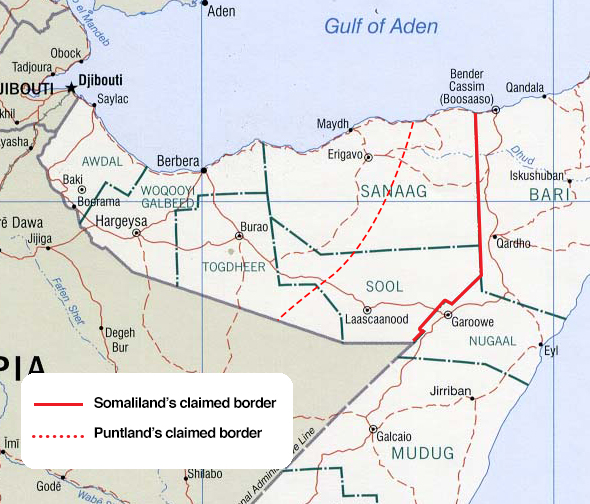

The formation of Puntland[1] in 1998 provided a ‘relevant other’ that was useful to strengthening Somaliland’s identity[2]. Puntland based itself not on the pre-civil war borders, but on ‘Hartinimo’, referring to the Harti clans belonging to the Darood clan family. Thus, Puntland claims that all the Dhulbahante and Warsangeli living in Somaliland belong to Puntland as per the map below.

‘Harti’ is a forefather common to the Majerteen, the Dhulbahante, the Warsangeli and smaller clans such as the Dashiishe. The common ancestor had been largely forgotten given the political strength of the Majerteen lineage and the concept of Hartinimo only gained currency when the Majerteen minority in Kismayo invoked it in 1992, seeking support against the Darood from the Ogaden branch who ousted them in a bout of ferocious clan fighting[3]. In the mid-1990s, when Col Abdullahi Yusuf was fighting General Abshir over the leadership of the SSDF and the Majerteen, Yusuf used the concept to gain the support of the Dhulbahante and Warsangeli; this broke the deadlock and led to the creation of Puntland[4]. Hartinimo is an imagined community based on an invented tradition, responding to a political emergency.

Puntland refers to the contested borderlands as Sool, Sanaag iyo Cayn. Cayn refers to the districts of Buuhoodle and Caynabo, the former inhabited by Dhulbahante, the latter claimed by them. Puntland’s border claims are vague, because they are based not on territory but on a nomadic people; at times they stretch to the maximum historic range of grazing lands used by the Dhulbahante and Warsangeli; at others they are limited to the population centres with a majority of Harti inhabitants, although for a lack of census there is no clarity on that point either. Somaliland bases its territorial claims on the historic border of British-administered Somaliland, which was also border between regions in the post-independence administration. But that border was based on the Majerteen sultanate, so it was already clan-based and defined by the Majerteen, with the difference that at the time the Majerteen wished to exclude the Dhulbahante and Warsangeli; the rival Warsangeli sultanate was loosely allied to Great Britain, and thus became part of British Somaliland.

The contested borderlands between Puntland and Somaliland moved from grey zone to war zone only in 2002[5], when Somaliland prepared general elections, and Puntland interdicted voting in Sool, Sanaag and Cayn[6]. A campaign visit by acting President of Somaliland Riyale to Laas Caanood on December 7, 2002 sparked an armed confrontation between militia loyal to Puntland and his escort. Later both sides withdrew to garrisons several tens of kilometres away from Laas Caanood to control the road from that town to their capitals. A year later, in December 2003, Puntland intervened in clan conflict among Dhulbahante in Laas Caanood, and kept its soldiers garrisoned there. The situation stayed like this until 2007.

Puntland’s president Abdullahi Yusuf was elected head of the Transitional Federal Government in Nairobi, 2004. As President of the federal government Yusuf took an even harder line against Somaliland’s secession, and on 29 September 2004 both armies clashed again West of Laas Caanood. Then, with the election of Maxamuud Muuse Xirsi (Cadde Muuse) as president of Puntland in 2005, interest in Sool waned; Puntland’s armed forces were required for the fight against the Islamic Courts Union and other contenders. The conflict with Somaliland stagnated until 2007, when the army of Somaliland took over Laas Caanood without resistance. They were apparently supported by Ethiopia, who feared ONLF infiltration in Sool[7].

