Analysis by Robert Kluijver, April 28 2021

The crisis that is rocking Somalia now is caused by the unwillingness of President Farmajo, whose term ended on Feb 8, 2021, to allow a transition of power. If he continues to cling to the presidency, we may witness a disintegration of national security forces into clan-based militias that defend certain areas of Mogadishu, resulting in low to medium levels of armed conflict and permanent instability. The fragile political progress made over the past decade may unravel and the Somali economy may enter a phase of stagnation or decline. Mogadishu residents fleeing their homes to escape the fighting (60,000 to 100,000 on Sunday April 25, according to the UN) and the Al Shabaab attacks in Mogadishu on April 28 are a foreboding of what may come if this crisis is not rapidly resolved.

In the night of Tuesday to Wednesday 28 April, Farmaajo announced he would seek a new mandate from Parliament to solve the current political crisis through elections, overturning his earlier insistence that the extension of his mandate by two years, voted by the Lower House on 14 April, provided sufficient legitimacy for his rule. In the same speech he lashed out at his political opponents, accusing them of engineering the current crisis for their personal benefit. Far from conciliation, he did not suggest he would step down to allow a level playing field during the electoral process, which is a key demand of his opponents.

Balance of power

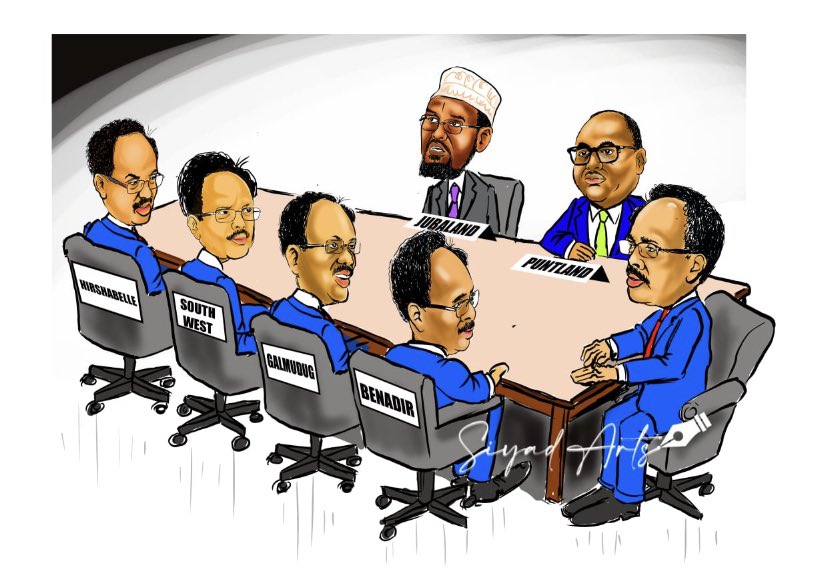

His opponents are members of the Mogadishu-based political class, and two of the five federal member state presidents. While the former seek to win through a fair electoral process, the presidents of Puntland and Jubaland seek to increase their autonomy from the central government. What’s at stake is the repartition of economic resources and political power between the centre and the regions, a conflict which has marked Farmajo’s entire term (2017-2021). The constitution should indicate how resources are shared, but the constitutional process is stalled because of this fundamental disagreement. Farmajo has attempted to increase the share of central government, and over the past years has spent considerable political capital engineering the election of presidents in South West State, Galmudug and Hirshabelle who support him. He has also attempted to create a new political base favourable to him in the capital Banadir region, against the provisional constitution of 2012. The Banadir governor thus obtained a seat at the table in the last, inconclusive rounds to prepare indirect elections before Farmajo’s mandate ran out.

Farmajo opposed the re-election of Ahmed Madobe in Jubaland, declaring his victory in the state’s 2019 elections illegal. He sent army units to Gedo, which is part of Jubaland, but which has now effectively come under Farmajo’s administration, after the defection of Jubaland’s regional commander to federal forces.

At the central level, Farmajo has strengthened his hold over the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) and the media sector, and he has stacked the Federal Electoral Implementation Team, which is to oversee the electoral process, with his allies – many of whom don’t even respond to the required profiles. This gives him an unfair advantage over his electoral opponents.

Parliament is divided. The Lower House has a pro-Farmajo majority, although this can change as there is no party discipline (there are no effective political parties) and each member of parliament votes according to his or her own interest; votes are often bought or traded for political advantage, and Farmajo has more resources than his opponents. The Upper House, whose members are directly appointed by the member states, is in its majority against Farmajo. The ‘law’ extending Farmajo’s presidential mandate adopted in the Lower House on April 14 did not pass through the Upper House before he signed it, and thus is not valid. By ignoring the Upper House and suggesting the non-federal entity Banadir region appoint 13 senators (allowing him to tip the balance in his favour) he has turned this institution against him.

