The parliamentary and local council elections in Somaliland on May 31 went well; they were peaceful and they delivered a surprising result, because the opposition parties won.

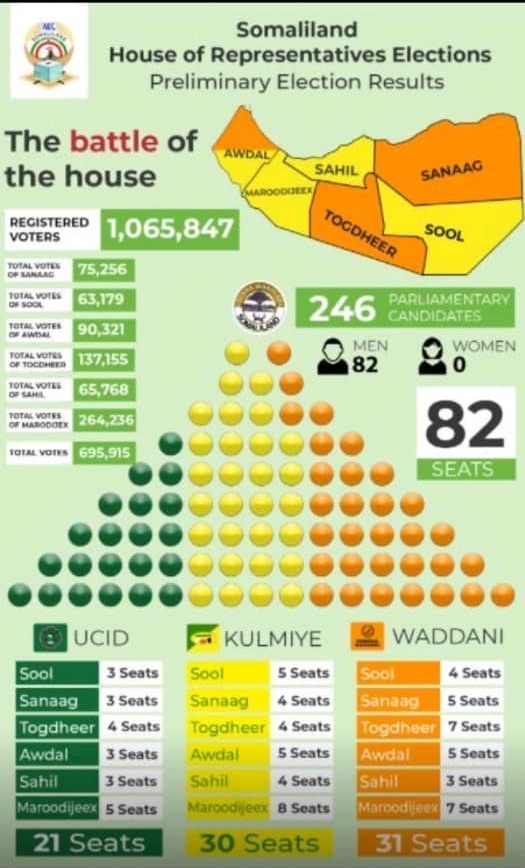

The ruling party, Kulmiye, came second nationwide in the parliamentary polls, preceded with just one seat by Waddani. UCID, a party which had been doing quite poorly in recent elections, made a surprising comeback.

It is too early to provide a proper analysis of the election results. What follows are some first thoughts. For those who want to understand more about the identity of these parties and the electoral system, I have added a slightly updated version of my doctoral thesis section on Somaliland elections and multi-party politics below these first reflections.

- These were the second parliamentary elections ever held in Somaliland; the previous elections were in 2005. They had been contested by different parties, and over the past 16 years some of the MPs had died, leaving their seats to their progeny. Before 2005, the parliament had been appointed during the Somaliland state formation process, in a manner similar to the system used in Federal Somalia today (with clan elders, together with current political office holders, selecting the MPs).

- It was understood that Somaliland’s President, Muse Bihi, was under pressure to hold long-delayed elections. In 2022 the renewal of the three-party system was scheduled to take place (see below); but by holding these important elections before that renewal, he has guaranteed the three currently existing parties will stay in power. This was considered by local analysts as part of a power-sharing deal: Kulmiye would consolidate its hold on power while the opposition parties, discredited among the electorate for their lack of opposition politics, would maintain their share of power at the local and national level.

- Kulmiye, the ruling party, was thus expected to win. Besides strongman tactics during the electoral campaign (arrest and intimidation of opposition candidates and their constituencies, unequal access to media etc) the party attempted to buy the allegiance of clan elders with cash and political favours, as has become usual in Somali politics. The opposition parties, with much less to offer, appealed to the youth and people against the political system. That they won may signal that Somaliland’s electorate is gradually moving beyond clan politics, and people – especially youth – are voting for their preferred candidate, rather than the candidate their lineage leaders tell them to vote for.

- An example of this was the victory of the opposition candidate Barkhad ‘Batuun’, belonging to a minority that is discriminated against, the ‘Gabooye’. Being young, one of the first persons of this minority to complete university education, and from the opposition, this candidate best represented change in the system. He won with more votes than any other candidate (more than 21,000 votes).

- However, not one of the thirteen female parliamentary candidates was elected, indicating that in this regard, Somaliland’s electorate has not yet matured. The main reason against voting for a female candidate is that her clan loyalty is in doubt, as it is divided between the lineages of her husband and of her father (exogamy being the norm).

- In Eastern Sanaag province, the non-participation of the large Warsangeli clan indicates they have turned their backs toward Somaliland and are more interested in joining Puntland; this may spell conflict for the coming years, especially in case President Bihi wants to burnish his nationalist strongman credentials.