People living in the contested borderlands were, in fact, neglected by both administrations that claimed them, and so they distanced themselves from both to set up autonomous clan administrations[8]. This led to Maakhir, an independent state of the Warsangeli between 2007 and 2009[9], and to two movements among the Dhulbahante: Sool, Sanaag and Cayn (dubbed ‘SSC’, 2009-2011) and Khatumo (2012-2018). One of the reasons for the formation of these states was an attempt to directly access international aid, as the rival claims by Somaliland and Puntland impeded the operation of UN agencies and most NGOs in the area[10]. However, none of these attempts at autonomy proved successful. Besides some diaspora funding the ‘autonomous administrations’ had no resources to provide any services to the population and aid agencies still avoided the area.

Diaspora funding often stokes divisions between the sub-clans and with both neighbouring states[11], as identities harden in the situation of ‘long distance nationalism’[12]. A large part of diaspora funding goes to arming factions and supporting public relations activities. Comparatively little diaspora funding was invested at that time in education, health or infrastructure[13].

From late 2009 onward, a series of assassinations of members of Somaliland’s administration in Laas Caanood and its Dhulbahante supporters took place, as well as a few IED attacks, in what seems to have been an attempt by Al Shabaab to establish itself in the region[14]. Somaliland’s presence in Sool diminished and the region remained beset by clan conflict among the Dhulbahante.

When in 2010 Siilaanyo became president of Somalia, he claimed he could solve the conflict on the basis of his better understanding of the Dhulbahante, hailing from the Habar Jeclo/Maxamed Abokor/Aadan Madobe lineage from the Hawd. But an overture after his election resulted in a snub, and armed conflict continued in the region, with occasional intervention from Puntland on the side of the Dhulbahante.

Khatumo was founded under a giant tree on the outskirts of Taleex in January 2012. With the election of Hassan Sheikh Mohamud in Mogadishu later that year, Dhulbahante elders and political representatives hoped that the new federal government would support their autonomy and recognise Khatumo as one of the federal member states. Those hopes soon vanished, and Dhulbahante MPs pushing for recognition were told to deal with Puntland instead[15]. But Puntland was as hostile to the Dhulbahante ‘secession’ as Somaliland was. Khatumo captured Tukaraq border post from Puntland in early 2012 in one of its first feat of arms. In June 2012, Somaliland dislodged Khatumo from Tukaraq and then withdrew, allowing Puntland to take it back. This incident convinced Dhulbahante that both neighbours were cooperating against their autonomy.

Between 2012 and 2017 Khatumo was involved in about 80 armed clashes, almost all of them with Somaliland armed forces, with peaks in 2014 and 2016; in most of these clashes there were no casualties, so the war seems to have been more about posturing and intimidating than trying to defeat the other. There was little evolution of the conflict and, under pressure from local elders, Khatumo and Somaliland decided to talk and reach an agreement. This prompted a scission in Khatumo, with its vice-president creating a new faction opposed to Somaliland, that continues to create an occasional disturbance.

In 2017 President Siilaanyo and the President of Khatumo state, Cali Khalif Galaydh (2014-2017) reached an agreement and the Khatumo state dissolved[16]. The agreement included the integration of Khatumo’s forces (actually these were clan militia loosely bound to the Khatumo leadership) into Somaliland’s army, a better representation of Dhulbahante in Somaliland’s state structures and the extension of development support and the rule of law to Dhulbahante areas. The current administration of President Muuse Biixi however does not seem interested in honouring the agreement[17] and while Khatumo seems to be ‘dead’, the underlying conflicts have not been solved.

