perhaps no more stable institution in the world than the state.

However a state need not be recognised as a state for other states to engage it. The category of de facto state[62] – think of Taiwan, Palestine, Kosovo, Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq – is an increasingly permanent feature of our state system[63]. It gives a state the obligations but not the rights of states – for example, they must still observe human rights. The diplomatic rapprochement between Taiwan and Somaliland, which led to the announcement of the opening of a diplomatic representation by each country in the other in June 2020, is another sign that ‘de facto’ states are in the process of being normalised[64].

Somalilanders often blame their own authorities for failing to gain recognition. Here are some of the criticisms levelled: the narrative is not developed, there is no long-term strategy, no resources, lack of persuasion skills and techniques. Somaliland has no military, political, economic or cultural leverage to apply, can only try to persuade through attractiveness[65].

Non-recognition better for social cohesion[66]. Somaliland not a ‘nation-state’: Non-Isaaq not well integrated into the state. Problems over border with Puntland. Somaliland not ready for international recognition, would reinforce predatory and corrupt behaviour of elites.

[1] Which was not under UNOSOM and could thus stay in the country

[2] Interview with EU assistant Adnan Hagoog.

[3] I asked the Netherlands ambassador to Kenya and Somalia Frans Makken why the Netherlands did not push for recognition of Somaliland. He mentioned that it would be wasting political capital for an issue no-one cares about, and which would bring the Netherlands little benefit. He also noted that Somaliland was doing well without recognition, joking that it was maybe because of non-recognition. Interview September 2017.

[4] Bryld ea. 2016. They note that since the objectives of the national development plans (I & II) are so all-encompassing and not prioritised, almost any NGO activity will fit in its framework.

[5] For reasons explained in the chapter on Somalia: the expulsion of the Union of Islamic Courts led to a major effort to stabilise Somalia as a potential new battlefield in the War on Terror, leading to a surge in assistance.

[6] Somaliland Ministry of Planning, 2011; henceforth ‘Vision 2030’.

[7] See the critical appraisal by Bryld, Kamau & Farah, 2016: “External Review of the Somaliland National Development Plan”

[8] “As one development partner [donor] stated, ‘the current or any future development plan for Somaliland is unlikely to have any major influence on our development priorities’.” Bryld ea. 2016:13.

[9] Obviously, the Federal Government of Somalia is not eager to sign off on funding that boosts Somaliland’s government or its independence. Bryld ea. 2016:25.

[10] E.g. Bradbury, Abokor & Yusuf (2003), Reno (2003), Kaplan (2008), Battera (2004), Drysdale (1992), Hansen & Bradbury (2007), Hoehne (2011), Johnson & Smaker (2014), Philips (2016), Renders and Terlinden (2010), Richards (2014) and Walls (2009).

[11] Some authors such as Seth Kaplan solve this contradiction by stating that self-reliance was important in the formative years, but to grow beyond a clan-based political system into a full-fledged liberal democracy, recognition and external support are needed (Kaplan: Fixing Fragile States, 2008:123-124). This reasoning is only valid if one accepts the teleological point of view that only one outcome of the statebuilding process is possible, namely liberal democracy.

[12] ‘Voting is fighting. Let’s opt for consensus’ one elder at Borama said. Cited in Academy for Peace and Development & Interpeace 2008, ‘Peace in Somaliland: an indigenous approach to statebuilding’ p. 52

[13] Ibidem p.52

[14] Phillips 2016:639

[15] The author had a first-hand experience of this as political affairs officer for UNAMA in the transition to the post-Taliban regime, 2001-2003. We were building institutions through which Afghan politics could be channeled in a peaceful manner, and becoming involved in local politics was a sin which cost some of my colleagues and me our careers in the UN.

[16] Philips 2016:640

[17] Richards 2014:31

[18] Timothy Sisk in “Statebuilding” (2013) gives a clear exposition of the statebuilding doctrine: “Statebuilding has become an overarching concept to security and development in fragile states that envisages the improvement in governance institutions and processes at the national and local level as a way to channel and manage social conflicts away from the battlefield or streets and into regularized processes of non-violent resolution of social conflict through professional public administration, elections and parliamentary politics, and through participation and voice of citizens.” (Sisk 2013:1)

[19] Ashraf Ghani & Clare Lockhart: Fixing Failed States: a Framework for Rebuilding a Fractured World, 2008

[20] Richards 2014:181

[21] Based on personal experience: decades of experience applying for jobs.