- The two opposition parties have announced they will form a voting bloc in parliament, but given the apolitical character of Somaliland’s party politics, it is not yet clear what that voting bloc will stand for, besides more appointments for opposition candidates.

This is a quick, off-the-cuff analysis with insufficient data and input by local sources. I will update it as new insights emerge. My thanks to my friends in Somaliland who have helped me in this analysis, and congratulations to all Somalilanders for these peaceful and exciting elections.

Extract from draft thesis Robert Kluijver for Sciences Po:

International Statebuilding Intervention in Somalia.

From chapter 3: Self-driven state formation in Somaliland

3.3.2 Multiparty democracy

The Hargeysa Conference (1996-97) established the principle of multi-party democracy with the express aim of overcoming clan-based politics. To avoid the fragmentation of the political field into clan-based parties, a system was adopted in which the three biggest ‘political associations’ to come out of the first local council elections would be the only ones authorised to participate in political life during the following decade1. After ten years, local-council election results would designate the three political parties of the next decade, and so every ten years the existing parties have to contend with new formations to participate in politics. It is an ingenious system, but it sets the bar high for new entrants to the field. A political association has to pay a registration fee of 25,000 USD2 and demonstrate it has at least 1,000 members in each of Somaliland’s six regions. To qualify as a party, it has to obtain at least 20% of the vote in four of these regions3. If it fails, it has to wait ten years for the next chance, and it is not allow to participate in politics in the meanwhile – so it disbands. This procedure provides stability to the political system and forces political actors to reach across clan boundaries to establish electoral alliances. The objective was to keep clans represented in the House of Elders, and modern political forces in the House of Representatives.

Multi-party democracy did not come naturally. One study showed that many members of the public, especially from the periphery, had misgivings about the wisdom of the transition from consensus-based stability to majority rule of one party4. The experience of multi-party democracy in the 1960s had not been positive, and Cigaal had played a part in the debacle of the parliamentary period, leading to Barre’s 1969 coup. But other studies showed that Somalilanders mistrusted efforts by traditional leaders to hang on to power and felt the government needed more authority to develop the country5. Elections were a way to strengthen the state and modernise society.

Since the first elections, civil-society groups and political associations have tried repeatedly to establish non-clan-based alliances, but with each passing election hopes dwindle6. One such attempt was the Xaqsoor platform that participated in the 2012 elections. Admittedly, non-clan-based political movements often are dominated by certain lineages and offer little detail in terms of political programmes, which contributes to discrediting them7. But the rules of the electoral contest, coupled with eagerness to have access to power, encourage people to vote for those who ‘can deliver’, which are lineage members with a strong local position, preferably with good relations in Hargeysa. Thus a clear effort to overcome clan-based politics and supplant it with modern political identities through a system of multi-party democracy was thus defeated by… clan-based politics.

The belief that multi-party politics would thus inaugurate a new, non-clan based political era was rapidly abandoned by the political class. For example, the 2002 local council elections were held with closed lists: the political parties that aspired to become a party decided on its representatives in each electoral district, and people voted for the party, not for individual candidates. This might have encouraged non-clan based voting, were it not that the three political parties were, at the top, already clearly clan alliances; and it allowed the members of the political class to remain in power by fielding their own candidates. This dissatisfied local electorates, who desired more control over who their representatives would be, so since the 2012 elections open lists have been adopted, but the results are divisive. As one interviewee in Berbera noted, “each lineage tries to field its own candidate. A place on the local council is seen as a sure source of income for the lineage. There is no agreement on the common good for the town, the district or the country this way.8” Furthermore, the candidates from strong lineages that stand a good chance of being elected can sell themselves to the political parties. This encourages corruption (see section on fraud below). List-switching became a common occurrence in 20129.

The capture by clan of the multi-party system seems to result in a certain balance at the national level, where most Isaaq and some Gadabuursi lineages are represented, and even some other clans of Somaliland, but at the local level it is experienced as destabilising. As the same interviewee in Berbera noted, “Identity politics have penetrated into the household level. Many marriages are cross-clan, and elections now disrupt these. Elections have driven up the divorce rate as the constant social media bombardment is causing high tensions in such cross-clan households, as the husband and the wife will have different information flows on their clan-dominated social media channels – each lineage has its own WhatsApp group – and they may fight for the loyalty of their children.“

To give a measure of the competition: in the 2012 local council elections seven political associations fielded candidates, in total 2368 candidates for 379 seats (13 to 25 seats/council for 23 local councils). Parties had no control over which candidates were fielded10; they were usually suggested by local forces based on their capacity to mobilise voters along clan lines.