Fighting that erupted in May 2018 between Puntland and Somaliland near Tukaraq, which has been Puntland’s border post inside Sool, was of a novel character, as it was initiated by both armies, not clans. Past conflict occurred between neighbouring clans or sub-clans whose alliances with either Puntland or Somaliland were not steadfast and did not lead to significant support from these governments. By themselves, local clans have insufficient resources for protracted warfare. They also avoid fatalities, which lead to either revenge killings or onerous blood-money compensation. This moderating factor is now absent. It is now the army of Puntland fighting against that of Somaliland.[18] The confrontation between both armies led to more than 75 fatalities[19], the bloodiest armed clash in the history of both countries.

This conflict was subdued by intense shuttle diplomacy of the UN, probable pressure by Ethiopia on both sides[20], and the appeals of other diplomats. Mogadishu had no appetite to be dragged into an armed conflict with Somaliland by Puntland. At the time of writing the conflict remains unresolved, with both armies in a stand-off along a road on which normal traffic has resumed[21]. Indeed, cargo including cattle, construction materials, fresh and dry foodstuffs is transported over this route, and Somalilanders who need a Somali passport still travel to Garowe to obtain one.

A year after the fighting east of Laas Caanood, a military build-up took place around the town of Yube, between Badhan and Ceerigaabo. Again, Somaliland took the initiative, setting up a base near Yube in March 2019[22]. Over the following months, a few clashes took place and several military commanders defected with their units to Puntland; so did Somaliland’s governor in Badhan. His replacement was chased out of the town of Hadaaftimo (the historic seat of the Warsangeli sultan). Thus, Somaliland ‘lost’ the Warsangeli areas by trying to exert fuller control over them.

This was the first time that tensions arose simultaneously in Warsangeli and Dhulbahante areas, denoting the political rather than the clan nature of the current conflict. One could tentatively conclude that when Somaliland tries to function like a state, willing to upset clan sensitivities and imposing its ‘monopoly of violence’, it fails. In contrast, when Somaliland’s government negotiated with the Warsangeli elders to curtail piracy, relations seemed good and the desired results were obtained.

One cannot understand the dynamics of the conflict in the contested borderlands between Somaliland, Puntland and local forces pursuing autonomy without referring to inter- and intra-clan fighting among the Dhulbahante[23]. These conflicts often centre on land issues, notably access to pastures, wells and water reservoirs but are also sparked by commercial conflict (e.g. turf wars between qat dealers or competition over NGO contracts) or personal affairs (insults or marital problems involving different lineages). Often one will find several of these causes intertwined. When a conflict is not properly solved it can generate a feud, and some feuds have been going on for so long that they have resulted in general hostility between two population groups; at a large scale (e.g. Majerteen vs. Isaaq) or a small one (e.g. Samakaab Cali vs Faraax Cali in Taleex, both lineages of the Nuur Axmed sub-clan of the Dhulbahante/Maxamud Garaad)[24]. These recurrent conflicts are the most intractable and need the involvement of higher instances to be solved. Somaliland and Puntland have tried to play that role of peacemakers, but in practice they usually have become involved on one side of the conflict through influential clan members in their administration.

For example, Puntland’s vice-presidency is reserved for a Dhulbahante clan member. From 2009 to 2014 that was Abdisamad Ali Shire from the Samakaab Ali lineage in Taleex. He led an armed intervention against Khatumo state in Taleex in 2013. At one level, this may be seen as an action of Puntland (then preparing for elections) against the secessionist Khatumo movement. At another level, this was a local intervention to strengthen the Samakaab Cali against the Faraax Cali, who were siding more with Khatumo. The Samakaab Cali forces of Vice President Shire killed nine Faraax Cali clansmen, and this deadly tally still simmers on seven years later, despite many reconciliation efforts; the town of Taleex is still divided into two halves, with the Samakaab Cali on the East and the Faraax Cali on the West of that line. Political conflict is evanescent, and changes after elections, but clan conflict tends to be enduring.