[22] See James Scott: “Against the Grain” 2017.

[23] Richards 2014:31. This was the first instance where the UN explicitly included state-building in its response to a crisis.

[24] UNOSOM’s Head of Political Affairs Leonard Kamungo, when threatening President Cigaal with this option, was given 24 hours to leave the country. See Renders 2006:250-251

[25] ibidem p. 253

[26] Such as the United Somalia Party, a political party that had dissolved in the early 1960s and was resurrected by political entrepreneurs from the Darood for the purpose of representing the Harti in Somaliland at the negotiation table.

[27] The Report by the Secretary General on the Situation in Somalia of 17 September 1994 stated that factions from Somaliland meeting in Garowe had declared that ‘the secession of the north was neither feasible nor desirable’, pretending that these factions represented majority opinion in Somaliland. It has been suggested that the UN Secretary General, the Egyptian Boutros Boutros Ghali, supported Egypt’s consistent efforts to keep a strong and united Somalia as an adversary to Ethiopia, Egypt’s historic rival in Nile water management.

[28] Ten years later a similar process occurred in Iraq, where the downfall of Saddam Hussein’s regime had led to the election of local councils that successfully governed local affairs until the Coalition Provisional Authority of Paul Bremer declared null and void those councils and proceeded to replace them with hand-picked tribal elders in its effort to ‘de-Baathify’ the country.

[29] “The process should ensure to involve discussions across all regions of Somaliland and involve marginalised groups and clans as well as special emphasis on the voice of women and youth. Material produced before and after these sessions must be made available in Somali.” Bryld ea. 2016:30

[30] Hills, Alice 2017: “Is There Anybody There? Police, Communities and Communications Technology in Hargeisa”

in Stability: International Journal of Security & Development, 6(1): 6, pp.?1–16 p. 5. On the aims of ‘democratic policing’ she quotes Findlay and Zveki? 1993:33.

[31] “One additional criticism was by the regional governments who appeared to have been bypassed in the decision-making process for [SDF] projects implemented in their locations. The representatives from the three regions visited all had the same complaint” Bryld ea. 2016 p. 26

[32] MoNPD 2017, National Development Plan II 2017-2021 pp. 300-301

[33] Leading them to formulate the recommendation that the plans should be translated into Somali.

[34] This is development jargon meaning that aid is channelled through governments, instead of through parallel structures outside of government.

[35] Contracts run into the hundreds of pages, the SDF secretary told me (Interview in Hargeisa)

[36] See “Somaliland: Denmark, Netherlands and UK Announce Funding for Infrastructure” published on 8 July 2020 by the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples’ Organization: https://unpo.org/article/21973.

[37] Personal observation. I took this road at least ten times, also driving myself.

[38] Review of Maydh produced by my organisation, directed and edited by me in 2017.

[39] Off the top of my head, these would be improving the road from Hargeisa to Djibouti, capturing flash flood water, providing the infrastructure for low-level industrial processing and manufacturing etc.

[40] Think of the astronomical amounts of public money that are ill-spent on unproductive administration (e.g. the European Union or new layers of management to oversee public services) or overpriced and unnecessary public contracting works (such as building a new motorway where none is needed or transforming each intersection into a roundabout). These expenses also strengthen the social compact underlying European states (e.g. big business and high salaries to people that belong to the elites, regardless of output).

[41] Weber 1919 “Politics as Vocation”. A short explanation of the different sources of legitimation…

[42] Adnan Hagoog, veteran assistant of diplomats working in Somaliland, interview in Hargeysa 8 May 2019. When I interviewed him he worked for a small team of European consultants who informally represent the EU in Somaliland.

[43] Beblawi, Hazem, 1987: “The Rentier State in the Arab World” in Arab Studies Quarterly 9 (4): 383–398.

[44] According to OCHA, from 2017 to 2019 the humanitarian funding received is more than 1 billion $ per year. Before that it was less.

[45] The only way to find out how much international assistance goes to Somaliland is by looking at the breakdown of each humanitarian and development organisation working in Somalia, and extracting only those activities undertaken in Somaliland. But such data is not generally available.

[46] Let alone the Somaliland Vision 2030 document, which estimates more than 11.5 billion dollars are needed to achieve Somaliland’s sustainable development goals.

[47] According to an early survey by the Ministry of Planning, 39% of the outcomes planned in the first National Development Plan were achieved by 2016. Given the gap between the ambitious goals and the funding shortfalls, this seems a high success rate, which may not stand scrutiny.