Accordingly, there is no loyalty to political parties. If an influential clan member leaves his party to join another – a common occurrence – his constituency will migrate with him. This happened when Cirro and many other Habar Yoonis MPs left UCID to join Waddani before the 2012 elections11. This explains why, at first sight, political parties do not seem to be clan-dominated; allegiance to a political party does not occur at the clan level, but at the lineage level.

| 2017 elections12 | Kulmiye | Waddani | UCID | none |

| Habar Yoonis | 10% | 80% | 5% | 5% |

| Sacaad Muuse | 80% | 10% | 5% | 5% |

| Issa Muuse | 60% | 25% | 10% | 5% |

| Habar Jeclo | 70% | 20% | 5% | 5% |

| Ciidagale | 20% | 25% | 50% | 5% |

| Carab | 50% | 40% | 5% | 5% |

| Dhulbahante | 20% | 30% | 20% | 30% |

| Warsangeli | 30% | 20% | 5% | 45% |

| Gadabuursi | 45% | 50% | 0% | 5% |

| Ciise | 30% | 30% | 0% | 40% |

Tables 4 and 5: Clan voting by political party in 2005 and 2017

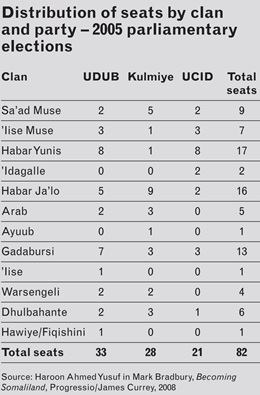

From these tables it emerges that most Sacaad Muuse and Habar Jeclo voted for Kulmiye in 2005 and 2017; the Habar Yoonis massively backed Waddani in 2017, and the Ciidagale usually vote for UCID. But otherwise clan votes are spread among all the parties. It is only when one inspects politics at the lineage level that the clan infiltration of the parties becomes clear.

Somaliland’s parties function more like umbrella organisations, federating the pro-government lineages on one side and anti-government lineages on the other, than like political parties in the West. In fact, parties avoid taking strong political stances on issues as doing so might scare away voters13. The only party that famously came with a specific idea for social development was UCID, who suggested to introduce the welfare state to Somaliland14. The political field is not a space for competing ideas but for competing interests15. The presence of diaspora returnees (approximately half of the representatives elected in 2005 had a diaspora background16) has not changed this.

Three more points can be made about the effects of the multi-party system on state/society relations. The first is that it has reinforced centralisation. To stay relevant, political parties and their members must participate in the daily politics of the capital city. This brings them closer to the urban state elites than to their local constituencies. This is of course a problem in most centralised parliamentary systems. Electoral democracy is strongly supported by the urban-based educated class and the diaspora, but it was never a loud demand of Somaliland’s rural population and lineage elders. “There was a debate on television about this” remarked an observer17. “People were asked what they thought about their parliamentarians. About 99% [sic] of the people said they were unhappy because their MPs never visit them. But MPs receive no financial support which would enable them to do this. When they do go back, constituents ask for money and they do not have sufficient funds to be able to support everyone“. This quote tellingly describes what people expect from their politicians in the capital.

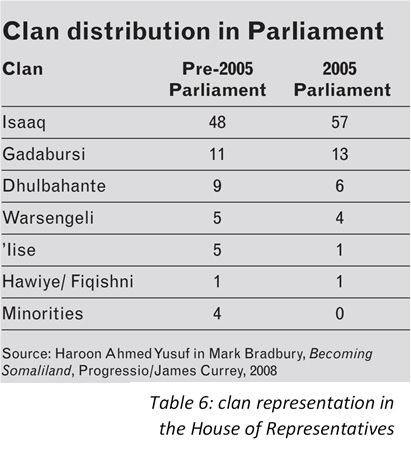

Second, the direct parliamentary and presidential elections introduced with the constitution of 2000 reduced the political participation of non-Isaaq and minority clans, confirming their misgivings about the transition away from nationwide consensus-seeking politics18. In the parliament elected in Hargeysa, 1997, the share held by representatives from the heartland (Isaaq & Gadabuursi) was 71%; in the parliament resulting from the 2005 elections, this share jumped to 85%. None of the minority candidates made it, the Ciise only obtained one seat19, and Harti representatives decreased from 14 to 10. Hidden behind the overall figure of the Isaaq gain of seats is the decline, in terms of representation, of all smaller Isaaq clans (Ciidagale, Carab, Cimraan, Ayuub, Toljecle), who lost 13 of their 21 seats in parliament; they were all won by the big clans (Habar Yoonis, Habar Awal and Habar Jeclo) that gained 23 seats collectively.20