When presidential candidate Abdiweli ‘Gaas’ and his Dhulbahante running mate Abdihakim Abdullahi Haji Omar, also known as ‘Amey’, won the elections in Puntland in 2014, the focus of the conflict shifted from Taleex to Buuhoodle, where Amey hails from. Indeed, most of the armed clashes between Khatumo and Somaliland’s army in 2015-2017 took place in the district of Buuhoodle. The fact that Somaliland’s Minister of Health from 2013 to 2017, Saleban Ciise Ahmed ‘Haglotosiye’, also hails from Buuhoodle, gave both Somaliland and Puntland strong leverage in this Faraax Garaad stronghold. Haglotosiye had joined the Somaliland government as one of the leaders of the SSC autonomous state.

The current VP of Puntland, Ahmed Elmi Osmaan ‘Karaash’, was born in Xudun. He was one of the three leaders of Khatumo State (2012-2014) before Galaydh took over. He had served as Minister of Aviation of Puntland between 2009 and 2011, became one of the leaders of Khatumo, fought Puntland’s forces led by fellow Dhulbahante VP ‘Shire’ as seen above, and then became Puntland’s Minister of Interior (2014-2017), before becoming Vice-President. His biography illustrates how individual Somali politicians cultivate and rely on their clan kin as base for their power, and then opportunistically navigate the corridors of power to gain influence for their lineage. When they fail, they risk losing ground to rival political entrepreneurs from the same lineage[25].

It may have been noted that while this section is about the contested borderlands between Somaliland and Puntland, the focus has been on the conflict among the Dhulbahante. The situation among the Warsangeli has been more peaceful. This is often attributed to the positive role played by their Sultan[26], who wishes to keep the peace with both sides, and is widely respected among the Warsangeli. He is the symbol of their unity, and actively promotes it, but refrains from participating in politics. Thus, in Badhan administrations by Somaliland and Puntland have lived side by side in cooperation, as they are both staffed by closely related Warsangeli lineages[27]. The loyalties of state officials and members of the armed forces are first to their lineage, and only in second place to their employer[28].

Nonetheless, tensions among Warsangeli have sometimes led to armed clashes with the involvement of both governments. The Dubeys, a small but influential Warsangeli lineage, has remained critical of Puntland’s efforts to integrate the Warsangeli populations as minor partners. They supported a local rebellion against Puntland in the Galgala mountains West of Bosaso and have not tried to expel the small but persistent insurgent group of Al Shabaab in the North East which ‘took over’ that rebellion in 2011-12. Yasin Kilwe, the leader of that insurgency, belongs to the Dubeys lineage. Al Shabaab directs its attacks mostly at Puntland’s Security Forces and Puntland’s government[29]. Somaliland has no military presence in Warsangeli areas, but the Warsangeli have well-organised security forces that cooperate with both Somaliland and Puntland (and who contain the threat Al Shabaab poses to them without apparently trying to remove it). Somaliland’s Minister of Defence from 2010 to 2017, was a Warsangeli. That Bixi has appointed an Ciise from Zeylac in his place may not help Somaliland’s war effort in East Sanaag[30].

Somalis also often insist that the Warsangeli are ‘even-tempered’ and business-like, unlike the ‘hot-headed’ Dhulbahante. This kind of cultural stereotypes may be insufficient, but they are used by Somalis to explain the different outcomes in the contested borderlands[31]. A more materialistic explanation would point out the Warsangelis have long had profitable business operations across the Gulf of Aden (they used to operate out of both ports of Berbera and Bosaso) and thus have more of an incentive to keep the peace; while the Dhulbahante, who rely almost solely on livestock production, are subjected to the vagaries of the market and the environment and the pressure of population growth, and thus more prone to internal conflict. As noted in chapter 3, the Warsangeli sultanate cooperated with the British empire, while many Dhulbahante fought it during the Dervish revolt. In any case, despite the similar situations in which both Harti clans find themselves, they have rarely cooperated over the past decades. This bears witness to the fact that ‘Harti’, as an invented or ‘remembered’ identity, is still quite weak.