Background

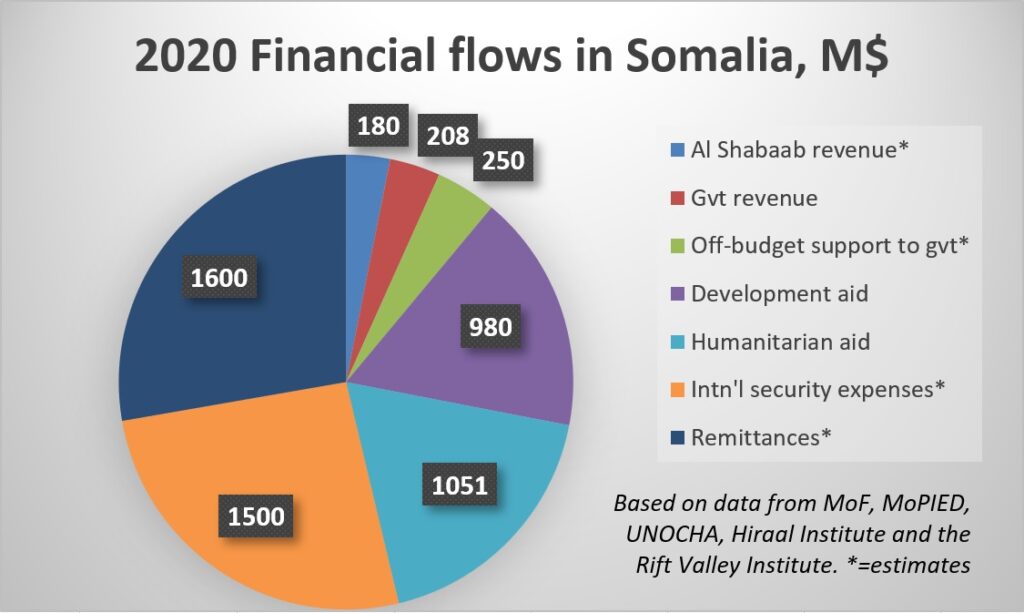

The Federal state that has emerged since 2004, in a slow and halting process, is mainly a conduit for international aid and political support. Revenue of the government stood at 208 million USD in 2020 (data from the Ministry of Finance), most of which is earned through the port of Mogadishu. International development aid channelled through the government was more than that (265 M$) and there is a considerable amount of ‘off-budget’ support to the government, provided by Gulf countries, Turkey and neighbouring countries – this is estimated to be at least a few hundred million dollars.

In addition, authorities profit from the roughly 2 billion USD yearly international humanitarian and development assistance funds (according to OCHA), as well as 1.5 B$ spent yearly on security by international partners (estimation of the Ministry of Planning, 2019). In addition, Somalis abroad send an estimated 1.6 B$ per year to their relatives in Somalia. Local sources of revenue are thus dwarfed by external financial flows, and the main object of Somali politics is to manoeuvre oneself into a position to benefit from these flows. According to Transparency International, Somalia consistently scores highest of all countries in the world in ‘perceptions of corruption’.

It may be noted that, unlike in some neighbouring countries, the embezzled funds seem to not primarily serve for personal enrichment (offshore accounts and real estate) but are largely reinvested into the national economy, either to support extensive networks of clan members and allies, or for business ventures, private security and luxury consumption. Vote-buying takes place quite openly in elections and legislative processes. According to the importance of the issue, members of parliament and regional state assemblies can expect from the 10,000s to the 100,000s of dollars for their vote. This in turn allows them to pay for favours among their clan constituencies. This patronage system facilitates the spread of central funding through society.

The rules of the game

This system seems to largely work for the general population, with two conditions. The first is maintaining a high level of international funding. Since the early 2000s international support to Somalia, including state-building support, has been constantly increasing. But with the IMF’s 2020 decision to resume lending to Somalia, the government now has an attractive option. It can replace the resented UN and donor oversight of the Somali state and borrow from international institutions, eventually even on international capital markets. This perspective may explain why Farmajo feels more emboldened than his predecessors to disregard the wishes of his international supporters.

The second condition is a regular reshuffling of roles within the political class. Every four years the political elites vie for new positions. If the President is from one clan family, the Prime Minister will be of another, and the other clan families can count on the positions of speaker of one of the houses of parliament; power ministries and other positions such as the mayor of Mogadishu are similarly shared. While keeping a clan balance, this system does not produce renewal of the political class. Of the four main electoral contenders to Farmajo, two are former presidents, and one was Farmajo’s prime minister.

Farmajo’s refusal to step aside breaks this unwritten rule of Somali politics. That the consensus between clan families was broken and that conflict may be taken back to the streets became clear when opposition politicians left the Jazeera Hotel and their bases nearby and retreated to the areas where their clan resides. Clannism is not the result of primordial identities. The reason why commanders of security forces align behind political leaders of their clan is not blind clan loyalty, much less hatred of other clans, but the perception that they must join forces to obtain a better position for themselves and their kin.