Third, multiparty politics did little to further the position of women in society. As Cabdiraxmaan Ýusuf Duale ‘Boobe’ put it: “Women have been largely excluded from politics. One of the reasons relates to the clan system. Usually a woman is not seen as belonging to a clan. This is because in a way she belongs to two clans – she has her own clan and also the clan of her husband.21“. This has proved less of an obstacle in federal Somalia than in Somaliland. International pressure aside, it seems women in Mogadishu are more present in public life than in Hargeysa, pointing to a cultural factor: Northerners (pastoralists) are considered more socially conservative than Southerners (largely urban and agricultural).

Many commentators of Somaliland politics apply a formal analysis framework, where they examine the rules governing Somaliland’s state, note where those rules are deficient or not being followed, suggest fine-tuning the rules and appeal to authorities to stick to them, and encourage stakeholders to bear pressure on the authorities to do so. This method of analysis consists of negating the informal nature of Somaliland’s politics and the rhizomatic nature of the state-society nexus. It demands that all public relations be governed by formal law, reflecting what Bourdieu has called the victory of jurists over politicians in late 19th Century Europe. I do not believe this method of analysis is helpful. It is more useful to ask how society, in its rhizomatic state, interacts with and transforms the formal institutions of the modern state? Do these institutions in turn influence the development of society? What can we expect, in the medium and long term, from this interaction?

Two areas of unfolding state-society relations can clarify these questions: elections–the essential legitimation process for the state–and peace & security – what society expects from the state.

3.3.3 Elections

| Year | Due | Held | Results |

| 2000 | Constitution | ||

| 2001 | Constitution | 1,187,000 votes cast: 97% Approval | |

| 2002 | Local council Presidential | Local Council | 440,000 votes cast; 18/23 local councils elected. UDUB, Kulmiye and UCID selected as political parties. Two women elected. |

| 2003 | Parliament | Presidential | 489,000 votes cast. Acting president Kaahin (UDUB) re-elected with 42% with a narrow margin of only 80 votes |

| 2005 | Guurti | Parliament | 670,000 votes cast: 39% for governing party UDUB, 34% and 27 % for opposition parties Kulmiye and UCID |

| 2007 | Local Council | ||

| 2008 | Presidential | ||

| 2010 | Parliament | Presidential | 538,000 votes cast, Siilaanyo (Kulmiye) wins with a comfortable lead of 49.6 % over 33 % for Kaahin (UDUB) |

| 2012 | Local Council | Local Council | 811,000 votes cast; 19/23 local councils elected. Kulmiye, Waddani and UCID selected as political parties. 379 available seats, 10 women elected |

| 2015 | Presidential Parliament | ||

| 2017 | Local Council | Presidential | 566,000 votes cast, Muuse Biixi (Kulmiye) wins the election with 52 % over runner-up Cirro (Waddani), 29% |

| 2020 | Lower House | On 12 July 2020 the political parties agreed to schedule lower house and local council elections for late 2020 | |

| 2021 | Local Council Parliament | 695,915 votes cast on 1,065,847 registered voters (65%); Waddani 31 seats, Kulmiye 30 seats, UCID 21 seats. No women elected | |

| 2022 | Presidential |

From the table above, it appears that Somaliland’s electoral democracy is far from perfect. In fact, the percentage of cancelled or delayed elections surpasses that of federal Somalia. Of the thirteen elections that should have taken place, two were on time, six were delayed for a year or two (assuming the 2020 lower house elections will take place as planned in 2022), and five were never held. It has not even been decided yet how to hold elections to the Upper House of Parliament (Guurti). Moreover, the second decade was worse in terms of delayed and cancelled elections, showing a worrying trend. The reasons often heard for delays are lack of preparation, including the unresolved issue of voter registration; institutional difficulties, notably surrounding the National Electoral Commission; contextual factors such as drought; and, more informally, expenses.