What this case study reveals is that the states claiming control over Sool and Sanaag have insufficient means to back their claim; both the ‘land’ argument used by Somaliland and the ‘people’ argument used by Puntland are unconvincing. The harder each side pursues its claim, the more conflict. However, conflict is not primarily with the rival state, but with local forces that either claim self-determination, or demonstrate allegiance to the other state. Whether one of the claiming states pursues its claims or not is influenced by domestic political factors, mostly – such as elections.

Neither of these states has governed much in Sool and Sanaag, although Somaliland’s track record is better than that of Puntland, which seems to have invested nothing in these areas. In general, local communities self-govern, now as in the past. External support (NGOs, UN) is minimal, given the contested nature of the area. Efforts by the Warsangeli and Dhulbahante to formalise their de facto autonomy floundered on a lack of means and the combined hostility of Puntland and Somaliland.

The Dhulbahante are historically more divided, and prone to internal conflict, than the Warsangeli. The politicisation of these conflicts by the involvement of Puntland or Somaliland, who often come under the guise of ‘making peace’, usually aggravates the conflict, as each state tends to support one side in the conflict (the side with better representation in their government). Local actors opportunistically use their connections to one or the other side to press their advantage, while actors in the capitals of the claiming state use their position to extract material or political resources. Finally, involvement of Puntland or Somaliland tends to make local conflicts intractable, while clan conflict without external interference can usually be managed by local authorities, and is much less deadly.

[1] Warning: this is not a Puntland-centred analysis, because it was written as part of a chapter on Somaliland

[2] Hoehne 2011 “Not Born as a De Fact State“ pp. 324-325

[3] Hoehne 2011 p. 323

[4] Kluijver 2015 “Bosaso Area Study” p. 19

[5] Somaliland’s President Egal and Puntland’s president Abdullahi Yusuf had a working relation together and avoided conflict. There were no border controls and people and goods moved freely across the border until 2002.

[6] Cayn roughly encompasses the districts of Buuhoodle and Caynabo; the latter is terrain lost by the Dhulbahante to the Habar Jeclo armed by the British, took it over while fighting the Dervish revolt. Cayn means ‘well’.

[7] Hoehne 2015:66, based on several interviews with leading figures in the conflict.

[8] There had always been disagreement among the Dhulbahante on whether they supported Somaliland, Puntland or their own autonomy. Hoehne 2015 “Between Somaliland and Puntland: Contested Borderlands” pp. 78ff.

[9] In 2009 Warsangeli elders decided to support the new President of Puntland, Faroole, and ended the political experiment of Maakhir. The small but influential Warsangeli Dubeys sub-clan did not agree and later came to largely support the Galgala rebellion (Kluijver 2015:20).

[10]Markus Hoehne for the Rift Valley Institute 2015 : “Between Somaliland and Puntland. Marginalization, militarization and con?icting political visions” p. 78

[11] Hoehne 2015:73-74. Reporting on the more recent conflict between Puntland and Somaliland in 2018-19, Omar Mahmood of the Institute for Strategic Studies in Addis Ababa comes with a similar assessment in Mahmood 2019: “Overlapping claims by Somaliland and Puntland. The case of Sool and Sanaag” p. 15

[12] This term appears to come from Benedict Anderson. ‘The New World Disorder.’ New Left Review 193 (1992), pp. 3–13.

[13] In an interview with me in June 2019, Mohammed Hussein, Mayor of Burco in Siyad Barre’s time, and again from 1997-2000, told of his sustained efforts to convince the Burco diaspora to invest in development rather than in politics and conflict.

[14] Curiously, few of the assassins were ever identified, but there was some involvement of minorities originally from south-central Somalia living in the area: ex-Rahanweyn Resistance Army fighters who had fled to Sool and become craftsmen in the local market, and the Fiqishine, a small Hawiye/Habar Gedir settlement West of Laas Caanood. Al Shabaab involvement has never been proven but is all the more likely that at least one of the assassinations targeted an AS defector. Source: International NGO Safety Organisation Somalia database.

[15] Interview with Ali Khalif Galaydh, May 2019. He returned from the USA to become one of the Dhulbahante MPs in the federal parliament.