Resolving the current crisis

This dynamic explains why Farmajo withdrew, in the night from Tuesday to Wednesday 27 April, from his maximalist position that he now had a legal mandate to rule another two years. The day of violence in Mogadishu on Sunday 25 April between government and opposition forces, when security forces loyal to the different parties threatened to partition Mogadishu like in the civil war, was caused largely by political leaders from the same clans that dominate the states of Galmudug and Hirshabelle. The presidents of those states, despite being Farmajo’s allies, clearly understood that unless rapid elections cause a redistribution of roles, they will face instability and contestation within their own clans. Withdrawing their support to Farmajo’s mandate extension was dictated by their own political survival.

Under intense international and domestic pressure, Farmajo will now submit to holding indirect elections as agreed in September 2020, but he will only want to do this from his current position of authority, allowing him to determine the outcome. The opposition will, for the same reason, demand his resignation and a change in federal electoral institutions to make them more neutral. One can expect bitter wrangling between the parties, provoking new bouts of instability. It is therefore best for the international community (and the opposition) to insist squarely on Farmajo’s resignation, and the appointment of a caretaker government which could be under current Prime Minister Roble, with the sole purpose or organising elections as soon as possible.

Democracy in Somalia?

An indirect election of the kind that brought Farmajo and his predecessors to power would reproduce the political class and therefore the elite pact that characterised the previous years. But it cannot ensure long-term stability. The objective of one-person one-vote elections that is written into the political code of federal Somalia, and which Somali political elites have in principle agreed to, also seems to be the desire of the Somali population. Somalis generally aspire to a renewal of their political system and the end of clannism, which they openly despise, consistently accusing others of clan politicking while defending themselves of that accusation.

But the experience of electoral multiparty democracy introduced in neighbouring Somaliland in the early 2000s is not encouraging. It has been captured by the clan factor and has led to the entrenchment of existing clan lineage oligarchies, also in the economic sector, causing general stagnation. Somaliland is heading to its own (long overdue) local council and parliamentary elections, scheduled for May 31 this year. It is widely assumed the electoral process has been sufficiently engineered by the elites around President Bihi to preclude a major reshuffling of power. But in Somaliland, at least, there is peace, which is desperately needed in the rest of Somalia, and direct elections certainly seem to contribute to that.

A settlement to solve the current political crisis must thus include a much firmer commitment to holding direct elections than has been the case until now. This would include phasing out the international resources that support the current system, such as the massive amounts paid to Somali business/ warlords to secure the international green zone around Mogadishu airport. The renewal of the political class should come from below, through community elections, building upwards. This would circumvent the main disadvantages of ‘top-down’, centrally organised elections: the cost and the difficulty of implementation. The peaceful, consensus-based, self-supported establishment of the state of Somaliland in the early 1990s may serve as an example of how to conduct such a process.

Besides the general reticence of political elites to submit to the popular vote, the main reason given against direct elections is insecurity: Al Shabaab actively opposes democratic elections as a foreign import. The insurgent group directly controls at least 30% of the federal territory, and shares control over most of the rest of South and Central Somalia, as well as parts of Puntland. Al Shabaab penetration of federal government institutions, including its security forces, is widely known. In Mogadishu, as throughout South and Central Somalia, almost all businesses pay taxes to Al Shabaab. A conservative estimate of Al Shabaab tax collection puts it at 180 million$ per year (Hiraal Institute Oct 2020 report “A Losing Game”). Even the UN admits that Al Shabaab’s governance surpasses that of the federal government in most of its territory, at least in the domains of law and order and fiscal management (Panel of Experts report to the Security Council of 28 Sept 2021).

The problem for Al Shabaab is that its rule is only grudgingly accepted by the populations it controls and is resisted among the rest of the Somalis. Somalis massively would prefer to live under a modern, well-functioning state, and generally accept the blueprint of the liberal democratic state (which is, anyhow, the only solution on offer in this world). A democratic process that reflects the wishes of the population would therefore certainly lead to the construction of such a state.

It would be difficult for Al Shabaab and other anti-Western Somali forces to legitimately resist local community elections, especially if these can be held according to the traditional, consensus-based Somali culture rather than the destabilising result of ‘winner-takes-all’ majority elections held by secret ballot. The international supporters of Somalia should accept this variant of democracy and realise that such a state-building process may take much longer but will lead to a more stable result.

The current crisis may provide a good opportunity for the international community to re-establish an alliance with the Somali people – after all we share the desire for peace, stability, development, prosperity, and good relations. A short-term solution to the current crisis by a re-establishment of the elite pact among the political class, on the basis of the September 2020 accord, must be accompanied by a long-term commitment to the establishment of a democratic Somalia, preferably rooted in Somali political culture.