As a local research centre in Hargeysa noted in early 2020: “Somaliland people elected 487 officials in public offices; all of them, except the president and his vice president, are in the office beyond their elected term. Only the President and his vice president have a legitimate term. Guurti members have been in office nearly 23 years, House of Representative members have been in office nearly 15 years and Local councillors have been in office nearly 7 years.22” A replacement mechanism for members of parliament who die in office has not been agreed on; in most cases the vacant seat of a deceased parliamentarian or Guurti member has been taken by his son23. The 2021 elections, however, brought an end to this odd situation for the Lower House, with the election of many young people and a victory for the opposition parties.

As long as no census is conducted in Somaliland–and as yet there are no plans for one–fully representative elections are not even conceivable. A census is the primary, fundamental element of state control over society. It cannot be replaced, as it now is, by asking lineage chiefs for population (clan) numbers. Exaggerating the strength of one’s clan is a long-standing tradition in Somali culture24.

Besides the absence of a census, elections have been riddled with manifold problems since 2002. Lack of capacity of the electoral commission, irregularities in voter registration, questions about the limits of electoral districts, use of government funds by the ruling party, lack of campaigning experience, few opportunities for women in politics, shortcomings in voter education, inexperience of the media, and widespread multiple and underage voting25 all contributed to making elections a messy and contentious process.

The National Electoral Commission was often criticized for election delays and other problems. But the 2016 voter registration campaign, using iris eye-scan technology, was considered a true improvement by the population and external observers26. The conduct of the 2017 and 2021 elections was also orderly and transparent. Voters participate enthusiastically in elections even though the opinion about the political class has grown increasingly negative27.

For many Somalilanders, the root problems during elections are Somaliland’s political parties. As we saw above, parties have become clan-alliance platforms, bringing together different lineages, expressly avoiding ideology or even policy suggestions to remain open to any possible ally. Political parties are machines to capture power and not much else. For example, they all fail to abide by their own charter, notably on the issue of internal democracy28. The party leaders seem immovable. Since becoming president, Muuse Biixi has not stepped down as leader of the Kulmiye Party (against its statutes) and eliminated contenders from within the party. This means that there are few chances for renewal in the parties, and it is difficult to establish new ones29.

Here is an example of how the rhizomatic nature of Somaliland’s politics at once uses and violates formal organisation; it uses it to stay in power while violating the rules, allowing a handful of people to dominate the political scene over decades without scope for renewal. The same applies to the Guurti. In the informal clan system, elders are appointed to mediate in a certain conflict, without obtaining an institutional position or its advantages. Renewal in such a system is constant and natural, depending on the capacity of the elder to mediate effectively.

Politicians contest elections bitterly but maintain cordial relations the rest of the time30. Cabduraxmaan Cirro was close to calling on his supporters to not accept the election results in 2017, which could have led to a bloodbath (three people died in the riots provoked by the announcement of his defeat). He finally decided to accept mediation attempts first, and later to respect the official tally; but Cirro has always been a loyal member of the parliament, rarely opposing the government or formulating alternative policies. State elites in Somaliland, including opposition politicians, show remarkable political class solidarity.

It is not lost on the electorate that whoever they vote into power is likely to move to Hargeysa, become a member of the state elite and enrich himself. For his constituency, that behaviour is not seen as negative if he remains loyal, representing their interests too. Hoehne, speaking to Warsangeli citizens in Sanaag, was told that politicians that moved to Hargeysa were seen as ‘lost sons’31, but that may be because the Warsangeli are distant from Somaliland’s heartland, and are becoming alienated from Somaliland’s politics and economy. While Warsangeli businessmen used to have a stake in the port of Berbera, they are now increasingly turned toward the much closer port of Bosaso, and Puntland’s politics where they have a stronger representation. In the 2021 local council and parliamentary elections, the Warsangeli did not participate at all.