[16] The agreement between both leaders was helped by the fact they had been friends since attending Sheekh High School together in the 1950s. Interview with Ali Khalif Galaydh, May 2019.

[17] Ibidem

[18] Kluijver 2018 online: “Puntland and Somaliland sliding to war” on www.robertk.space. It must be noted that while Somaliland has a more regular army, Puntland relies mostly on clan forces over which it has little command. President Gaas complained that he had not known that the Qardho-based unit which led the deadly attack on Somaliland in May 2018 was planning an assault.

[19] Omar Mahmood, 2019:11, gives the figure of 200-300 deaths based on interviews with Puntland security forces. The number of 75 cited here was given by local sources and seems more reliable.

[20] It was rumoured that Ethiopia threatened both sides to stop its supply of munitions, of which it appears to be the main supplier (in contravention of the UN embargo).

[21] Personal communications with the International NGO Safety Organisation in Burco and Garowe, September 2019.

[22] This appears to have been a response to the defection of a Somaliland colonel (Habar Younes) to Puntland. Colonel Aare was opposed to the ‘Habar Awal-Habar Jeclo’ domination of Somaliland. It was rumoured (Mahmood 2019:) that Aare had returned to Sanaag with Puntland’s armed support to initiate an insurgency

[23] The two main groups in conflict are the Maxamud Garaad mostly residing in the Nugaal plain, physically and politically close to Puntland, and the Faraax Garaad of the Hawd plateau (which extends from Laas Caanood and around Buuhoodle into Ethiopia). The Faraax Garaad have more relations with Ethiopia and Somaliland (Jigjiga and Burco are their main trading centres) but generally have supported autonomy. Clashes between Somaliland’s armed forces and the SSC, and later Khatumo, usually have taken place in the Faraax Garaad area (south of Laas Caanood and around Buuhoodle).

[24] Taleex has symbolic significance because it was the seat of Sayyid Abdullah Hassan, the Dervish leader, and is still home to the imposing ruins of his fort and other structures

[25] Galaydh, the leader of Khatumo, told me he had ‘lost quite a lot of political capital’ among his people by negotiating the agreement with President Siilaanyo, as the deal failed to deliver the expected results.

[26] Siciid Sultan Abdisalaan has been Sultan of the Warsangeli since 1997.

[27] Observation of the author, who visited Badhan and spent time with both administrations discussing issues of cooperation in May 2017.

[28] Somaliland’s Chief of Staff reacted with relief when he learnt of the defection of some of his senior officers and their troops to Puntland, noting that they had never been loyal or advanced Somaliland’s interests, and now no longer needed to be paid. Interview reported by Omar Mahmood 2019:13.

[29] The conflict started when Puntland’s government gave a concession to an Australian mining company to prospect for gemstones in the Galgala mountains, where the Warsangeli/Dubey live, in 2005. Over the years what started as a local rebellion opportunistically morphed into a branch of Al Shabaab, who was initially receiving shipments of Eritrean weapons through Galgala (until 2011). The affiliation with Al Shabaab has strengthened since late 2015, when the Galgala insurgency split into a group supporting the Islamic State, mostly composed of Majerteen/Cali Saleban, and a more diverse group based in Dubeys territory remaining with Al Shabaab. As in Mogadishu, the leadership of Al Shabaab fights Islamic State actively. In January 2018 Al Shabaab overran the Puntland army base of Af Urur, but overall the conflict has remained a low-intensity one, resulting in about ten incidents (IEDs, assassinations, skirmishes) per year (source: INSO database).

[30] Interviews with two different analysts of Somaliland affairs, April 2020.

[31] This is also the argument made by Omar Mahmood, 2019:9.

[32] As heard by the author in discussions in rural areas of Somaliland. See also Mahmood 2019:19 “A common complaint was that politicians, especially those based outside Sool and Sanaag, carry little weight locally and are essentially figureheads. Clan members argued that this emphasis on the elite has been a misplaced attempt to garner and gauge clan support.”

[33] Mahmood 2019:19-20