This was my submission to an ‘Ideas Festival’ organized by the Full Circle in Brussels from 2-4 December 2022

The human species is like an organism in which each individual is a node connected in dynamic ways to other individual nodes. Like the cells in a body, together we form a super-organism: humanity.

We may wonder whether Agent Smith in the Matrix was right when he characterizes humanity as a cancer exhausting and ultimately destroying its natural environment.

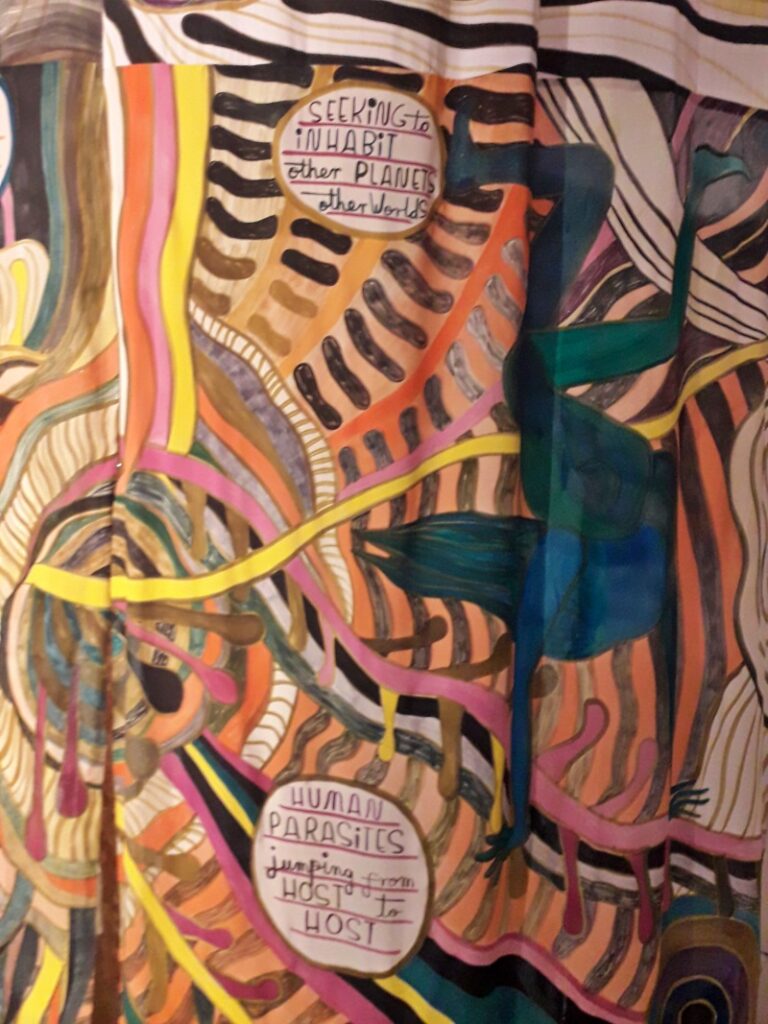

As Emma Talbot puts it in her giant drawing on textile exhibited in the 2022 Venice Biennale, is the current search for other inhabitable planets similar to that of parasites seeking new hosts?

Or can we do better than that?

A new vision of humanity is required. We have long seen ourselves as members of groups that compete with each other: nation-states, urban tribes, companies or institutions, social classes, clans… These groups are organized hierarchically, and their leaders benefit from this vision of the world as it helps to keep them in power. The model for this organization is the tree. From its central (institutional) trunk spring forth the branches that support positions of power, while the roots of the tree (civil society) dig into the earth, providing the tree with stability and nutrients.

Humans have always been fascinated by trees, from the Norse Yggdrasil to the Bodhi Tree under which Buddha taught. But in modern times we have come to misunderstand them. In modern forestry, trees are no more than resources exploitable by Man, and they are seen as individuals that compete among each other for sunlight, water and mineral resources. The ‘anarchic’ and supposedly inefficient primal forests have been clear-cut and replaced by plantations of trees planted at rational distances to each other so that they grow as fast as possible, protected from competitors and ‘pests’ by liberally applied poisons. The analogy with a perfectly regimented society is obvious.

In recent decades, ancient holistic views of trees have made a comeback through scientific progress. Now we understand that all trees in a forest are connected through the mycelium, fungal threads that transmit resources, energy and even information between trees, other plants and mushrooms. The forest is a super-organism that regulates itself much more intelligently than humans could ever do. Moreover, while modern forestry emits more carbon dioxide than the trees it depends on can absorb, and pesticides and herbicides kill life around trees, natural forests are essential both for biodiversity and as carbon sinks. So let’s turn to the natural forest for inspiration.

The model for the mycelium, and more generally for the forest as ecosystem, is the rhizome. A rhizome has neither centre nor hierarchy: each node can be taken as its centre. It can grow indefinitely, and it adapts to its environment as it grows – it is therefore heterogeneous, and it can survive indefinitely. When all the trees of a forest perish in a fire, it lives on in the rhizome and can be regenerated from it. Deleuze and Guattari in 1976 argued that the rhizome as structure is the opposite of the tree, which is homogeneous, centred, limited and hierarchical. The State and all other human institutions, they argue, are modeled on the tree. A contemporary human-made manifestation of the rhizome is the world wide web. It connects potentially all human beings in a vast network without hierarchy, where each node/person is fundamentally equal and the centre of its own constellation of connections.

Now, what if we humans could switch our vision away from the ‘forest of states’ or, in economic terms, the jungle of companies that are all in competition with each other, to the ecologically more accurate vision of humanity as one vast rhizome? What would this kind of post-state and post-capitalist society look like?

I imagine a world in which each person, like a tree, is sovereign. Through its roots it connects to the human rhizome: first to family, home community and networks of friends and acquaintances; but, within less than six connections, all humanity is reached. Our collective decision-making structures, through which we aim to survive and nurture life on Earth while creating the best conditions for each of us (and for future generations) stand not above us, as structures of authority, but sit below us, as infrastructure.

The Earth and its resources cannot belong to anyone, but are used collectively, by our species and others. Humans have not made them and can claim no property rights. Together, we can decide to stop running around frantically burning precious fossil fuels. We can slow down drastically, as during the first coronavirus lockdown, and use our free time to meet each other and start making plans for the future. Regenerative agriculture can easily feed all people on earth. It will take a few decades to clean up the mess we created, sort out all the rubbish, recycle everything we can, and detoxify rivers, fields and oceans. Then, gradually, the Earth can be transformed into a garden with many wild patches, where nature does its own thing.

Humanity has developed fantastically, but also a bit stupidly, in a material sense; now it is time to start developing spiritually. At both the individual and the collective level. Individually, each human is a universe in itself, that can be explored endlessly, with unknown potential. Self-knowledge should be a life objective for each person. Collectively, too, we urgently need spiritual development. Humanity is probably still in its early youth; in that case we can assume that it understands nearly nothing about itself or the world it lives in. A lot of ancient knowledge has been trampled in our rebellious teenager ‘know-it-all’ mood; this needs to be retrieved. We must be humble about our present levels of achievement and endeavour to learn more and to become more conscious. We have a long way to go, still.