Fraud has been a feature of all Somaliland’s elections, but as the stakes are rising, its scale is increasing. Fraud observed in Somaliland includes direct payments to voters on the eve of elections, buying unused ballot papers from station managers and filling them (mostly in remote places), paying campaigners or other groups to vote multiple times in different stations or paying local organisers to deliver votes. The latter practice may approach ‘normal tradition’, where candidates offer feasts, qat and gifts to local authorities to secure the vote of their subjects32. It may even be argued that direct returns to voters or local authorities are the only manner in some African societies to honour a politician’s sense of obligation to his constituency33; this is how some voters in Somaliland see it34. However this may be, vote-buying increases corruption and diminishes accountability. By buying votes, a MP frees him/herself of obligations to the community – after all, they have already been paid – and has good reasons to engage in self-enrichment, to recoup the losses made while campaigning or to fund the next campaign.

As the authors of one report candidly note, the “increasing monetisation of elections (…) risks tarnishing Somaliland’s enviable democratic record (…) and suggests that some may resort to malpractices in public office to recoup their investments.” It may be noted that the international community funds many if not most of the institutional election expenses (see below), thus making available more funds for campaigns. The funds spent by candidates during elections are staggering. One observer notes: “There is no trace of the money spent by everyone, including the government, donors, candidates, parties and people. It has damaged the democratisation processes and culture. It corrupted people … Even those who do not chew qat, started chewing because it was provided freely35.”

Civil society, which often embodies the hope of external donors that state-society relations will improve, is increasingly involved in the elections; this occurs through advocacy, awareness-rising and training, elections, and attempts to mediate potential conflict. Such activists and their organisations retain a formal independence from the state, but this does not mean that they are not integrated into the networks of power, especially when they are based in the capital. As with NGOs, their closeness to international donors and their direct relations with people in the government convince other Somalilanders that these organisations are part of the state elites and take part in the election bonanza.

One could see elections as a new ritual binding state and society in Somaliland together in some kind of feast: a few weeks where gifts are showered by the powerful on their constituencies and resources unreasonably wasted. Election day is a great celebration of nationhood: voting may not be very useful, but it is fun to participate. The electoral process leads to reconfigurations of power that obeys an unseen rhizomatic logic rather than the rules of the formal institutions of electoral democracy, which are not internalised even by the state elites. The real rules of the political game are that a) you keep the connection open to your lineage members, always ready to help; and b) you integrate Somaliland’s state elite (or political class), demonstrating loyalty to its values36.

If that is what elections signify in Somaliland’s context, then the international insistence on formal aspects of the electoral process are misguided. Among external observers and academics, there is a ‘democratic elections’ fetish. The fact that a country can hold elections and that the incumbent president accepts his eventual defeat, making way for a new government, is taken as proof of progress and development. Even when such elections drain the national coffers and lead to conflict, even when the political renewal is but a facade, leaving society frustrated for true change. As long as the rules have been more or less followed, elections are seen as a success: ‘free and fair’.

The turnover of presidents in Somaliland, all four of whom have left office by regular means37, is commonly taken as evidence of a mature democracy. But it rather seems to be the result of a tacit agreement among state elites that each main group gets a turn in power38, obeying a logic more related to consensual self-governance than to elections. The competitive logic of elections goes against the principle of consensual power-sharing present in self-governance traditions, and as Somaliland’s state becomes more ‘mature’ there may be more irregular transitions of power.

This exclusive focus on formal processes explains why donors provide technical support and funding for election-related programs, whereas there was almost no support for the more than thirty local and national peace conferences that helped shape Somaliland in the 1990s39. Even the first round of elections (up to 2005) was hardly supported by the international community. The first serious involvement of international actors, in 2007-2008, to help the National Electoral Commission complete voter registration, contributed to a delay in the elections of two years40. EU countries provided about 75% of the election budget in 2010, and about 50% of the 2017 election. From their point of view, supporting the young country means supporting the institutions that can modernise society; what may be characterised as mimicry, they call ‘following best international practice’.

The excessive importance given by the international community to correct electoral processes is well understood by Somalilanders. It contributes to their pleasure in participating in this ritual. When I travelled from polling station to polling station through the Maroodi Jeex district on election day in 2017, I was continuously asked: “See? Isn’t this a good election? Are you going to recognise us now?”