[48] Interview with Adnan Hagoog confirmed by NGO directors. “In education, the SL government does no more than pay the teachers’ salaries; all the rest – buildings & furnishings, textbooks, school lunches, teacher training, stipends – is provided by NGOs. In health it’s much the same”

[49] Agencies operate in most Dir and Isaaq places areas but rarely in Dhulbahante and Warsangeli areas, because of perceptions of bad security. And the further away from Hargeisa, the less aid. Observation of the author when working for the NGO community in Somaliland.

[50] Discussion with countless Somalilanders of different backgrounds. The reputation of NGOs, in particular, is very bad. Local NGO staff drives around in big cars and lives in big houses, forming a separate cast of the elite.

[51] Whenever I, a low-ranking but white NGO official, would meet a mayor or governor in far-flung districts an official photo or video would be made, and promptly published on local media channels.

[52] In neo-Gramscian terms, international elites spread the hegemony of the transnational class by absorbing new members at the local level, who seek to adapt their values to the hegemonic ones (liberal democracy, Rule of Law, human rights, nuclear families, relations between people governed by contracts, the inviolability of private property, etc.) and thus become transmission links – as symbols of success – toward their own societies, reinforcing the hegemony of the transnational class in the process (see Stephen Gill ea.). I believe that this is the true objective of international assistance; this grand objective justifies the loss of billions of dollars in efforts to (re-)structure states in the developing world. It is to make the world comply to one hegemonic system, thus making it readable and facilitating domination from the centre over all the peripheries.

[53] My sources told me a Djibouti passport can be obtained for 1500 USD, Ethiopian ID needs political or clan connections but can be obtained. Each Somalilander, being officially a citizen of Somalia, can also apply for a Somali passport in Garowe, but its international acceptance is minimal.

[54] Interview Ali Khalif Galaydh

[55] Schoiswohl 2004: “Status and (Human Rights) Obligations of Non-Recognized De Facto Regimes in International Law: the Case of ‘Somaliland’.”

[56] Schoiswohl 2004:307

[57] The African Union’s fact-finding mission declared that Somaliland’s status was ‘unique and self-justified in African political history,’ and that ‘the case should not be linked to the notion of ‘opening a Pandora’s box’; quoted in Eggers 2007:220. Alison K. Eggers: ‘When is a State a State? The Case for the Recognition of Somaliland’ in Boston College International and Comparative Law Review Vol 30, 2007 pp. 211-222

[58] The former representative of Somaliland to the USA, Saad Nur, warned shortly after 9/11 that if Somaliland were further denied international recognition “The forces of darkness will gleefully celebrate the eclipse of the only secular democracy in the Somali-speaking region of the Horn and feverishly try to fill the vacuum by establishing a Taliban-like regime. . . . The crescendo will come to a thunderous roar if the coveted southern shores of the Gulf of Aden . . . fall under the control of an organisation like the one that blew up the USS Cole” quoted in Huliaras, Asteris: ‘The Viability of Somaliland: Internal Constraints and Regional Geopolitics’ in Journal of Contemporary African Studies, Vol. 20 No. 2, 2002 pp. 157-182; on p. 173.

[59] Johnson & Smaker 2014:5-6 basing themselves on Caspersen 2012:69–70

[60] Richards, Rebecca, 2015: “Bringing the Outside In: Somaliland, Statebuilding and Dual Hybridity” in Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Vol 9, No. 1, 4-25’; p. 5

[61] Tilly, Charles – War Making and State Making as Organized Crime in Evans, Rueschemeyer & Skocpol, eds: Bringing the State Back In, 1985, pp 169-191

[62] According to Scott Pegg’s definition, de facto states “feature long-term, e?ective, and popularly supported organized political leaderships that provide governmental services to a given population in a defined territorial area. They seek international recognition and view themselves as capable of meeting the obligations of sovereign statehood. They are, however, unable to secure widespread juridical recognition and therefore function outside the boundaries of international legitimacy[62].” Pegg, Scott: “International society and the de facto state” 1998, p. 4

[63] Caspersen, Nina and Stansfeld, Gareth, eds:“Unrecognized states in the international system”, 2011; Introduction.

[64] Garowe Online: “Somaliland and Taiwan sign deal to open consulates in their territories”, 01 July 2020. Link.

[65] Inteview with Prof. Samatar

[66] Interview with Adnan Hagoog