While most of the population participates with passion and pleasure in elections, this does not mean that they have made a choice for multi-party electoral democracy over clan-based consensus politics. Both coexist. The informal sphere of consensus is needed to balance the dysfunctions of the formal sphere. The ‘winner takes all’ aspect of elections is mitigated by the rhizomatic power arrangements that take place under the surface, with the objective of preserving peace among the clans and within the state elites. But these arrangements do not seem to be able to absorb new social forces or generate new socio-economic policies, for example for better political inclusion of women and youth or employment-based economic diversification. The educated youth is massively migrating41. In the 2021 elections, the youth seems to have taken some kind of revenge. While the ruling Kulmiye party made efforts to rope in lineage elders, as usual, the opposition parties, which faced distinct disadvantages during the campaign (arrests, prohibitions, difficult access to the media, intimidation of their candidates and voters) appealed to the youth vote for change; the opposition parties won (see table above).

Elections are also criticised from within the state elites. “Elections have not helped Somaliland. We have adopted this system to gain international recognition, but has that helped? We go from one election to the next, they are costly and destabilising and do nothing to improve the situation in the country.”42 Both within and outside the state elites one hears voices regretting the consensus-based politics of which Borama was the high point. Some of my interviewees found, paradoxically, that mayors appointed by the central government functioned better than those elected by local councils; because the principle of self-interest prevails over the common good, thanks to the election, while a mayor appointed by the central government might act in pursuit of the common good43. The way elections have engendered large-scale and society-wide corruption is maybe the main criticism levelled against them.

Among educated Somali youth many see the shortcomings of the current electoral system, but none believe a return to clan-based self-governance is possible; electoral reform is the only way forward. In fact, both political systems coexist side by side, one in the formal, the other in the informal domain, both penetrated by the same rhizomatic social logic but with different expressions. Informal consensus-seeking politics are still common, as we shall now see in the domain of conflict prevention.

The entire chapter on Somaliland (a slightly older version) can be found on ResearchGate, here.

1 This system was copied from the 1960 pre-independence elections and had been devised by the British. Hansen & Bradbury 2007 “Somaliland: A New Democracy in the Horn of Africa?” p468.

2 This measure was introduced before the 2012 elections; see Haroon Ahmed Yusuf: “Representation” in Africa Research Institute (ARI) 2013:16

3 Dr Ali Yousuf Ahmed MP, Second Deputy Speaker of the House of RepresentativesinAfrica Research Institute ARI 2013:13

4 Jimcaale 2002 “Consolidation and Democratization of Government Institutions” Draft for APD; p28

5 APD 2000 “Rebuilding Somaliland” p35

6 Multiple interviews with young people that have participated in such non-clan political platforms

7 In the case of Xaqsoor, I could not find its political programme – beyond positions taken on its Facebook page – and I was told its members canvassed among Carab, Ciise and Dhulbahante voters to ensure representation in all regions.

8 Interview with Shacban Cilmi, secretary of the Berbera Economic Forum in May 2019.

9 Rift Valley Institute (RVI) 2015 “The Economics of Elections””.

10 Academy for Peace and Development & Interpeace (APD) 2015: “Somaliland’s Progress Toward Peace: Mapping the Community Perspective” p16.

11 The split occurred when Cirro, speaker of the House of Representatives and potentially commanding many more voters, insisted he should become the party leader, which Faisal Waraabe refused

12 Data estimated by author and revised with input from keen political observers in Somaliland; there is no polling information breakdown by clan available, so this table only presents an informed guess.

13 See the remarks about the first ever presidential candidate debate on TV by Hoehne, 2018:15.

14 Hansen & Bradbury 2007:466 note that UCID’s leader Faisal Waraabe and several of its founding members returned from Scandinavia. The proposal was greeted with derision, given Somaliland’s lack of resources to pay for such services.

15 See the remarks by Haroon Ahmed Yusuf, Deputy Director, Social Research and Development Institute, in Africa Research Institute (ARI) 2013:16. I have heard this point of view frequently in my interviews.

16 Haroon Ahmed Yusuf in ARI 2013:17.

17 Haroon Ahmed Yusuf in ARI 2013:15.

18 Hansen & Bradbury 2007:470.

19 The Academy for Peace and Development post-elections report of 2006 “A Vote for Peace” explains that the Ciise candidates feared that their clan-members would not turn up in sufficient numbers, and that four of the five candidates decided to withdraw from the process on the eve of the elections. Their seats were won by Gadabuursi and Isaaq representatives instead. APD 2006:47

20 All figures from APD 2006.

21 Africa Research Institute 2013:19

22 Centre for Policy Analysis Hargeysa (CPA Hargeysa) 2020: “Somaliland Local Councils: The Birthplace of Political Parties is a Crossroad” p6.

23 The practice was defended by an interviewee who reasoned that a position in parliament is an important source of income, and as the government offers no support to the families of deceased parliamentarians, it makes sense that a son takes his or her place to supplement for lost income.

24 Hoehne 2011: “No Easy Way Out: Traditional Authorities in Somaliland and the Limits of Hybrid Political Orders”

25 The domestic elections observation team Somaliland Non-State Actors Forum reported that ‘all polling stations experienced some multiple voting” during the 2012 local council elections (Saferworld 2013:12). The high number of votes cast in those elections was, according to all observers, mainly the result of multiple voting. See also Pegg & Walls 2018: “Back on Track? Somaliland after its 2017 Presidential Election” in African Affairs 117/467, 326-337; p327. Underage voting is also widely reported in each election.

26 See Pegg & Walls 2018:331

27 Abokor & Ali for Rift Valley Institute (RVI) 2018 “Assessing the 2017 Elections”: 71% of citizens said 2017 elections were ‘free and fair’, 23% noted fraud and vote-rigging. See also Hoehne 2018 about the post-elections situation.

28 Abokor & Ali 2018 10-12 and CPA Hargeysa 2020:12-15. The same complaints over the past two decades (cf Jimcaale 2002) point at the unwillingness of political parties to reform themselves.

29 CPA Hargeysa 2020:13

30 Abokor & Ali for RVI 2018:2

31 Hoehne for Rift Valley Institute 2015 “Between Somaliland and Puntland” p60

32 Verjee e.aet al. for Rift Valley Institute (RVI) 2015: “The Economics of Elections in Somaliland” p33-35

33 Vicente & Wantchekon, “Clientelism and Vote Buying: Lessons from Field Experiments in African Elections” in Oxford Review of Economic Policy 25/2 (2009): 292–305

34 “I voted for you – what do I get back?”. See the quote referenced in note 144

35 RVI 2015:37

36 These would include political values such as being against unity with the rest of Somalia and always eschewing violence in favour of peaceful, negotiated solutions to conflict; economic values such as participating in the race to get rich, accepting income inequality, living in a nice house and driving a big car (but not at the expense of helping your lineage); social values such as being down-to-earth, not too serious and enjoying a good qat chew with your friends. Of course, such values and their external manifestations change. Photos of the 1993 Borama conference show that all delegates were wearing traditional, simple garb, while nowadays a suit and tie is the dress code of public life for the elites. Flouting your wealth used to be frowned on but over the past decade it has become acceptable.

37 As defined by Posner & Young in “The institutionalization of political power in Africa” (in Journal of Democracy 18, 3, 2007, p128 quoted by Pegg & Walls 2018:328) regular means mean accepting one’s defeat, not representing oneself when not allowed, or dying a natural death while in office.

38 One of my interviewees (May 2019) believed that the next elections must be won by the Habar Yoonis; when they’vethey have had their turn in power, the terrain might be ready for a new type of non-clan-based politics.

39 Bradbury, Abokor & Yusuf 2003:466

40 The EU had agreed to support the voter registration process through the NGO Interpeace for the 2008 presidential election. The members of the National Electoral Commission and the leaders of the three parties opted for a technologically difficult biometric registration system. The international partners objected but, because of ‘national ownership’, agreed to support this process nonetheless. The result was so messy, with 1.4 million voters registered, that it became impossible to hold elections on that basis. The EU and Interpeace engaged in frantic shuttle diplomacy to resolve the crisis, but to no avail. After they withdrew their assistance, the political parties and the NEC opted for a simpler registration system and held the elections in 2010.

41 World Bank 2016: “Somaliland’s Private Sector at a Crossroads” notes that urban middle-class families in particular seek to prepare at least one son to find employment overseas to keep the remittances flowing. 40% of households in Somaliland receive on average 271 USD per month in remittances according to the report (p82)

42 Interview with Ibrahim Habane, ex-secretary of the Guurti, May 2019 in Hargeysa.

43 This was also the view of the ex-mayor of Burco, interviewed on 5 June 2019 in Burco.